Marty Lipton and the Challenges of a New Century

The Aughts: Defending Board-Centered Governance That Focuses on Sustainable, Responsible Long-term Growth

Addressing the Failures of Oversight at Enron and WorldCom

The high-profile corporate meltdown of Enron in 2001 followed a spate of accounting fraud scandals at the end of the 1990s. The stock market reaction hurt investors, and political pressure grew at the federal level to address a perceived lack of effective controls on excessive risk within American corporations. Lipton understood this as a reasoned reaction, but he hoped to forestall prescriptive federal legislation with what he viewed as more effective and targeted market response. With this in mind, Lipton led the NYSE’s response to the market crisis. Wachtell Lipton worked with the NYSE Legal Advisory Board, of which Lipton was the chair, to develop new corporate governance standards that would improve the ability of public companies to avoid improvident practices, prevent managerial fraud, satisfy regulators, and thereby diminish the risk of market-destabilizing crises and overly intrusive regulation. Under Lipton’s direction, the amendments to the NYSE listing rules focused primarily on director independence rather than specific oversight mandates. As Lipton had signaled in A Modest Proposal, he believed that prescriptive regulation was an undesirable way to achieve reform; his aim, therefore, was to placate the demand for regulatory intervention by codifying certain best practices — many of which had been laid out in A Modest Proposal and were often recommended to clients of the firm — while ensuring that directors retained the latitude and flexibility that he viewed as essential for optimal board performance in a dynamic business environment.

When the WorldCom accounting fraud surfaced in June 2002, the renewed public outcry made federal legislation inevitable, and Lipton and the NYSE turned to the task of trying to make the regulatory interventions as effective as possible. The NYSE’s nimble action to advance listing standards that addressed governance in a comprehensive manner was helpful, as it was a factor in focusing the draft Sarbanes-Oxley legislation more narrowly on particular governance issues relevant to preventing and remedying financial fraud, such as weak internal control practices. When the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) was passed in July 2002 — at which point the NYSE’s proposed listing rules were already in the initial public comment process — its board-level corporate governance requirements addressed only the composition and responsibilities of the audit committee.

The NYSE’s new governance listing standards were approved in final form by the SEC in 2003. The new rules contained detailed requirements for director independence, with heightened independence and financial literacy standards for audit committee members. As Lipton and Lorsch had modestly proposed more than a decade earlier, NYSE-listed companies were now obligated to have fully independent audit, compensation, and nominating/governance committees, board-adopted corporate governance guidelines, and regular meetings of non-management directors, led by an independent “presiding” director.

The societally harmful corporate crises notwithstanding, Lipton remained firmly convinced of the supreme importance of the business judgment rule and that many of the problems that had arisen were because companies were subject to irrational pressures to please short-term-focused investors. He considered broad directorial discretion to be a key driver of American corporate prosperity and positive returns for diversified, long-term investors and that the primary tool for stockholders to hold directors accountable should be their ability to elect a new board. He maintained the importance of protecting the ability of directors to take calculated business risks without incurring personal liability in the event of failure. With the NYSE rule amendments, Lipton sought to preserve this bedrock element of corporate law while improving corporate governance through an integrity-enhancing framework he had long championed.

Implementing Good Governance to Preserve the Business Judgment Rule and Enhance Corporate Integrity

After the adoption of the NYSE corporate governance listing standards and the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, Lipton focused on advising boards on the importance of implementing best practices in governance. With the conviction that widespread adoption and compliance were necessary to prevent further corporate crises and preempt additional regulatory intervention, he wrote prolifically to emphasize the importance of strong boards and promote sound governance. Compared to prior decades, Lipton spent less time negotiating deals and more time advising clients in their efforts to effectuate good governance and defend against shareholder activism. His advisory, strategy, and policy efforts — to shape the intellectual debate as well as provide guidance to market participants and regulators — were amplified by his public communications.286

[P]ost-Enron regulations will be effective only if accompanied by fundamental changes in corporate culture.

In 2002-2003, Lipton formulated his thoughts in a speech and paper titled, “The Millennium Bubble and Its Aftermath: Reforming Corporate America and Getting Back to Business”:

The burst of the “Millennium Bubble” of the late 1990s and early 2000s and the ensuing collapse of corporate giants such as Enron have, as in past collapses, resulted in a crisis in investor confidence and an economic downturn of such magnitude as to threaten deflation. The response has been congressional hearings, investigations, prosecutions and sweeping new regulation — to express our condemnation of the conduct that created the crisis, to punish corporate wrongdoers and to impose structural, procedural and behavioral requirements to reduce the likelihood of the crisis’s recurrence.

… First, post-Enron regulations will be effective only if accompanied by fundamental changes in corporate culture. To bring about true reform, those who are regulated must share the goals embodied in the rules that they are obligated to follow. Second, in our efforts to restore confidence in our markets, we must guard against overregulation and overzealous prosecutions, as these may stifle the recovery of our economy.287

Lipton identified several Wall Street causes of the millennium bubble crisis, including the pressure of quarterly earnings reports, the credulity or complicity of research analysts, “excessively deferential boards and short-sighted compensation structures for senior management.”288 He believed that the reforms that had been adopted, if genuinely embraced by Wall Street, would suffice to revive the economy and restore investor confidence. To that end, he made great efforts to advise clients to “share the goals embodied in the rules that they are obligated to follow.”289

In 2002, Lipton wrote client memos specifically encouraging directors to:

- formalize the role of the lead director, in order to strengthen the hand of independent directors and to blunt calls for separation of the roles of CEO and chairman of the board;290

- schedule longer board meetings and an annual two- to three-day board retreat with senior executives to undertake a full review of the company’s financial statements and disclosure policies, strategy and long-range plans, and current developments in corporate governance;291

- annually review the competence of the key partners and managers of the accounting firm who were responsible for the audit as well as a formal policy of not hiring from the accounting firm any partner or manager who worked on the corporation’s account during the past three years;292 and

- recognize that a “tectonic shift” in corporate power from management to the board and shareholders requires adherence by all participants in corporate America to the new SOX and NYSE corporate governance rules and, moreover, to “the highest ethical standards,” for the good of the national economy.293

Lipton also advocated for greater oversight of accounting firms. Writing with Professor Jay Lorsch of the Harvard Business School, he proposed the legislative creation of an independent, self-regulatory organization to oversee accounting firms. This solution, they wrote, “would leave accounting in the private sector with self-regulation, not government regulation, but would provide the government involvement that has now become critical to restore confidence.”294 Their recommendation, published in February 2002, was essentially fulfilled through the creation of the Public Company Accounting and Oversight Board by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act later that year. On the company side, Lipton advised boards of directors “to review the practices and procedures of audit committees to improve their effectiveness and help restore investor confidence.”295

The business judgment rule is alive and well.

Beyond the objective of improving corporate performance, Lipton had two further aims in advocating for widespread adoption of good governance practices. The first was to head off calls for further government regulation. In the wake of WorldCom’s bankruptcy, Lipton was fighting a strong current. Former SEC Chairman Richard Breeden, the court-appointed “Corporate Monitor” for the bankrupt WorldCom/MCI, generated a report containing seventy-eight corporate governance recommendations, prompting Lipton to make a strong case against imposing particularized oversight obligations on boards. He called Breeden’s report “a case-specific set of recommendations seeking to right the wrongs committed by a most extreme example of corporate wrongdoing.”296 Lipton wrote:

Taken as a whole, Breeden’s recommendations would strait-jacket and enfeeble boards of directors and undermine their ability to effectively guide their corporations — the exact opposite of what Breeden says he intends, and the exact opposite of what is needed in the current environment. . . . Wanton piling-on of further new rules and restrictions will be counterproductive. . . . There is no formula for the perfect board.297

Second, Lipton advocated that the widespread adoption of corporate governance standards would help to preserve the liability protections of the business judgment rule. Although he perceived jurisprudential erosion of the business judgment rule to be a less likely risk than increased regulation, he nonetheless reminded clients at every opportunity that good governance protected directors.298 In a memo to clients regarding audit committee procedures, Lipton observed that directors could safely rely on external advisors so long as they had no reason to doubt the experts’ competence or loyalty.299 His recommended additional procedures for audit committees were intended — in addition to improving the quality of audit committee oversight — to ensure that the directors did not forfeit the protections of the business judgment rule by failing to do their diligence regarding the external auditors. He also emphasized that the same principles applied beyond the context of the audit committee. In a 2002 article in M&A Lawyer, Lipton and his colleague Laura A. McIntosh advised, with a note of warning:

While there is no change in the fundamental legal principles applicable to the duties and responsibilities of boards of directors, there is a clear change in attitude by investors and the public at large that could manifest itself in adverse judicial decisions and further legislation.300

Lipton worried that greater exposure to liability, in addition to burdensome responsibilities, would reduce the quality of directors willing to sit on public company boards. At the end of 2002, he wondered aloud in a client memo: “Now the issue is whether the new corporate governance requirements go too far and will result in discouraging competent people from serving as directors and deter management from taking appropriate entrepreneurial risks.”301 Regarding two high-profile 2003 cases — Disney and Abbott Laboratories — in which directors were at risk of personal liability for failure of oversight, he wrote:

[T]here is no doubt that the courts are applying a high level of scrutiny to allegations of board misconduct, including failure to exercise oversight where there was clear indication of need for it. But the courts also continue to recognize that, if large public companies are to attract experienced persons who will not be petrified into excessive risk-aversion by the possibility of personal liability, independent directors must be given adequate judicial protection for their decisions where the record shows that they took the time to deliberate and to exercise oversight.302

After the 2005 WorldCom settlement, in which the WorldCom directors were subject to $18 million in personal, out-of-pocket settlement payments, Lipton again assured directors that the protections of the business judgment rule remained robust, though he acknowledged that there was reason for concern:

In the current environment, there is a huge and growing demand on the part of regulators, enforcement agencies and the public for “personal accountability” on the part of all corporate actors. . . . Thus, there remains a serious risk that the strong foundations of the business judgment rule and the traditional deference shown to corporate managers and outside directors are being slowly eroded. Some of the post-Enron, post-Sarbanes-Oxley expectations being placed on senior managers and outside directors, are both unrealistic and unfair.303

The final 2005 Disney decision in the Delaware Chancery Court provided a welcome affirmation that, in Lipton’s oft-repeated phrase, “the business judgment rule is alive and well”:

The decision in the Disney case alleviates the concern raised by the Enron and WorldCom settlements that the post-Enron accounting and corporate governance reforms would diminish the business judgment rule and create new bases for director liability. Despite the ruling in the Disney case, however, boards should not lose sight of the fact that the post-Enron reforms have imposed new responsibilities on directors.304

As it became clear that public company directors had entered a new era of significantly increased burdens and potentially greater exposure, Lipton developed two quasi-annual client memos specifically for directors. The first was a bullet-point, one-page format called “Key Issues for Directors,” the first of which was distributed in December 2003. The second was a longer, advisory piece titled “Some Thoughts for Directors,” the first of which was sent to clients in January 2004.305

M&A in the 2000s

Meanwhile, at the turn of the millennium, merger and acquisition activity was high.306 Lipton recommended that clients stay prepared for all aspects of merger activity and ensure alignment between the board and management as to the company’s fundamental strategy. He also advised that companies stay attuned to their major investors:

[T]here should be full appreciation of what the major shareholders expect and the likely reaction by them and the analysts to any merger action. Without the confidence of the shareholders and the analysts, major mergers run the risk of failure and successful rejection of takeover proposals is almost impossible.307

Lipton began to take a broad view of merger activity in his writings, particularly with regard to its role in corporate governance and the overall health of the economy. He offered his perspective on the historical context of M&A in an extensive 2001 client memo titled, “Mergers: Past, Present, and Future,” which provided an overview of U.S. merger activity from the 1890s to 2001.308 He also continued to update clients on current developments in dealmaking.309 And, as he had in the past, Lipton followed global developments in M&A and kept his clients up to date. In January 2002, he called attention to a proposed European Union Takeover Directive, which Lipton viewed as “effectively hanging a ‘For Sale’ sign on all EU companies” by prohibiting the poison pill, allowing squeeze-outs at 90%, and mandating break-through of shark repellants at 75% ownership.310 Against Lipton’s better judgment, the EU Takeover Directive was adopted in 2004 and continues to govern some nations in the European Union.311

On the practice front, Lipton and Wachtell Lipton remained actively engaged in M&A transactions. Lipton felt that the strategic mergers that were prevalent in the 1990s were more likely to be based on sound business principles than the leverage-up mergers and unsolicited takeover bids of the 1980s. As private equity matured and leading private equity firms emerged with a record of successfully running companies, Wachtell Lipton also become more involved in representing sellers to private equity as well as private equity buyers.

At the same time, Lipton continued to assert that boards of directors should have the power to determine the future of their companies, and should not be pressured into M&A transactions motivated by short-term interests. He would soon confront the new challenges presented by activist hedge funds whose approaches were intended to force companies involuntarily into sale mode or to take other short-termist actions, at the same time that institutional investors were successfully pressuring companies to dismantle their takeover defenses in the name of shareholder rights.

The Twentieth Anniversary of the Poison Pill: University of Chicago Symposium

Though the poison pill was, by 2002, a firmly established feature of corporate law and governance, Lipton continued to defend it against academic attacks. In advance of a University of Chicago Law School symposium on the pill’s twentieth anniversary that year, Lipton summarized his adversaries’ positions:

Today there are three schools of pill traducers, each led by a prominent law school professor, and each advancing a different means and rationale for doing away with the pill. One school endorses a shareholder initiated amendment to the bylaws to require redemption of the pill and to prohibit reissuance. Another, recognizing the likelihood that the bylaw invalidating the pill will be held illegal, at least in Delaware, advances bylaw amendments that do not directly attack the pill, but have the effect of undermining a board’s ability to use it. The third would amend state corporation laws to provide that a raider could made a takeover bid and force a shareholder referendum, which if supported by a majority of the outstanding shares would override the pill and all other structural defenses to the bid.312

The well-settled legality of the pill was the unspoken assumption behind this generation of arguments, which were far removed from the existential challenges to the pill that were brought in the 1980s. In his contribution to the symposium, Lipton summarized twenty years of argumentation, legislation, and litigation regarding the poison pill: “[Over two decades] I have sought to preserve the ability of the board of directors of a target of a hostile takeover bid to control the target’s destiny and, on a properly informed basis, to conclude that the corporation remain independent.”313 He observed that much of the academic criticism in the symposium centered around the theoretical ability of a board to resist a takeover indefinitely, when in reality dissatisfied shareholders had always had — and indeed, in some cases, had successfully wielded — the power to replace all or part of an unyielding board:

As the creator and principal proponent of the pill, I think it fair to say that the pill was neither designed nor intended to be an absolute bar. It was always contemplated that the possibility of a proxy fight to replace the board would result in the board’s taking shareholder desires into account, but that the delay and uncertainty as to the outcome of a proxy fight would give the board the negotiating position it needed to achieve the best possible deal for all the shareholders, which in appropriate cases could be the target’s continuing as an independent company. The pill and the proxy contest have proved to yield the perfect balance, both hoped for and intended, between an acquiror and a target. A board cannot say “never,” but it can say “no” in order to obtain the best deal for its shareholders.314

Leading academics and jurists contributed pieces to the symposium, including:

Bebchuk. Professor Lucian Bebchuk argued that boards should not have the ability to block hostile takeover offers, assuming that mechanisms are in place to ensure shareholders’ undistorted choice.315 After reviewing theoretical and empirical arguments in favor of board veto and concluding that they were insufficient to warrant such authority, he posited that boards should be able to delay an acquisition only for the period needed for the board to prepare alternatives for shareholders’ consideration and that incumbent directors should not be allowed to continue to block a takeover offer after losing one contested election.

Kahan and Rock. Professors Marcel Kahan and David B. Rock contended that Delaware’s judicial sanctioning of the poison pill and the “just say no” defense turned out to be far less consequential than it seemed at the time. They cited increased board independence and incentive compensation as two legal developments that transformed the poison pill into a device that was, if anything, beneficial to shareholders. They observed:

None of the parade of horribles predicted by partisans came to pass. Though takeover tactics have changed somewhat, the takeover game has continued along, its pace determined more by macroeconomic factors than by the details of legal doctrine, with new modes of gaining control developing as older methods have become more difficult. Most strikingly, despite judicial and legislative rejection of the academics’ preference for relatively unrestricted hostile takeovers, and despite the granting of great discretion to managers to reject acquisition proposals that their shareholders might want to accept, merger and acquisition activity reached record levels during the 1990s.316

Arlen. In her contribution, Professor Jennifer Arlen responded to Professors Kahan and Rock, arguing that, notwithstanding private adaptive devices such as board independence and option-based pay for top managers that create incentives for them to be receptive to takeover bids, the legal regime governing takeovers remained potentially determinative of shareholder choices in many takeover situations. Therefore, she argued, when the existing legal regime is not optimal, it can distort the results of private contracting, particularly where contingencies unforeseen by the shareholders (such as the board’s use of the poison pill and other possible defensive measures) exist and influence shareholder preferences.317

Allen, Jacobs, and Strine. In their symposium paper, three Delaware jurists — retired Chancellor William T. Allen, Vice Chancellor Leo E. Strine, Jr. (later Chancellor, and then Chief Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court), and Vice Chancellor Jack B. Jacobs (later a Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court) — offered a meditation on Delaware jurisprudence. They reflected that Delaware law occupies a middle ground between the “property model,” in which the purpose of the corporation is to maximize the wealth of stockholders, and the “entity model,” in which, by giving directors latitude to use the poison pill and block takeover offers, Delaware law affords directors room to consider the interests of stakeholders.318

Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom” Twenty-Five Years Later: Leading Thinkers Reflect on Lipton’s Seminal Work

Three years after the Chicago symposium, The Business Lawyer published a series of articles celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of Lipton’s Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom. The contributions were not just reflections on the article itself, but on Lipton’s larger view about the proper role of corporations in society and the way that corporation law should facilitate that role. The symposium included pieces by many leading corporate law scholars and practitioners, as described below.

Lipton. Lipton’s own assessment was that the “first battle” had been won:

At its core, Takeover Bids argued that a corporation’s board of directors should be permitted, and indeed has a duty, to manage actively the business of the company, and that its discretion in doing so should not depend on the nature of the particular issue that is being decided (so long as the board satisfies its fiduciary duties). Those theories — a rejection of board passivity, an endorsement of the board as gatekeeper and an active role by the board in the context of hostile takeover bids — became part of the public discourse after the publication of Takeover Bids and were ultimately affirmed, either tacitly or explicitly, by both common law and legislative guidance. In short, that battle was won.319

Lipton reviewed the Delaware Supreme Court’s Unocal decision, with its proportionality test for director-enacted takeover defenses and the mandate that directors focus on the impact of the bid on non-shareholder constituencies, which cited to a Lipton article based on Takeover Bids. Lipton noted the Court’s rejection of the notion of the board as a “passive instrumentality”; the acceptance of the shareholder rights plan or “poison pill,” which he characterized as having “naturally followed” from Delaware’s acceptance of the board’s “threshold role” in takeovers; and the widespread adoption by state legislatures of “constituency” statutes allowing directors to consider non-stockholder factors such as the interests of employees, customers, suppliers and local communities as well as the long-term interest of the company.320 At the same time, Lipton predicted “new, and perhaps more dangerous, battles” arising from the burst of the “Millennium Bubble” of the late 1990s and early 2000s and the regulatory responses to the collapse of great companies such as Enron and WorldCom.321 In that regard, Lipton characterized the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and related rulemaking as “regulatory zeal and ‘activism’ gone awry,” fostering an “over-engineering of board structure” and increased shareholder “empowerment” (citing, in particular, to the SEC’s 2003 proposal to grant stockholders the right to use the company’s proxy statement for director nominations and increased pressure from shareholder groups to influence day-to-day management) as “quite dangerous” and “ridiculous,” singling out the argument of Professor Lucian Bebchuk of the Harvard Law School as “the equivalent of governance by [shareholder] referendum.”322

Allen and Strine. The contribution by former Chancellor William T. Allen and then-Vice Chancellor Leo E. Strine, Jr. cited Lipton as having “almost certainly … been more influential in the development of American corporate law and governance practices than any other private lawyer.” Allen and Strine characterized Lipton’s view as “the Institutionalist View” which “sees business corporations as social institutions authorized by law in order to facilitate improvements in public welfare,” and they noted Lipton’s success over “the Finance View” which “sees the current value of the firm’s equity securities. . . . as the best way to measure the productivity of the corporation.”323 They wrote:

On that front of the economic policy battlefield that involves the contest over the appropriate takeover policy of substantive corporate law, Lipton can take pride in the extent to which his arguments in Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom have been adopted. Even more dramatically, his audacious originality produced the innovation of the poison pill and its intellectual defense. However one feels about the social utility of the device, almost certainly the pill represents the most important private law innovation in the field of corporate law of the last fifty years. Nearly as consequential was Lipton’s important role in the movement toward increasing the professionalism and power of independent directors. Lipton seized upon the emergence of independent board majorities as additional intellectual ballast for his argument that boards should be trusted to decide whether and to what buyer corporations should be sold or merged.324 To his continuing delight, many scholars holding the Finance View bemoan the rejection of their perspective by Delaware and other states and find themselves constantly reworking their policy proposals in order to come upon one that can shake the grip of the director-centered approach to takeovers that is at the heart of Lipton’s Institutionalist View.325

Gilson and Kraakman. Professors Ronald J. Gilson and Reinier Kraakman, in their contribution, asserted that Lipton’s Takeover Bids was a deeply conservative “Burkean take on a messy Schumpeterian world” that had since moved from the nemesis of the “two-tier, front-end-loaded, boot-strap, bust-up, junk-bond hostile tender offers” to a “new market for corporate control” dominated by strategic bidders who (it was argued) no longer posed the threats of the corporate control markets of the 1980s.326 In their view, Takeover Bids was “a call to arms in the defense of an economic order built on the honor, perspicuity, and civility of the officers and directors of America’s corporations” — and thus Burkean in the sense of “an impassioned defense of an ancien regime authored by a powerful mind.”327 The professors rehearsed the academic opposition to Lipton’s position (principally, the anti-defense writings of Professors Easterbrook, Fischel, Bebchuk and themselves). And they purported to identify a schism between Delaware’s Supreme Court and its Court of Chancery — wherein Chancery had attempted to follow a “pragmatic” fact-driven assessment of defensive tactics post-Unocal, whilst in the Supreme Court (it was asserted), “Lipton’s conservative ideology ultimately prevailed” with that court’s having bought Lipton’s platform “hook, line and sinker.”328

Stout. Professor Lynn A. Stout offered a different academic perspective, positing that Lipton’s core claim — that directors should be granted authority to decide if the company should be sold — was proving correct both as a positive statement of the law and, more importantly, as a normative matter of sound policy.329 Professor Stout surveyed recent literature on the efficient market theory and principal-agent theory, and suggested there had been “a sea change in academic thinking.”330 That development, it was argued, had led many scholars to agree with (or at least consider anew) the claims in Takeover Bids that stock market prices often fail to reflect a company’s true value and that hostile takeovers threaten the interests of important corporate non-shareholder constituencies such as managers, employers, creditors, customers, and communities.

Balotti, Varallo, and Czeschin. Delaware attorneys R. Franklin Balotti, Gregory V. Varallo, and Brock E. Czeschin (all three of the Richards Layton firm) traced the “explicit[] and implicit[]” reliance by the Delaware Supreme Court on Takeover Bids and Lipton’s other writings in its fashioning of the Unocal standard of review for defensive conduct. They concluded that Lipton’s writings “have had a marked — even profound — influence on the development of Delaware takeover jurisprudence.”331

Shareholder Activism and the Role of Institutional Investors

The two symposia reflected the significance of Lipton’s work over the prior decades. It became clear, however, as the Aughts progressed, that larger market developments — in particular, the rapidly growing voting power of institutional investors and the impact of shareholder activism — were overtaking the importance of takeover defenses per se. Institutional investors were using their influence to pressure boards to drop defenses such as pills and classified boards, at the same time that shareholder activism was increasing in intensity and ambition. In Lipton’s 2002-2003 Millennium Bubble article, he had predicted the growth in shareholder activism that would occur during the first decade of the 2000s:

The burst of the bubble, the public outcry against corporate abuses and the resulting plethora of enacted or proposed rules and recommendations have increased the potential oversight role of the shareholder. We should expect shareholders to be (or attempt to be) more actively involved in matters that were heretofore reserved for the board and management. . . . And they have begun to fight for access to their companies’ proxy statement for board nominations. . . . We should expect this issue to yield extensive debate in the near future.

These initiatives, coupled with the momentum and general sentiment that shareholders were wronged by those within the company whom they trusted, have created a much more activist shareholder. We should expect more proxy fights for full control of corporations, exertion of shareholder influence through withhold-the-vote campaigns and greater use of proxy resolutions to bring matters to a shareholder vote at annual meetings.

While some proxy solicitations by shareholders and some shareholder initiatives may lead to improved company performance, it is of critical importance that irresponsible and narrowly self-seeking shareholders and shareholder advisory organizations not be allowed to take advantage of reaction to the scandals to impose new requirements on corporations and their directors and officers that decrease rather than increase their effectiveness.332

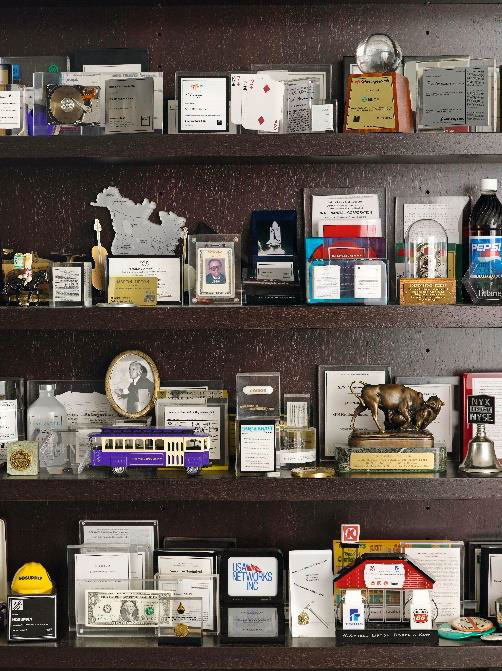

Although Lipton did not agree with Chancellor Allen’s Interco decision, the two had great respect and affection for each other. Here, they discuss Interco and Time-Warner at Penn in a session moderated by then Vice Chancellor, and long-time Penn faculty member, Leo Strine, Jr.

Lipton’s predictions regarding the direction of shareholder activism proved largely correct. Shareholder activists pushed hard for proxy access in the early part of the 2000s. In 2003, the SEC issued proposed amendments to the proxy rules that would permit shareholders to nominate director candidates in the company proxy statement.333 And along with proxy access, activists sought so-called majority voting — a term for turning a decision not to grant a proxy into a “no vote” by requiring that a director receive a majority, not a plurality, of votes, even if unopposed, in order for the director to remain in office. Led by public and union pension funds and supported by mainstream mutual funds, activists proposed precatory proxy resolutions providing for majority vote requirements. The SEC did not permit companies to exclude these precatory proposals, and Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) expressed support for them. The American Bar Association announced consideration of an amendment to the Model Business Corporation Act to require a majority, rather than a plurality, vote for directors. Lipton made his views clear in a 2005 client memo:

Requiring a majority vote would give activists huge leverage by allowing them to threaten to withhold enough votes to defeat a nominee even though the withheld votes are substantially less than a majority of the outstanding shares. This shift in leverage to special interest activists would also be a further deterrent to competent people accepting nominations as directors.

While there is surface appeal to a majority vote requirement, it thus has the potential to cause serious disruption of the existing system.334

More generally, Lipton was concerned to see that takeover defenses were being taken down in a large swath of the market in response to activist pressure, and he felt that the increase in activist hedge fund attacks had become a serious enough threat to the ability of corporations to concentrate on responsible, long-term growth to warrant serious preparation on the part of public companies. In 2006, Lipton released a formal “Hedge Fund Attack Response Checklist,” much like the takeover defense checklists he had pioneered in the 1980s:335 “The current high level of hedge fund activism warrants the same kind of preparation as for a hostile takeover bid. In fact, some of the attacks are designed to facilitate a takeover or to force a sale of the target. Careful planning and a proactive approach are critical.”336

During the 2006 proxy season, Lipton took aim at the positions espoused by Professor Bebchuk as epitomizing a misguided view of shareholder empowerment:

As noted in the Wall Street Journal last week, Prof. Lucian Bebchuk of the Harvard Law School has personally submitted proposals for binding bylaw amendments to at least 10 major American corporations, turning these very real companies — with combined annual revenues in excess of $450 billion and employing more than 850,000 individuals — into his private “case studies.”

. . .

[T]hese skillfully-worded proposals … increase shareholder power while reducing or neutralizing the role of the board of directors in safeguarding the interests of the corporation. More importantly, they form part of a larger but misguided campaign on the part of certain academics and special-interest activist shareholders to impose upon the corporate landscape a shareholder-centric governance model that is at odds with the fundamental construct of our corporate law and that runs contrary to some of the best current thinking — among both academics and practitioners — about corporate governance and long-term corporate performance.

. . .

Referenda votes by diverse bodies of shareholders with conflicting objectives cannot begin to substitute for the situation-specific business judgment of a skilled and experienced board. In short, these are serious matters, and turning these companies into the experimental play-things of a handful of special-interest activists and academics with an ideology to advance (or publicize) is not in the national interest.337

Bebchuk’s proposals included a mandatory amendment providing that the adoption of a poison pill would require a unanimous board vote and that any pill adopted could have a term of only one year. Lipton criticized Bebchuk’s proposal on the grounds that it would substitute the judgment of a single director for the judgment of the full board, and that it would destroy the staggered board by empowering a single director, elected the first year in a contested election, to veto any attempted renewal of the poison pill.338

The key issue for American business is whether the institution of the corporate board of directors can cope with shareholder activism and survive as the governing organ of the public corporation.

In addition to engaging with Bebchuk and other academics as to theories of governance and impractical proposals for reform, Lipton’s primary focus became addressing the influence and behavior of shareholder activists such as ISS, the Council of Institutional Investors (CII), public pension funds, union pension funds, and activist hedge funds. Activist favored-positions on corporate governance that put companies under immediate market pressures were quickly becoming mainstream; in 2006, both the Model Business Corporation Act and the Delaware General Corporation Law were amended to facilitate majority voting. In 2007, Lipton wrote

The key issue for American business is whether the institution of the corporate board of directors can cope with shareholder activism and survive as the governing organ of the public corporation. Will a forced migration from director-centric governance to shareholder-centric governance overwhelm American corporations?

The fundamental questions are: (1) whether we will be able to attract qualified and dedicated people to serve as directors and (2) whether directors and the companies they serve will become so risk-averse that they lose the entrepreneurial spirit that has made American business great.339

Lipton feared that corporate governance measures that increased the prevalence of independent directors more beholden to institutional investors — which was originally intended to empower independent boards to improve the performance of troubled companies and to act as a bulwark against conflict of interests and possible overreaching, a la Enron, in the pursuit of pleasing the market — was being co-opted by influential interest groups more interested in short-term profit and their own accumulation of power than in sustainable growth for long-term investors, the consideration of the welfare of stakeholders, and the prosperity of the American economy. He brought to clients’ attention a 2007 study by three leading academics indicating that the corporate governance indices touted by shareholder activists bore no relation to corporate performance. The authors’ conclusion was one that Lipton had long championed:

[C]orporate governance is an area where a regulatory regime of ample flexible variation across firms that eschews governance mandates is particularly desirable, because there is considerable variation in the relation between the indices and measures of corporate performance.340

There is no justification for revolutionizing corporate law and corporate practices so that shareholders replace directors as the fundamental arbiters of corporate policy.

The following year, Lipton alerted clients to another research study, the first to evaluate commercial governance ratings such as the Corporate Governance Quotient (CGQ) rating that had become an influential product of ISS (which for a brief time was renamed RiskMetrics). The authors found that CGQ “exhibits virtually no predictive validity” with respect to either positive future firm performance or avoidance of undesirable outcomes such as accounting restatements or shareholder litigation. Lipton summarized the findings thus:

The Stanford study confirms that one-size-fits-all governance ratings are of little predictive value and do not deserve the talismanic power they have assumed in today’s overheated corporate governance environment. Companies and boards of directors should embrace governance structures and programs that are appropriate to their specific circumstances, taking into account generally accepted “best practices” as appropriate, but not go out of their way to raise their company’s governance “scores” for their own sake. Shareholders should be skeptical of entrepreneurial self-styled authorities who peddle their creations as new standards that will increase the value of a company’s stock.341

Although Lipton long had encouraged companies to maintain open lines of communication with their largest shareholders,342 he viewed with apprehension the creeping trend toward governance by constant referenda. In 2007 he released a brief client memo bemoaning the announcement by Pfizer that its board of directors would invite its largest institutional shareholders to a meeting to give the shareholders the opportunity to comment on Pfizer’s governance, including executive compensation. Lipton saw this as “another example of corporate governance run amuck.”343 He elaborated:

Since 2002 there has been a steady escalation of demands by corporate governance activists to increase shareholder power over the business decisions of boards of directors. With academic support from Prof. Lucian Bebchuk of the Harvard Law School, activists are seeking to impose prospective and retrospective referenda on basic decisions by boards of directors.

There is no justification for revolutionizing corporate law and corporate practices so that shareholders replace directors as the fundamental arbiters of corporate policy. Basic corporate law . . . is the only proven vehicle for organizing and deploying capital on the large and dynamic scale of the modern United States economy. It should not be overturned by desperate attempts to appease deconstructionist activists.344

As shareholder activism became entwined with a push for direct democracy and ballot access, Lipton presciently warned:

The fundamental governance issue confronting corporations in 2007 will be the extent to which shareholders should have the ability to intervene in board actions and influence business decisions that have traditionally been within the purview of the board of directors. This will manifest itself in: (a) debates on executive compensation and the ability to recruit and retain world-class executives, (b) proposals for annual shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation, (c) majority voting proposals and withhold-the-vote campaigns, (d) continuing efforts by activists to achieve proxy access for shareholder-nominees for election as directors, (e) continuing attacks on takeover protections, (f) efforts to mandate shareholder referenda on material decisions, (g) challenges in recruitment and retention of qualified and skilled directors, (h) requests by institutional shareholders for direct communications with directors and (i) demands by activist shareholders for short-term stock performance rather than long-term value creation.345

Lipton warned that frequent shareholder intrusions into corporate governance — rather than having shareholders express their views primarily through the election process, in which an alternative slate of directors was properly presented for consideration — effectively could displace the board of directors as the governing organ of the public corporation and “overwhelm American business corporations.”346

Lipton also identified an extensive series of problems, the combined effect of which, in his view, threatened American entrepreneurship and productivity:

- Pressure on boards from activist investors to manage for short-term share price performance rather than long-term value creation.

- Potential for embarrassment of directors from corporate scandals in which they had no active participation.

- The shift in the board’s role from guiding strategy and advising management to ensuring compliance and performing due diligence.

- The corrosive impact on collegiality from the balkanization of the board into powerful committees of independent directors and from the overuse of executive sessions.

- The pressure to shift control of the company from the board to shareholders.

- The executive compensation dilemma [which involved tying top management pay to total stock return to encourage them to manage to the stock market, and increasingly severing their pay from any reasoned relationship to the pay of the rest of the workforce].

- The demand by public pension funds for direct meetings with independent directors.

- The publication of corporate governance ratings and report cards intended to embarrass directors.

- The continuing narrowing of the definition of director independence.

- The constant cycle of new corporate governance proposals.

- The constantly increasing time demands of board service that restrict the ability of active senior business people to serve on boards.

- The unpleasantness of filling out extensive questionnaires to enable appropriate disclosures and qualification determinations.

- The demeaning effect of the parade of lawyers, accountants, consultants and auditors through board and committee meetings.

- The growth of shareholder litigation against directors as a big business and a type of extortion.

- Policies of politically motivated institutional shareholders to refuse to settle lawsuits against directors unless they contribute to the settlement from their personal funds.

- The proliferation of special investigation committees of independent directors, with their own independent counsel, to look into compliance and disclosure issues.347

His concerns grew more acute after the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008.348 He observed that decoupling of voting power and economic ownership was becoming more common, fueling activists’ ability to exert pressure and giving hedge funds control over more votes than their true ownership warranted.349

In 2009, in an op-ed collaboration with Jay Lorsch and Theodore Mirvis, Lipton took to the pages of the Wall Street Journal to oppose Senator Charles Schumer’s proposed legislation, the Shareholder Bill of Rights Act of 2009. Although the stated goal of the bill was “to prioritize the long-term health of firms and their shareholders,” Lipton argued that its provisions would have the opposite effect: “Excessive stockholder power is precisely what caused the short-term fixation that led to the current financial crisis.”350 Lipton warned that in the longer term, shareholders were not the only ones to pay the price of short-termism; as the financial crisis showed, employees, communities, suppliers, creditors, and other stakeholders were hard hit by corporate collapse. Lipton wrote of these constituencies: “They have a legitimate stake in this debate.”351

During the Aughts, Lipton repeatedly emphasized the consequentiality of the debate over corporate governance control. Of board-centric governance, he wrote:

I believe it is the only way to assure that public corporations will be able to compete with the state corporatism that is transforming the economies of China, Russia and other rapidly industrializing countries, cope with the demands for short-term (and short-sighted) stock gains by activist hedge funds and make the long-term investments in the future of their businesses that are essential for future prosperity of our nation.352

Lipton believed corporations to be not predominately as vehicles for short-term stockholder profit but as engines of sustainable, economic growth with a moral duty to society and an essential role in national prosperity and power. The stakes, therefore, could not be higher, and Lipton understood the need to address the reality of unprecedented institutional investor power. Many of the institutions thrived primarily because they held the capital of American working-class investors, whose interests required sustainable, socially responsible corporate governance. Lipton therefore began to consider ways to align the behavior of institutional investors with the needs of their true stakeholders, including American workers. His insights led him to develop a New Paradigm for corporate governance, which was to be fully articulated in the coming years.

The 2010s: The New Paradigm and the Resurgence of Stakeholder Governance

Activist Threats and Corporate Governance in Crisis

As the 2010s began, Lipton continued to focus on the fundamental debate between board- and shareholder-centric governance. Lipton had a weather eye on an emerging force in corporate governance — activist hedge funds — that put pressure on companies to change their business strategies in fundamental ways, either by selling the company or increasing its payouts to stockholders. The term “hedge funds” was something of a misnomer, because unlike hedge funds that helped investors and companies temper risk by “hedging” financial downsides such as expected energy costs, these activist funds took advantage of the latitude in the SEC’s Section 13(d) reporting rules to acquire substantial, but not controlling, stakes in public companies before making public disclosure, and then engaging in a pressure campaign against the company. These activists had a symbiotic relationship with certain other institutional investors, including public pension funds and mutual funds, which had continued to push companies to abandon defenses like classified boards, turn withhold votes into tools to unseat directors, and use annual say-on-pay votes not to address the substance of pay plans, but as a pressure tactic if a company had a poor year. These changes in governance to move toward direct plebiscites facilitated the efforts of activists who could exert pressure on boards to either comply with their demands or risk ouster. Activist maneuverings also received a boost from proxy advisors, who applied a lower standard to proxy contests seeking to seat only a minority of the board, thereby giving activists the ability to argue that the board should be spiced up with new flavors of the activists’ choosing. With the ability to get the support of proxy advisors, and the tools to take advantage of periodic downturns to present stockholders with a vote on their proposals, activists began to exert a large influence on corporate policies. As Lipton wrote in 2014:

The power of the activist hedge funds is enhanced by their frequent success in proxy contests when companies resist the short-term actions the hedge fund is advocating. These proxy contest successes, in turn, are enabled by the outsized power of proxy advisory firms and governance reforms that weaken the ability of corporate boards to resist short-term pressures. The proxy advisory firms are essentially unregulated and demonstrate a general bias in favor of activist shareholders. They also tend to take a one-size-fits-all approach to policy and voting recommendations without regard for or consideration of a company’s unique circumstances. This approach includes across-the-board “withhold votes” from directors if the directors fail to implement any shareholder proposal receiving a majority vote, even if directors believe that the proposal would be inconsistent with their fiduciary duties and the best interests of the company and its shareholders. Further complicating the situation is the fact that an increasing number of institutional investors now invest money with the activist hedge funds or have portfolio managers whose own compensation is based on short-term metrics, and increasingly align themselves with the proposals advanced by hedge fund activists. In this environment, companies can face significant difficulty in effectively managing for the long-term, considering the interests of employees and other constituencies, and recruiting top director and executive talent.353

Lipton viewed most of the gains from activism as ephemeral, with upward ticks in short-term stock price — because a company was sold or increased its buyback programs — disadvantaging long-term investors and stakeholders The increased stock price did not reflect a fundamental improvement in company performance, but was instead the result of a financial gimmick in which value was shifted from the long-term to the short-term, from stakeholders like real investors, workers, and creditors to profiteers and activists. Of equal concern to Lipton was the widespread check-the-box approach to corporate governance and the constant threat of disruption to board authority created by calls for shareholder referenda on particular issues.

Roughly a decade after Lipton led the drafting of the NYSE’s corporate governance rules — a decade in which he had worked to promote the widespread adoption and substantive implementation of good governance354 — he had come to believe that governance initiatives had gone astray:

Having served as a member of the NYSE committee that created the NYSE’s post-Enron corporate governance rules, I have watched with dismay as those rules have been misunderstood, misapplied and polluted by one-size-fits-all “best practices” invented by proxy advisory services and other governance activists.355

Lipton was disappointed to see that certain of the NYSE’s recommendations had produced unintended negative effects on board functioning. He was critical of proxy advisory firms for overburdening directors with process-oriented responsibilities and, as a general matter, “exalt[ing] the board’s monitoring functions over its equally important strategic advisory functions.”356 Wachtell Lipton submitted a comment letter to the SEC in 2010 describing the “outsized influence” and “pervasive, inherent structural conflict[s]” of proxy advisory firms and calling for regulation to increase the accountability of these firms to issuers and investors.357

Shareholder activism reached new heights in the 2010s, and Lipton resisted activist efforts to undermine the ability of boards to chart a sound, long-term direction. For that reason, he continued to oppose further attempts by activists and other institutional investors to push managing-to-the-market policies and to make it easier for short-term investors to influence company strategy. He opposed the idea of subsidizing activists’ proxy fights by allowing them to use the company’s proxy to seek votes, a development that came to be known as “proxy access.” The road to proxy access had been paved by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010, which reaffirmed the authority of the SEC to issue a proxy access rule. The SEC did approve a proposed proxy access rule in August of 2010, prompting Lipton to describe the policy as “[o]ne of the most sweeping new reforms on the horizon.”358 Ever pragmatic, he predicted that, even if the SEC’s proposed proxy access rules were defeated in a legal challenge, “it is likely that activists will pursue shareholder proposals and bylaw amendments to impose proxy access on a company-by-company basis.”359 Activists had indeed used the latter approach to eliminate classified boards and implement majority voting at U.S. public companies, particularly those in the S&P 500. The SEC’s proposed rule was struck down by the D.C. Circuit and vacated before it became effective, but, as Lipton had foreseen, a number of public companies did adopt and implement forms of proxy access on their own initiative.

Lipton also sought to strengthen the 13(d) reporting regime to address the exploitation of regulatory reporting gaps by activist investors. Wachtell Lipton had initially circulated a proposal for modernizing the reporting system in 2008, highlighting investors’ use of swaps and other equity derivatives “to exert influence over corporate decisionmaking with little or no apparent duty to disclose the existence or nature of these positions or their plans.”360 The firm followed up by filing a formal rulemaking petition with the SEC in 2011 citing “the urgent need to amend the existing reporting framework to keep pace with market realities and abuses, in particular by closing the Schedule 13D ten-day window between crossing the 5% disclosure threshold and the initial filing deadline, and adopting a broadened definition of ‘beneficial ownership’ to fully encompass alternative ownership mechanisms.”361

Airgas and Its Aftermath: The Poison Pill Lives in Law, But Declines in Relevance

In 2011, with predatory activism on the rise, the Delaware courts first directly faced the question whether a board of directors could stand behind a poison pill and “Just Say No” in the wake of the 1990 Time/Warner decision of the Delaware Supreme Court, which had strong dictum to that effect (including a non-too-subtle disavowal of Interco) but did not involve a pill. In the intervening period, most hostile takeover disputes had been resolved in a less stark way than a ruling in court, either through a proxy contest leading to some resolution or the emergence of a higher bid from a different party. In Airgas,362 the pill issue was unavoidably presented. Airgas, the target of an all-cash/all-shares bid, had both a staggered board and a poison pill, an indisputably independent board, a charismatic founder and CEO who held ten percent of the shares, and a management team that enjoyed strong support from most analysts and that had just put in place a long-term plan that promised significant growth based on a major investment in SAP. Airgas was a mid-cap firm started some twenty years before, with a market capitalization of under $5 billion. Fittingly, Airgas was represented by Wachtell Lipton.

Air Products’ attempted hostile takeover of Airgas raised governance issues amounting to a reexamination of the poison pill’s validity. The final opinion from the Delaware Chancery Court supported the board’s right to prioritize its vision of the company’s long-term value over the immediate all-cash offer that shareholders, in theory, might have preferred. Result: the poison pill’s efficacy—allowing a target board to “just say no”—was proven.

The hostile bid came from Air Products, a primary competitor of Airgas. Air Products’ initial public bid was announced on February 4, 2010, at $60/share. After Airgas’s board rejected that bid, Air Products raised its bid three times while mounting a proxy contest at Airgas’s 2010 annual meeting (to be held in September 2010) to seat three new independent directors. Air Products also proposed a bylaw that would have required Airgas to hold its next “annual” meeting in January 2011, four months later.

The three Air Products nominees won election, and the stockholders also approved the “annual” meeting bylaw. Airgas challenged the bylaw as inconsistent with Delaware’s classified board statute (DGCL § 141(d)). The Court of Chancery upheld the bylaw, but the Supreme Court held it invalid, and required that annual meetings must be spread “approximately” one year apart.363

The poison pill lives.

When the three Air Products nominees joined the Airgas board, they hired their own legal advisors, and, at their request, a new financial advisor was engaged to take a fresh look at the valuation issues. The Air Products nominees ultimately joined the other directors in rejecting Air Products’ newly increased “best and final” bid of $70/share, even as the board stated its willingness to negotiate with Air Products for a sale of the company were it to raise its bid to $78/share. That set the stage for a second trial on Air Products’ request that the Court of Chancery order Airgas’s board to pull the pill. (A previous trial had been held on Air Products’ pull-the-pill request as to its then-$65.50/share offer, but no decision was rendered while the parties litigated the validity of Air Products’ proposed bylaw to require a second “annual” meeting in January 2011, which could have given Air Products’ nominees two-thirds of the Airgas board in relatively short order.)

The Airgas board’s position was stark. It did not contend that there was a need for additional time for stockholders to be informed. It did not claim a need to search for alternative bids or implement new business strategies. It did not assert that it had any confidential information that indicated any hidden value. It did not doubt the ability of Air Products to consummate its offer. It did not argue that independence was better for the employees or any other non-stockholder constituency. Chancellor William B. Chandler III opened his post-trial opinion by framing the issue presented, and his conclusion, as follows:

This case poses the following fundamental question: Can a board of directors, acting in good faith and with a reasonable factual basis for its decision, when faced with a structurally non-coercive, all-cash, fully financed tender offer directed to the stockholders of the corporation, keep a poison pill in place so as to prevent the stockholders from making their own decision about whether they want to tender their shares — even after the incumbent board has lost one election contest, a full year has gone by since the offer was first made public, and the stockholders are fully informed as to the target board’s views on the inadequacy of the offer? . . .

In essence, this case brings to the fore one of the most basic questions animating all of corporate law, which relates to the allocation of power between directors and stockholders. That is, “when, if ever, will a board’s duty to ‘the corporation and its shareholders’ require [the board] to abandon concerns for ‘long term’ values (and other constituencies) and enter a current share value maximizing mode?” More to the point, in the context of a hostile tender offer, who gets to decide when and if the corporation is for sale?364

. . . For the reasons much more fully described in the remainder of this Opinion, I conclude that, as Delaware law currently stands, the answer must be that the power to defeat an inadequate hostile tender offer ultimately lies with the board of directors. As such, I find that the Airgas board has met its burden under Unocal to articulate a legally cognizable threat (the allegedly inadequate price of Air Products’ offer, coupled with the fact that a majority of Airgas’s stockholders would likely tender into that inadequate offer) and has taken defensive measures that fall within a range of reasonable responses proportionate to that threat.365

In the course of his opinion, Chancellor Chandler repeatedly noted that he felt “constrained”366 and “bound”367 by the Delaware Supreme Court precedents in Time/Warner and other cases, while expressly his “personal” view that the Airgas pill had exhausted its purpose. The Chancellor expressed considerable admiration for Chancellor Allen’s analysis in Interco some thirteen years before, but held that Time/Warner and other precedents permitted the Airgas board to block the Air Products bid if it had a reasonable belief that the offer was too low and there was a real risk that the stockholders (in the event, arbitrageurs) would tender regardless of their views as to the inadequacy of the price offered).

In a crucial footnote, Chancellor Chandler said this about where Delaware law was in reality about a board’s ability to use a pill and how it should be summarized:

Our law would be more credible if the Supreme Court acknowledged that its later rulings have modified Moran and have allowed a board acting in good faith (and with a reasonable basis for believing that a tender offer is inadequate) to remit the bidder to the election process as its only recourse. The tender offer is in fact precluded and the only bypass of the pill is electing a new board. If that is the law, it would be best to be honest and abandon the pretense that preclusive action is per se unreasonable.368

Not surprisingly, Lipton’s scholarship and advocacy, and the contrary views it elicited from the academics, were featured in Chancellor Chandler’s opinion. The Chancellor indeed placed the issue he was obliged to decide squarely within the Lipton-academy debate:

Marty Lipton himself has written that “the pill was neither designed nor intended to be an absolute bar. It was always contemplated that the possibility of a proxy fight to replace the board would result in the board’s taking shareholder desires into account, but that the delay and uncertainty as to the outcome of a proxy fight would give the board the negotiating position it needed to achieve the best possible deal for all the shareholders, which in appropriate cases could be the target’s continuing as an independent company. . . . A board cannot say ‘never,’ but it can say ‘no’ in order to obtain the best deal for its shareholders.” Martin Lipton, Pills, Polls, and Professors Redux, 69 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1037, 1054 (2002) (citing Marcel Kahan & Edward B. Rock, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Pill: Adaptive Responses to Takeover Law, 69 U. Chi. L. Rev. 871, 910 (2002) (“[T]he ultimate effect of the pill is akin to ‘just say wait.’”)). As it turns out, for companies with a “pill plus staggered board” combination, it might actually be that a target board can “just say wait . . . a very long time,” because the Delaware Supreme Court has held that having to wait two years is not preclusive.369

. . .

The merits of poison pills, the application of the standards of review that should apply to their adoption and continued maintenance, the limitations (if any) that should be imposed on their use, and the “anti-takeover effect” of the combination of classified boards plus poison pills have all been exhaustively written about in legal academia. Two of the largest contributors to the literature are Lucian Bebchuk (who famously takes the “shareholder choice” position that pills should be limited and that classified boards reduce firm value) on one side of the ring, and Marty Lipton (the founder of the poison pill, who continues to zealously defend its use) on the other.

The contours of the debate have morphed slightly over the years, but the fundamental questions have remained. Can a board “just say no”? If so, when? How should the enhanced judicial standard of review be applied? What are the pill’s limits? And the ultimate question: Can a board “just say never”? In a 2002 article entitled Pills, Polls, and Professors Redux, Lipton wrote the following:

As the pill approaches its twentieth birthday, it is under attack from [various] groups of professors, each advocating a different form of shareholder poll, but each intended to eviscerate the protections afforded by the pill. . . . Upon reflection, I think it fair to conclude that the [] schools of academic opponents of the pill are not really opposed to the idea that the staggered board of the target of a hostile takeover bid may use the pill to “just say no.” Rather, their fundamental disagreement is with the theoretical possibility that the pill may enable a staggered board to “just say never.” However, as . . . almost every [situation] in which a takeover bid was combined with a proxy fight show, the incidence of a target’s actually saying “never” is so rare as not to be a real-world problem. While [the various] professors’ attempts to undermine the protections of the pill is argued with force and considerable logic, none of their arguments comes close to overcoming the cardinal rule of public policy — particularly applicable to corporate law and corporate finance — “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”370

Well, in this case, the Airgas board has continued to say “no” even after one proxy fight. So what Lipton has called the “largely theoretical possibility of continued resistance after loss of a proxy fight” is now a real-world situation.371

Interestingly, in his closing argument, Air Products’ counsel pressed the accurate (but anachronistic) point that Lipton’s original writings on the pill, such as his 1979 Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom, had not claimed a right for a board to block a tender offer based solely on price. Counsel argued that “Marty Lipton himself has argued that takeovers of the type here are not abusive and the decisions about whether to accept them should be decisions of the stockholders.”372 Counsel played a video clip to the Court in which Lipton, being interviewed about his invention of the pill, described the early 1980s as a period characterized by ten-day tender offers that generated huge pressure on shareholders and management to respond, which led to his probing to find something that would be useful — not in preventing hostile takeovers — but giving the board of directors of the target company an opportunity to level the playing field and have time to make a rational business judgment decision as to how to deal with a takeover.373 Counsel further sought to rely on Lipton for Air Products’ position by pointing to Lipton’s early writings that focused on the financing and timing abuses in tender offers of that period, and later writings in which Lipton had proposed that pills and other structural devices should be eliminated if timing and other tender offer abuses were eliminated by requiring all offers to be fully financed and open for 120 calendar days, and only shareholders who held shares for 60 days prior to the tender offer were allowed to vote.374 As to Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom, counsel’s argument, somewhat quixotically given the Supreme Court’s strong dictum in Time/Warner, was that Lipton’s central argument — that the board of directors should be permitted to exercise its business judgment to determine what offers are and are not in the corporation’s best interests — had been rejected by the Delaware courts, and that the pill’s legitimate purpose was limited to dealing with the pressures of coercive two-tier tender offers made on very short time frames.375

Air Products abandoned its bid within hours of losing in the Court of Chancery — precluding, as in Interco, the Delaware Supreme Court from itself addressing the issue.

Lipton and his colleagues applauded Chancellor Chandler’s opinion in a client memo issued the next day, entitled “Delaware Court Reaffirms the Poison Pill and Directors’ Powers to Block Inadequate Offers.” The memo’s conclusion: “The poison pill lives.”376 Lipton wrote:

Almost thirty years ago, our Firm announced there was a way — the poison pill — to level the playing field between corporate raiders and a board of directors acting to protect the interests of the corporation and its shareholders. Despite great skepticism about the pill in the legal and banking communities, the Delaware Supreme Court in 1985 agreed with us and affirmed that directors, in the exercise of their business judgment, could properly use the pill to protect the corporation from hostile takeover bids.

Since then, many have continued to criticize the pill, and hostile bidders and plaintiffs’ lawyers have continued to litigate to constrain its use. Yesterday, in a historic decision, the Delaware Court of Chancery rejected the broadest challenge to the pill in decades. . . . The decision reaffirms the vitality of the pill. It upholds the primacy of the board of directors in matters of corporate control under bedrock Delaware law. It reinforces that a steadfast board, confident in management’s long-term business plan, can block opportunistic bids. We represented the target, Airgas, and its board of directors.

The conduct of the Airgas board, the Chancellor concluded, “serves as a quintessential example” of these fundamental principles: if directors act “in good faith and in accordance with their fiduciary duties,” the Delaware courts will continue to respect a board’s “reasonably exercised managerial discretion.” Directors may act to protect the corporation, and all of its shareholders, against the threat of inadequate tender offers. And they may act to protect against the special danger that arises when raiders induce large purchases of shares by arbitrageurs who are focused on a short-term trading profit, and are uninterested in building long-term shareholder value. The Chancellor could not have been clearer that “the power to defeat an inadequate hostile tender offer ultimately lies with the board of directors.” And it is up to directors, not raiders or short-term speculators, to decide whether a company should be sold: “a board cannot be forced into Revlon mode any time a hostile bidder makes a tender offer that is at a premium to market value.” The Chancellor concluded: “in order to have any effectiveness, pills do not — and cannot — have a set expiration date.” The poison pill lives.377

Lipton’s memo, while justifiably triumphant in part, reflected the potentially narrow scope of the Airgas ruling. What Lipton called “the special danger” of large purchases by arbitrageurs, focused on trading profits and not long-term value, indeed appears to have been a key, if not decisive, factor in the Airgas ruling. The opinion carefully noted the unusual circumstance that, as both sides agreed, nearly a majority of the Airgas shares were held by arbitrageurs and those who bought below $70/share would tender “regardless of the potential long-term value”; it described the “articulated risk” that “arbitrageurs with no long-term horizon in Airgas will tender, whether or not they believe [with] the board that $70 clearly undervalues Airgas.”378 As the Chancellor noted: “In this scenario, therefore, even the analysis urged by [Professors] Gilson and Kraakman would seem to support the board’s use of the pill.”379

Airgas was also unusual in that its management proved its case in the real world. When the Air Products $70 “best and final” bid was withdrawn, Airgas’s stock price soared in the market. The stock price exceeded $70/share consistently within weeks, and exceeded $80/share within months. Ultimately, Airgas was sold in September 2016 to Air Liquide, for $143/share — double the “best and final” Air Products bid.

Airgas’s pill ruling led, perhaps ironically, to the near demise of the staggered board and also to a sharp decline in poison pills themselves. Buoyed by institutional investors’ willingness to use their power to vote for precatory resolutions to get rid of staggered boards, the “Harvard Law School Shareholder Rights Project” led a campaign to propose such resolutions across Corporate America. The push was led by Professor Lucian Bebchuk at the Harvard Law School, who had long argued that the combination of the pill and a classified board was unfairly preclusive of stockholders’ right to accept attractive bids — a proposition Lipton continued to controvert. In 2010, 146 of the S&P 500 had staggered boards. By 2012, only 89 did. By 2020, the number had dropped to 55.380 Lipton decried the Harvard Law School Shareholder Rights Project. In a March 21, 2012 client memo entitled “Harvard’s Shareholder Rights Project is Wrong,” Lipton wrote:

The Harvard Law School Shareholders Rights Project (SRP) recently issued joint press releases with five institutional investors, principally state and municipal pension funds, trumpeting SRP’s representation of and advice to these investors during the 2012 proxy season in submitting proposals to more than 80 S&P 500 companies with staggered boards, urging that their boards be declassified. The SRP’s “News Alert” issued concurrently reported that 42 of the companies targeted had agreed to include management proposals in their proxy statements to declassify their boards — which reportedly represented one-third of all S&P 500 companies with staggered boards. The SRP statement “commended” those companies for what it called “their responsiveness to shareholder concerns.”

This is wrong. According to the Harvard Law School online catalog, the SRP is “a newly established clinical program” that “will provide students with the opportunity to obtain hands-on experience with shareholder rights work by assisting public pension funds in improving governance arrangements at publicly traded firms.” Students receive law school credits for involvement in the SRP. The SRP’s instructors are two members of the Law School faculty, one of whom (Professor Lucian Bebchuk) has been outspoken in pressing one point of view in the larger corporate governance debate. The SRP’s “Template Board Declassification Proposal” cites two of Professor Bebchuk’s writings, among others, in making the claim that staggered boards “could be associated with lower firm valuation and/or worse corporate decision-making.”