The 1990s: The Rise of Institutional Investors and independent Boards

Lipton Reflects as Wachtell Lipton Reaches Silver Anniversary in 1990

In 1990, Wachtell Lipton celebrated its twenty-fifth birthday. By that time, the firm had grown to include nearly 50 partners and a similar number of associates. As the firm matured, Lipton and his early partners did their best to preserve its original culture of collegiality, friendship, and commitment to professional excellence. They led by example in treating the firm’s associates, paralegals, and support staff as part of a family that cared about each other.

Many of Wachtell Lipton’s competitor firms had undertaken massive expansion plans and created many new domestic and international offices. Lipton took a different approach. To maintain the firm’s intimate nature, Wachtell Lipton hewed to a single office. Substantively, Lipton believed that it was a strength, not a weakness, that Wachtell Lipton partnered regularly with leading firms in Delaware, Chicago, Los Angeles, London, Paris, Atlanta, and other major domestic and international cities. Through these relationships, Wachtell Lipton was able to bring to bear the best thinking and flexibly address client needs in any market, anywhere. Lipton did not want to supplant the practice of these firms as other New York firms were trying to do, but to work with them in mutually beneficial ways.

The Firm is a meritocracy. Ability is the only requirement for success.

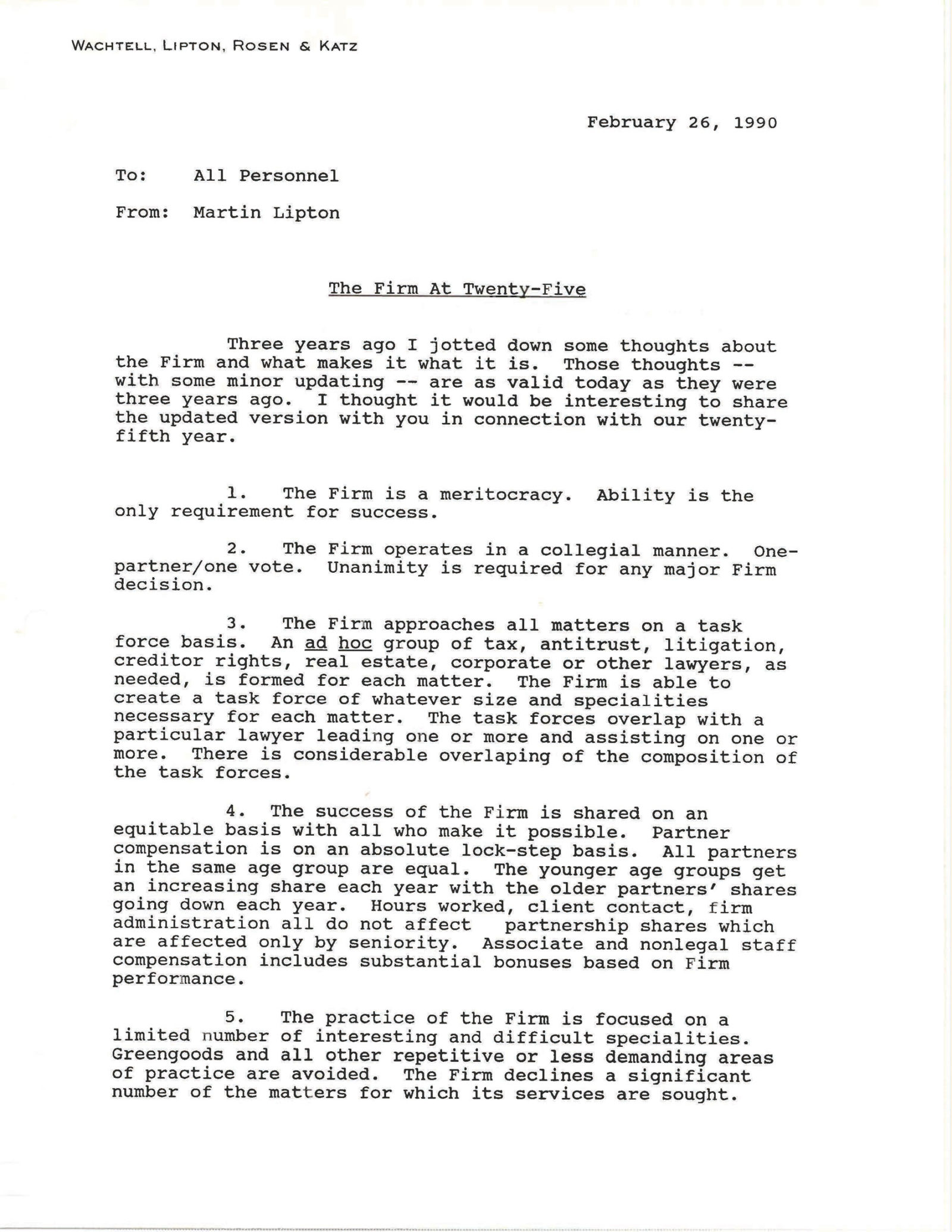

In 1990, Martin Lipton, commemorating the firm’s twenty-fifth year in practice, circulated to all personnel a memo articulating the firm’s cultural and business tenets—“what makes it what it is.”

On the occasion of the firm’s twenty-fifth anniversary, Lipton sent out a memo dated February 26, 1990 to all his partners and the employees of Wachtell Lipton:

Three years ago I jotted down some thoughts about the Firm and what makes it what it is. Those thoughts – with some minor updating — are as valid today as they were three years ago. I thought it would be interesting to share the updated version with you in connection with our twenty-fifth year.

1. The Firm is a meritocracy. Ability is the only requirement for success.

2. The Firm operates in a collegial manner. One partner/one vote. Unanimity is required for any major Firm decision.

3. The Firm approaches all matters on a task force basis. An ad hoc group of tax, antitrust, litigation, creditor rights, real estate, corporate or other lawyers, as needed, is formed for each matter. . . .

4. The success of the Firm is shared on an equitable basis with all who make it possible. Partner compensation is on an absolute lock-step basis. All partners in the same age group are equal. The younger age groups get an increasing share each year with the older partners’ shares going down each year. Hours worked, client contact, firm administration all do not affect partnership shares which are affected only by seniority. Associate and nonlegal staff compensation includes substantial bonuses based on Firm performance.

5. The practice of the Firm is focused on a limited number of interesting and difficult specialities. . . Repetitive or less demanding areas of practice are avoided. The Firm declines a significant number of the matters for which its services are sought.

. . .

7. Lawyers and nonlegal staff share great pride in the quality of the Firm’s work.

. . .

9. The Firm has no branch offices. The Firm has close relations with firms in other cities and prefers to work on that basis. The Firm will not expand by merger.

. . .

11. The Firm encourages its lawyers to teach, lecture, write books and law review articles and participate in bar associations and other professional organizations.

12. The nonlegal staff is highly motivated and a real part of the team.

13. Associates get full responsibility as soon as ready. . . .

. . .

15. Close relationships are maintained with clients who desire such. Personal friendships frequently develop with clients, especially as a result of difficult and hard fought matters. The clients’ interests are paramount in everything the Firm does.

16. The Firm carefully and strictly avoids client and issue conflicts. The Firm does not enter into retainer relationships and maintains complete professional independence.

17. Fees are based on value of services: Firm seeks to limit its availability to those clients who need the services and who understand and accept the Firm’s fees….

. . .

19. Clients are Firm clients not those of individuals.

20. All competitive instincts are turned outward rather than inward; lock-step compensation and one-partner/one-vote democratic governance avoid internal competition.

. . .

23. Firm is not a business; old fashioned professional partnership: no partnership agreement — only a handshake among friends.

24. Firm does not invest with or in clients — only relationships are as lawyers: no partner or associate may serve as a director of a corporation.

25. Firm is a major participant in community philanthropy and maintains two charitable foundations: lawyers active in community. Firm devotes substantial time and funds to pro bono matters.

26. No nepotism.

27. Firm has not deviated from the basic premise on which it was founded twenty-five years ago — if you do a superior job there will be more demand for our services than you can meet.

. . .

29. The Firm is not a full service firm; it often works as co-counsel with other firms and will not continue a client relationship initiated by co-counsel beyond the matter in which it has acted as co-counsel; Firm does not use its takeover practice to expand other relationships; Firm does not have retainer relationships with the retainer fee applicable to any services the client desires.

30. The Firm’s practice is national with most of it corporate and commercial bank clients outside of New York; the Firm has a substantial international practice in its areas of specialization.

31. . . . practice is very high pressured and not suitable for everyone, only those who are prepared to devote their lives to this type of professional practice.

32. Lawyers mostly law review, Phi Beta Kappa, clerkships with outstanding judges, assistant U.S. Attorneys.

33. Firm avoids rigidities of major Wall Street firms, therefore is attractive to the very talented and innovative people who are not happy in an hierarchal structure.

34. Firm’s success in takeover field is not attributable to Wall Street firms not being willing to handle takeovers — those firms were practicing in the takeover area before the Firm — they were not successful and lost the practice because they were not structured to operate on a task force basis and were unwilling to test corporate innovations — like the poison pill — in litigation.

35. Very close personal relationships among the lawyers; close friendships; attitude much like fraternity/sorority; whenever there is a need, there are volunteers to help.248

The 1990s: The Rise of Institutional Investors and Independent Boards

With the Time/Warner decision and the twenty-fifth anniversary of the firm’s founding, the 1990s began auspiciously for Lipton. His views of takeover defense and the decision-making authority of the board were gaining legal and cultural influence, and as the decade unfolded, he became more sanguine about the M&A deals of the era, which tended to be negotiated, strategic mergers.249 Lipton saw these transactions as productive of long-term value and therefore in accord with the national interest.250 Wachtell Lipton represented parties to many of these transactions. During this period, even hostile M&A activity tended to take the form of another industry competitor’s making a non-coercive higher offer for a different strategic transaction.251 And, with the pill validated,252 bidders generally were channeled into the less coercive forum of an election contest, rather than a tender offer, to present their case to the stockholders.

Lipton continued to urge companies to be cognizant of market developments and to stay prepared in order to maintain control over their destinies.253 He pointed out that institutional investors, in their pursuit of short-term value, were eager to see companies do deals and were marshaling their large and growing voting power against poison pills and staggered boards. He advised:

Preparation to deal with mergers and takeovers, either as an acquiror or target continues to be critical. It is only with full understanding of the sometimes rapidly changing dynamics of the merger market that a company can plan to remain independent, be in a position to protect a negotiated merger against an interloper and obtain the highest value for its shareholders.254

On the whole, however, Lipton poured much of his intellectual energy during the 1990s into addressing the mounting pressure for companies to be operated with the goal of maximizing quarterly returns for stockholders. He believed that management for the short term presented a serious threat to economic growth and stability. Lipton’s focus on the board of directors thus broadened from the takeover defense context to corporate governance more generally.

The Quinquennial Election of Directors

Although Lipton was gratified by Delaware’s judicial validation of the rights plan and the deference showed to directors in responding to takeover threats, he was realistic in recognizing that directors were ultimately elected by stockholders, and that stockholders, who were now mostly institutional investors holding other people’s capital, were aggregating voting power into large blocs and using that power to put pressure on boards. The institutional investors wanted to see boards not only being responsive to takeover bids, but also taking corporate actions — such as downsizing, offshoring, leveraging up, and cutting wages — to increase their immediate returns. Lipton viewed this pressure and the concomitant financialization of the economy as increasing the risk of bubbles and subsequent bursts, and he identified a growing urgency for boards to address these risks. Lipton recognized the need, and the benefits, of corporate accountability to investors, but he wanted that accountability to be based on sustainable, long-term productivity, not on quarterly or even yearly returns. In his writings in this era, he advanced ideas to address these issues.

[T]he ultimate goal of corporate governance is the creation of a healthy economy through the development of business operations that operate for the long term and compete successfully in the world economy…. For it is this goal that will ultimately be the most beneficial to the greatest number of corporate constituents, including stockholders, and to our economy and society as a whole.

Lipton’s most ambitious article of the 1990s was designed to reorient the accountability system for corporate boards in a fundamental way that would encourage long-term planning, substantive reporting to investors, and accountability for profitable operations. He conceived a novel framework that gave boards relief from constant pressure campaigns while still subjecting them to robust review, elections, and potential takeover approaches every five years. The article, A New System of Corporate Governance: The Quinquennial Election of Directors, grew out of Lipton’s memoranda and speeches, and it represented an update of his earlier ideas for eliminating takeover defenses in exchange for a more balanced approach to accountability.255 In the article, co-authored with fellow Wachtell Lipton partner Steven Rosenblum, Lipton challenged the view that the primary function of directors was to implement the momentary will of the stockholders. Rather, he posited that the board should focus on sustainable growth, a durable benefit to long-term investors, other corporate stakeholders, and society as a whole. Lipton and Rosenblum observed that the predominant academic view embraced a system of corporate governance that rendered directors and managers powerless in the face of a hostile takeover. These academics presumed “that stockholders, as owners of the corporation, have the intrinsic right to dictate the corporation’s course and receive its profits” and ignored “the quite varied sources and motivations of hostile acquirors” in their embrace of the hostile takeover as “the free-market device to rid corporations of bad managers and give stockholders their entitled profit in the process.”256 Lipton and Rosenblum argued instead that the legal constructs underlying the corporate form required justification “on the basis of economic and social utility, not intrinsic rights” and that the best route to long-term business success was for stockholders, directors, and managers to work cooperatively — particularly in light of “the growing power of institutional stockholders, and their increasing willingness to exercise that power.”257

Lipton and Rosenblum espoused a sweeping view of the role of corporate governance:

[T]he ultimate goal of corporate governance is the creation of a healthy economy through the development of business operations that operate for the long term and compete successfully in the world economy. Corporate governance is a means of ordering the relationship and interests of the corporation’s constituents: stockholders, management, employees, customers, suppliers, other stakeholders and the public. The legal rules that constitute a corporate governance system provide the framework for this ordering. [The] legal rules, the system of corporate governance, should encourage the ordering of these relationships and interests around the long-term operating success of the corporation. For it is this goal that will ultimately be the most beneficial to the greatest number of corporate constituents, including stockholders, and to our economy and society as a whole.258

One of Lipton’s sayings appeared in a page-a-day calendar in November 1988, the year after the movie Wall Street was released.

The policy proposal in Quinquennial was a detailed plan in which every fifth annual stockholder meeting would be “a meaningful referendum on essential questions of corporate strategy and control.”259 The proposal required managers to defend their record and produce detailed, persuasive strategic plans every five years. Between elections, the board would have sole discretion to determine if a bid should be presented to stockholders — i.e., the board could “just say no” in order to pursue its strategic plan unhindered for five years — thereby obviating the need for poison pills and other takeover defenses. The proposal included provisions for proxy access, by which dissatisfied shareholders with significant holdings could contest the quinquennial election, whether to facilitate a hostile takeover or simply to replace underperforming directors. Lipton sought to increase the power of institutional and other investors who were focused on the long term. Lipton believed that when viewed over a more rational time period, the interests of genuine, long-term stockholders and company stakeholders such as workers tended to converge.

Quinquennial thus evidenced Lipton’s growing interest in addressing hostile takeovers through a more effective, comprehensive means than a patchwork of takeover defenses, as well as his fundamental belief that managers and directors should be held accountable to stockholders by serving the interests of long-term investors rather than short-term profit-seekers. Lipton promoted this proposal in speeches and op-eds for several years.260 In the event, Quinquennial was less significant as a proposal for reform than as an articulation of the view that good corporate governance should promote managerial focus on long-term profitability and minimize the threat of activist takeovers in pursuit of short-term gain. The proposal in Quinquennial built upon Lipton’s 1980s takeover defense work and represented another expression of his beliefs that corporations are better understood as republics than direct democracies, and that fiduciaries are bound to exercise their own independent judgment to foster long-term profitability and the best interests of all stakeholders.261

A Modest Proposal

In his second major article of the 1990s, “A Modest Proposal for Improved Corporate Governance,” co-authored with Professor Jay W. Lorsch of Harvard Business School, Lipton built on his prior writings regarding the role of a strong, active board of directors in effective governance.262 The authors argued that corporate governance could be a powerful tool to improve corporate performance, and that the means to implement good governance “should be developed and adopted by corporations on their own initiative and should not be imposed by legislation, regulation, court decisions overruling settled principles of corporate law, or bylaw amendments originated by institutional investors.”263

Outside directors should function as active monitors of corporate management, not just in crisis, but continually.

In Quinquennial, Lipton and Rosenblum had highlighted the rising influence and power of institutional investors. In A Modest Proposal, Lipton and Lorsch addressed the implications of this development. They observed that institutional investors had rapidly increased their equity ownership in the preceding decade to an estimated 50% to 60% of the total value of listed companies. Given that institutional owners were not in a position to “act as owners” or monitors of individual companies — yet would “continue to insist on accountability for poor performance” — the authors concluded that “more effective corporate governance depends vitally on strengthening the role of the board of directors.”264 They cited an important speech given by Delaware’s Chancellor Allen earlier that year for the proposition that the most basic responsibility of directors is “the duty to monitor the performance of senior management in an informed way.”265 Chancellor Allen elaborated, and Lipton and Lorsch quoted:

Outside directors should function as active monitors of corporate management, not just in crisis, but continually; they should have an active role in the formulation of the long-term strategic, financial, and organizational goals of the corporation and should approve plans to achieve those goals; they should as well engage in the periodic review of short and long-term performance according to plan and be prepared to press for correction when in their judgment there is need.266

By every measure, the board of directors is the linchpin of our system of corporate governance, and the foundation for the legitimacy of actions taken by management in the name of the shareholders.

Lipton and Lorsch also quoted remarks by the Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, Richard Breeden, in which he emphasized the central role of the board and the importance of strong oversight in preventing what the authors called “the long-term erosion of corporate performance”:

By every measure, the board of directors is the linchpin of our system of corporate governance, and the foundation for the legitimacy of actions taken by management in the name of the shareholders. The board has the access to information and the power to provide meaningful oversight of management’s performance in running the business, and it needs to use them cooperatively but firmly. This is particularly vital when a company is in a downward spiral, since the cost of waiting for a takeover or bankruptcy to make management changes will be far higher than through board action.267

Lipton and Lorsch averred that the “modesty” of their proposal was to be found in the means of its implementation: “We propose that changes in board practices be implemented by individual boards, with no changes in laws, stock exchange rules, SEC regulations, or new court decisions.”268 The authors identified certain common elements that, in their experience, limited board effectiveness: lack of meeting time, board size, complexity of information provided, lack of group cohesiveness, undue influence of the CEO/chairman, and confusion regarding accountability. Their proposal for improved corporate governance included the following best practices, designed to reduce obstacles to board effectiveness without blurring the distinction between management and oversight:

A. Board Size and Composition:

- The board should be limited to a maximum of 10 directors, with a ratio of two independent directors to every director who has a substantial connection with the company or its CEO.

- Independent directors should be subject to term limits and a mandatory retirement age.

- Every board should have audit, compensation, and nominating committees, each composed entirely of independent directors. Each independent director should serve on at least one of these committees.

- Absent special circumstances, a director should not serve on more than three boards.

- The independent directors should consider meeting separately on a regular basis to avoid any misunderstanding or implication that the independent directors are meeting or conferring because of dissatisfaction with management.

B. Frequency and Duration of Meetings:

- Boards should meet at least bimonthly, with each meeting taking a full day, including committee sessions and other activities. Boards of major corporations may find it useful to meet as often as eight to 12 times per year.

- One meeting per year should be a two- or three-day strategy session.

- Directors should spend the equivalent of a full day preparing for each meeting by reviewing reports and other materials sent to them in advance.

- Director compensation should be raised commensurate with the increased time they are required to spend, which would be more than 100 hours annually for each board, not counting special meetings or travel time.

- Board meeting agendas should allocate the vast majority of the time to activities related to the board’s monitoring role, possibly by creating a board calendar to specify at which meeting the board will carry out various duties and reviews.

C. The Lead Director:

1. Boards without a nonexecutive chairman should appoint a lead director from among the independent directors. The role could be rotated on an annual or biannual basis.

2. The CEO/chairman should consult with the lead director on key matters, and the director should play a leading role in CEO evaluation.

D. Improved Information:

1. Directors should receive a broad array of data, not merely financial reports. The specific data provided depends upon the nature of the business and the adequacy of the company’s information systems.

2. Each board should choose and annually reevaluate the format in which data is organized and presented to ensure maximum utility.

E. Corporate and CEO Performance Evaluation:

1. The board should annually and explicitly conduct a thorough and meaningful assessment of the performance of the company and its leadership.

2. The evaluation should include three aspects:

(a) an assessment of the company’s long-term financial, strategic, and organizational performance in relation to the goals previously established by management and the board;

(b) an annual evaluation of the CEO’s performance by the independent directors; and

(c) a self-assessment of how the board itself is functioning.

F. The Board and Shareholders:

1. The board (including management directors) should meet annually in an informal setting with five to 10 of the significant shareholders in order to promote understanding between the two groups and provide a convenient opportunity for the investors to communicate their concerns.

2. When the company’s performance is not satisfactory, the company should provide investors with more information about the causes of the company’s difficulties, and the actions the board and management are taking to correct the situation, than is normally provided in the “Management’s Discussion and Analysis” section of the company’s periodic reports.

3. If a company has experienced multi-year underperformance, a special section of the annual report should be prepared under the supervision of the independent directors to describe the causes of the problems and the actions the board and management are taking. This special report should be continued annually until the problems have been resolved.

4. When a company’s underperformance triggers this special report, long-term substantial shareholders should be entitled to voice their views through the proxy statement for the annual meeting. The annual meeting should be postponed in order to provide an opportunity for them to do so.269

The key features of Lipton and Lorsch’s recommendations were the proportion of independent directors, the performance reviews for the company and CEO, the annual meeting with significant investors, and the special report to shareholders for troubled companies. These elements laid the groundwork for the board to be, for the first time, a locus of real power separate and apart from management. Others had called for the exercise of director authority to monitor legal compliance, check conflicts of interest, evaluate the performance of top managers, and ensure that succession plans were in place. But Lipton and Lorsch broke ground by coherently outlining a manageable set of proposals that genuinely could empower directors. The authors provided a practical roadmap for boards to be more active and engaged, and to increase accountability at each step of the ladder from managers to directors to investors, without calling for prescriptive mandates or unrealistic reforms. Their recommendations were capable of implementation at the individual board level with the simple adoption of bylaw amendments and procedural changes.

Lipton urged public companies to follow the recommendations of A Modest Proposal. He informed clients when General Motors adopted corporate governance guidelines that “in a number of instances parallel[ed] the recommendations” in A Modest Proposal.270 He again alerted clients when Chief Justice Norman Veasey of the Delaware Supreme Court alluded to the article in a 1994 speech and “gave the impression that the Delaware courts, in reviewing actions by a board of directors of a Delaware corporation, would take into account whether the board had principles like the Modest Proposal and the General Motors Guidelines.”271

Lipton and Lorsch were careful not to overpromise: “We do not argue that good corporate governance produces good corporate performance.”272 Nevertheless, they contended that their proposal, if implemented broadly by the private sector, would be “an effective means for improving corporate governance and thereby improving performance and the competitive position of U.S. companies.”273 In addition, they concluded, widespread adoption of the recommendations at the individual board level would:

reduce the growing tension between activist institutional investors and shareholder advocacy groups and corporations; eliminate much of the proxy resolution activity by institutional investors designed to impose their concepts of governance on companies; arrest the efforts for more federal regulation and legislation; and avoid a judicial shift away from the traditional business-judgment-rule review of board actions.274

Lipton was prescient in his recognition that a company had to be proactive in its approach to investor relations in order to keep control of its own destiny. In one client memo, he put the matter this way:

Institutional shareholder activism is here to stay. It is not going away. Failure to develop good relations with institutional shareholders and refusal to recognize their insistence on being heard when they believe a company is not performing properly will result in confrontations that will not benefit the company or its management. If companies do not develop their own programs, they run the risk of having the institutions’ programs forced on them.275

All of the goals at the heart of A Modest Proposal remained at the forefront of Lipton’s corporate governance agenda throughout the decade. They took on new urgency when corporate crises in the mid- and late-1990s set the stage for regulatory intervention.

The Rise of the Independent Board

After a series of accounting debacles in the 1990s prompted public calls for audit committee reform, Lipton consistently resisted the imposition of a regulatory framework and personal liability on audit committees. He wrote:

The small number of bad financial reporting incidents should not be the impetus for well-meaning but bad law — especially when that law, indeed any law, will not prevent the kind of problem it purports to proscribe. Instead, careful consideration should be made before imposing new duties and potential liabilities on audit committees and directors that may make the cure worse than the ailment. Although the goals of promoting investor confidence and disseminating accurate information are laudable, the costs of imposing rigid rules and new liability exposures on audit committees to achieve this goal overshadows any benefits from the proposed rules.276

Lipton believed that board effectiveness was maximized through flexibility and independence: “Rigid corporate governance rules should generally be avoided. Given the heterogeneity of Corporate America, strict rules limit the ability to tailor guidelines to company-specific needs and may ultimately impede development of unique and improved corporate governance methods.”277 Lipton observed that corporate governance had improved materially over the course of the decade, largely due to the widespread adoption of corporate governance guidelines informed by A Modest Proposal and similar best practice recommendations of the Business Roundtable278 and the ABA Committee on Corporate Laws.279 He identified the root causes of accounting irregularities as the pressure of quarterly earnings announcements and the lack of meaningfully independent auditors.

After representing AT&T in its acquisition of NCR in 1991, WLR&K continued to be involved in many of the company’s merger-and-acquisition deals until 2005, when AT&T was sold to SBC.

Although he did not view board oversight as a silver bullet to stop corporate abuses, Lipton believed that while “there is no compliance program, there is no audit committee that is going to totally prevent fraud or criminal acts by officers of a corporation,” nonetheless, a focus on compliance at the board level “makes an enormous difference.”280 Lipton embraced Chancellor Allen’s iconic 1997 Caremark decision, which was presaged by the Chancellor’s speeches and writings earlier in the decade.281 In Caremark, Chancellor Allen held that boards of directors had an affirmative obligation to ensure that monitoring systems were in place to oversee legal compliance and manage important risks, and that boards were required to act promptly if they learned of circumstances suggesting that, despite the monitoring systems, there existed the potential for legal violations or harms to the company and stakeholders such as communities of operation, consumers, or works.282 At the same time, the Chancellor relied primarily on the force of this normative statement of legal duty to impel director action, and he set the liability bar high, so that directors who made a good faith effort to monitor need not fear liability. The balance struck by Chancellor Allen in Caremark accorded with Lipton’s own sense that judicial admonition and reputational risk are at least as powerful, when it comes to motivating desirable behavior, as the threat of liability.

In a tribute to Chancellor Allen upon his retirement as a jurist, Lipton and his Wachtell Lipton partner Theodore N. Mirvis praised the Chancellor for his “certain grasp of the supremely Delawarean mission of corporate governance.” They wrote:

[O]ne of Chancellor Allen’s enduring legacies will undoubtedly be his reformulation of the proper role and function of the corporate director in a variety of contexts, and the independent director in particular, not only in the celebrated takeover defense case but also in the more significant “everyday” setting in which good corporate governance principles play their most important part.283

In this article and elsewhere, Lipton returned to the key passage in Chancellor Allen’s 1992 speech quoted in Quinquennial, which Lipton described as a “breakthrough” regarding the role of independent directors. Lipton and Mirvis also praised Chancellor Allen for his view of outside directorship “as a private office imbued with a public responsibility.”284 (Some years later, Chancellor Allen would return the compliment, writing with Leo E. Strine, Jr. in 2005: “Nearly as consequential [as the poison pill] was Lipton’s important role in the movement toward increasing the professionalism and power of independent directors.”285) Central to Lipton’s vision of corporate governance was his belief that the active oversight work of independent directors was integral to the prosperity of corporate America.

This vision was to become more relevant than ever to American public policy in the new millennium.

248 Memo: Martin Lipton Memo to All Personnel (Feb. 26, 1990).

249 See, e.g., Memo: The New Merger Wave (July 7, 1997) ; Memo: Mergers — What Next (Dec. 29, 1998).

250 Indeed, at the end of the decade, Lipton defended large strategic mergers as valuable to U.S. competitiveness in a friendly exchange with Ralph Nader. Martin Lipton, Why Big is Good, The Am. Law., June 1998.

251 See, e.g., Memo: Takeovers — An Update (Mar. 14, 1994); Memo: Takeover Response Checklist — Revised (Mar. 18, 1994).

252 The pill not only survived but proliferated in a variety of forms in the 1990s. See, e.g., Memo: The Poison Pill — Current Observations (Mar. 10, 1997).

253 See, e.g., Memo: Am I a Takeover Target? (Aug. 27, 1998).

254 Memo: Merger Activity (Feb. 1, 1997), at 2.

255 Martin Lipton & Steven A. Rosenblum, A New System of Corporate Governance: The Quinquennial Election of Directors, 58 U. Chi. L. Rev. 187 (1991).

256 Lipton & Rosenblum, 58 U. Chi. L. Rev. at 187-88 (citing, inter alia, Frank H. Easterbrook, Daniel R. Fischel, Ronald J. Gilson, and Reinier Kraakman).

257 Lipton & Rosenblum, 58 U. Chi. L. Rev. at 188-89.

258 Lipton & Rosenblum, 58 U. Chi. L. Rev. at 189.

259 Lipton & Rosenblum, 58 U. Chi. L. Rev. at 225.

260 E.g., Martin Lipton, An End to Hostile Takeovers and Short-Termism, Fin. Times, June 27, 1990; Martin Lipton, Address at the Institute of Directors, Institute of Directors: A New System of Corporate Governance: The Quinquennial Election of Directors (Mar. 18, 1991).

261 Over the next two decades, Lipton would find theoretical support in the work of some prominent academics, including Professor Margaret Blair and Professor Lynn Stout, who argued that independent boards were essential players in what the authors called “team production”:

In other words, boards exist not to protect shareholders per se, but to protect the enterprise-specific investments of all the members of the corporate “team,” including shareholders, managers, rank and file employees, and possibly other groups, such as creditors.

Margaret M. Blair & Lynn A. Stout, A Team Production Theory of Corporate Law, 85 Va. L. Rev. 247, 253 (1999), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=425500.

262 Martin Lipton & Jay W. Lorsch, A Modest Proposal for Improved Corporate Governance, 48 Bus. Law. 59 (1992).

263 Lipton & Lorsch, 48 Bus. Law. at. 60.

264 Lipton & Lorsch, 48 Bus. Law. at 60, 61.

265 Lipton & Lorsch, 48 Bus. Law. at 62 (quoting C. William T. Allen, Redefining the Role of Outside Directors In an Age of Global Competition, Address at the Ray Garrett Jr. Corp. & Sec. Law Inst., NW. Univ. (Apr. 30, 1992)).

266 Lipton & Lorsch, 48 Bus. Law. at 62 (quoting Allen, Redefining the Role of Outside Directors In an Age of Global Competition).

267 Lipton & Lorsch, 48 Bus. Law. at 62-63 (quoting Richard C. Breeden, Chairman, S.E.C., Corporate Governance and Compensation, Address at Town Hall of California, L.A., Cal. (June 1992)).

268 Lipton & Lorsch, 48 Bus. Law. at 63.

269 Lipton & Lorsch, 48 Bus. Law. at 67-76.

270 Memo: Corporate Governance (Mar. 24, 1994).

271 Memo: Board of Directors Guidelines on Corporate Governance Issues (June 7, 1994), at 1 (referencing C.J. Norman Veasey, Address at Prentice Hall (June 6, 1994); see also Memo: Corporate Governance (June 20, 1994) (discussing same speech).

272 Lipton & Lorsch, 48 Bus. Law. at 64.

273 Lipton & Lorsch, 48 Bus. Law. at 76.

274 Lipton & Lorsch, 48 Bus. Law. at 76 (emphasis added).

275 Memo: Corporate Governance: Board of Directors Meetings with Institutional Investors (Nov. 30, 1992), at 3.

276 Martin Lipton, Eric Rosenblum, & Janice Liu, A Cautionary Approach to the ‘Report and Recommendations of the Blue Ribbon Committee on Improving the Effectiveness of Corporate Audit Committees,’ 22 Bank & Corp. Gov. L. Rep. 995 (1999).

277 Lipton, Rosenblum, & Liu, 22 Bank & Corp. Gov. L. Rep. at 998.

278 The Business Roundtable, Statement on Corporate Governance, Sept. 1997.

279 American Bar Association on Corporate Laws, Corporate Director’s Guidebook, 2d. Ed. (1994).

280 Martin Lipton, Corporate Governance: Does It Make a Difference?, 2 Fordham Fin. Sec. Tax L. F. 41, 43 (1997).

281 See, e.g., William T. Allen, Our Schizophrenic Conception of the Business Corporation, 14 CARDOZO L. REV. 261 (1992) (based on a lecture given on Apr. 13, 1992 under the auspices of The Heyman Center on Corporate Governance at Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law); William T. Allen, Directors Who Deserve Respect, Directors & Boards (1992), available at https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Directors+who+deserve+respect-a013601069.

282 In re Caremark Int’l Derivative Litig., 698 A.2d 959 (Del. Ch. 1996). For more information about the Caremark case and the remembrances of key participants in the litigation, see the recorded interviews of participants in the case (including Chancellor Allen), and opinions, briefs, and other materials from the case, at Caremark Video, Penn Law, The Delaware Corporation Law Resource Center.

283 Martin Lipton & Theodore N. Mirvis, Chancellor Allen and the Director, 22 Del. J. Corp. L. 927, 928 (1997), https://www.djcl.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/CHANCELLOR-ALLEN-AND-THE-DIRECTOR.pdf.

284 Lipton & Mirvis, 22 Del. J. Corp. L. at 935, 937 (quoting Allen, supra).

285 William T. Allen & Leo E. Strine, When the Existing Economic Order Deserves a Champion: The Enduring Relevance of Martin Lipton’s Vision of the Corporate Law, 60 Bus. Law. 1383, 1391 (2005).