Martin Lipton’s Formative Years As A Lawyer And The Early Years Of Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz

The Formative Years

Martin Lipton was born on June 22, 1931 in Jersey City, New Jersey, where he grew up. His mother, Fannie, concentrated on raising Marty and the home front, and his father, Samuel Lipton, was the manager of a lingerie manufacturing plant owned by his brother.

Lipton was a good student and hoped to study the humanities in college.1 But, his father encouraged him instead to study business. To that end, Lipton attended and graduated from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania in 1952. After graduation, Lipton’s father hoped he would go to work for an investment bank, but Lipton did not find that pathway — which was very different in the 1950s than today — of interest. As he put it, “You didn’t just walk into an investment bank and say, ‘I want to be an associate,’ as you do now.’… There weren’t these great jobs for aspiring bankers. All you could get was being a registered rep or salesman of one kind or another. I thought what I’d really like to be is a lawyer.”2 Intrigued by the law, Lipton put in a late application to the then emerging School of Law at New York University, in part because its recent Dean had been Arthur T. Vanderbilt, who had become the Chief Justice of Lipton’s home state, New Jersey.3

I thought what I’d really like to be is a lawyer.

When Lipton entered NYU in autumn 1952, the law school building had been named Vanderbilt Hall after the former Dean. Lipton loved the study of law and excelled at NYU, being selected as editor-in-chief of the Law Review, and earning a coveted Root-Tilden Scholarship, which had been designed as part of the plans of Vanderbilt and his successor, Dean Russell Niles, to attract outstanding students from all around the United States to NYU Law School. After being selected for Law Review, Lipton met his future partners Herbert Wachtell, Leonard Rosen, and George Katz, who were law review editors in the year ahead of him.4 In fact, as Lipton recalled it, “My friendship with Herb got off to a rocky start when he took the first note I wrote for the Law Review and completely rewrote it on his typewriter amidst a constant stream of criticism. Fortunately, I survived the experience — as did our nascent friendship, which is still going strong after six decades.”5

Herbert Wachtell ‘54

Martin Lipton ‘55

Leonard Rosen ‘54

George Katz ‘54

Because of Lipton’s academic success, Dean Niles encouraged Lipton to consider a teaching career focusing on corporate law, a subject in which he had developed a particular interest. Niles wanted to groom Lipton to join the NYU faculty, and arranged a post-graduate fellowship for Lipton to study under the legendary Professor Adolf Berle at Columbia Law School. Berle was the author of the iconic 1932 book, The Modern Corporation and Private Property, and numerous other important publications on the role of corporations in society, and one of the “Brain Trusters” who helped President Roosevelt develop and implement the New Deal. During the period he studied with Berle, Berle encouraged Lipton to write his thesis on the growing power of institutional investors, a subject generations ahead of most scholars’ times and a topic that was to become central to Lipton’s later career and thinking. But, Dean Niles had also encouraged Lipton to round out his preparation for a career in academia with a few years of practical experience.

Adolf Berle (1895 – 1971) gives a speech at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City, circa 1950

Lipton served for two years as Judge Edward Weinfeld’s clerk before joining the Seligson, Morris & Neuburger firm, where his law school friends Len Rosen and George Katz already had jobs.

Thus, another prominent Columbia Law Professor, Herbert Wechsler, helped Lipton secure a clerkship in 1956-57 with Judge Edward Weinfeld of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Near the end of Lipton’s clerkship, Dean Niles recommended that he spend a couple of years at a law firm specializing in corporate law, the field that most interested Lipton, so that he could round out his experience before a career in teaching.

Lipton then joined the small but distinguished business law firm of Seligson, Morris & Neuberger, where he had worked as a summer intern before his Columbia Fellowship. The senior partner of the firm, Charles Seligson, taught at NYU and Lipton had been a student in Seligson’s bankruptcy course. The Seligson firm specialized in corporate law and creditors’ rights, and represented such major companies as Schenley Industries, Metromedia, and Pepsi-Cola, and worked with Lehman Brothers for clients that were involved in proxy fights, corporate control, and securities law matters. By dint of his work on securities law matters and his relationship with Dean Niles, Lipton was asked to step in and teach securities law at NYU on short notice after the death of a faculty member.

Lipton with early client J. P. Burroughs Company, a Michigan sand, gravel and farm machinery company.

Lipton found that he enjoyed being able to practice law and teach law, and decided to eschew a full-time career in academia to become a partner at the Seligson firm, while continuing to teach at NYU. In 1962, Lipton became a partner in the firm, along with his law school friend, Leonard Rosen, who he had helped get a job with the firm. In 1964, Rosen and Lipton asked another NYU law friend, George Katz, to leave his firm and join them at the Seligson firm as a partner. During his time at the Seligson firm, J. Lincoln “Pud” Morris took a special interest in Lipton, and Lipton worked closely with Morris on complex corporate and securities matters. As part of the mentoring process, Morris taught Lipton how to interact with chief executives and investment bankers, introduced him to the charms and business utility of being a regular with a good table at “21,” encouraged him to dress the part, and gave Lipton an education in the social graces important to being not just an effective business lawyer, but a public citizen. Morris’s commitment to professional excellence, careful preparation, and adherence to high standards of ethics was also something he helped deepen in Lipton himself.6

Basically, the firm was a group of friends joining together and we did not view it as a business. We shook hands, said that we would practice law together, and agreed to be equal partners. Our basic understanding was simply that we would work hard, do a great job, and clients would seek us out.

When the Seligson firm dissolved in December of 1964, Lipton, Rosen, and Katz decided to form their own law firm. They had remained friends with their law school confrere, Herb Wachtell, and had regularly referred litigation matters to him. Lipton, Rosen, and Katz decided to invite Wachtell and his partner, Jerome Kern, another NYU grad, to join their new firm. Thus, in 1965, Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen, Katz & Kern was formed. As Lipton described it, “The firm started as four friends. This wasn’t a business proposition. As younger people came into the firm, they became our friends. We had a dozen people and we were all friends. We had two dozen people and we were all friends. And so on. . . . We decided to moderate the growth and keep it small. I guess we also just didn’t want to have a situation where people thought they were working for us rather than that they were part of a family.”7 Or as he put it another time, “Basically, the firm was a group of friends joining together and we did not view it as a business. We shook hands, said that we would practice law together, and agreed to be equal partners. Our basic understanding was simply that we would work hard, do a great job, and clients would seek us out. To this day, that principle guides the firm [we created] and the firm [still] does not have a written partnership agreement.”8

Although Lipton was the primary mover in creating the firm, he and his friend Herb Wachtell divided the senior partner spoils, with Wachtell being first in the firm’s name, and Lipton being first named partner on the letterhead. But, as Wachtell happily admits, “His name is second. . . It’s always been a team effort, but we all know that Marty has always been first among equals.”9

Lipton grew the firm based on his values — a firm that was based on mutual trust, a commitment to professional excellence, and thought leadership. Building on their NYU affiliations, the firm recruited other talented NYU graduates and faculty, and it encouraged its lawyers to engage in law school teaching and publishing. The firm specialized in corporate, securities, creditors, and tax law. During the 1960s, Lipton himself specialized in M&A transactions and public offerings for smaller companies, and on defending clients in SEC enforcement proceedings.10 He and the firm got their first taste of real public attention near the end of the ‘60s, when Lipton led the successful defense of Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers, a major mid-western distributor of Pepsi against hostile takeover bids, and facilitated its later $100 million friendly merger — a big number in that period — with Illinois Central Industries.11 The firm’s involvement in M&A resulted in a change in its name, when Lipton’s partner, friend and founding partner, Jerome Kern, left to become an investment banker, and leaving the firm’s name as Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, or “Wachtell Lipton.”12

America Goes To The Moon, and Lipton Invents the “Marty Memo”

Around the end of the 1960’s, Lipton hit on what was then a novel way of communicating his thoughts that became a hit with clients, other lawyers, influential corporate advisors like investment banks, and eventually policy leaders, a way integral and important to his practice and thought leadership over the rest of his career.

During that period, developments at the Securities Exchange Commission, and in securities law in general, were at the forefront for lawyers working internally at large, public companies. Lipton got positive feedback when he sent out short, to-the-point, memos — which he aimed to be no more than one page if possible — that put new developments in relevant terms that general counsel, top corporate officers, and corporate advisors could grasp and put into practice. Not only that, Lipton’s memos, as will be seen, had a “voice” and a point of view, unlike the lengthier, “on the one hand, on the other” approach, that often characterized legal discourse of that time.

Over the years, the “Marty memo” and firm writings drawing on its template became the major way that Wachtell Lipton communicated with clients and found new clients, as over time, more and more company counsel, CEOs, investment bankers, and even other law firms, asked to be on the distribution list to hear the thoughts of Lipton and his partners. The memos kept readers abreast of key developments in securities and corporate law, and over time, increasingly contained Lipton’s views on the best corporate practices for addressing important issues. For a more complete overview, see the introduction to the collection of Lipton’s articles and memos at the archive section on this site.

M&A During the “Me” Decade: Real World Experiences With Hostile Takeovers Shape Lipton’s View of the Proper Role of Corporations in Society

Lipton’s increasing prominence as a result of the Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers matter and his growing voice, through his memos, lectures, and leadership in making M&A and securities law a major focus of important conferences of lawyers and scholars, led to Wachtell Lipton gaining a larger share of the expanding M&A field.

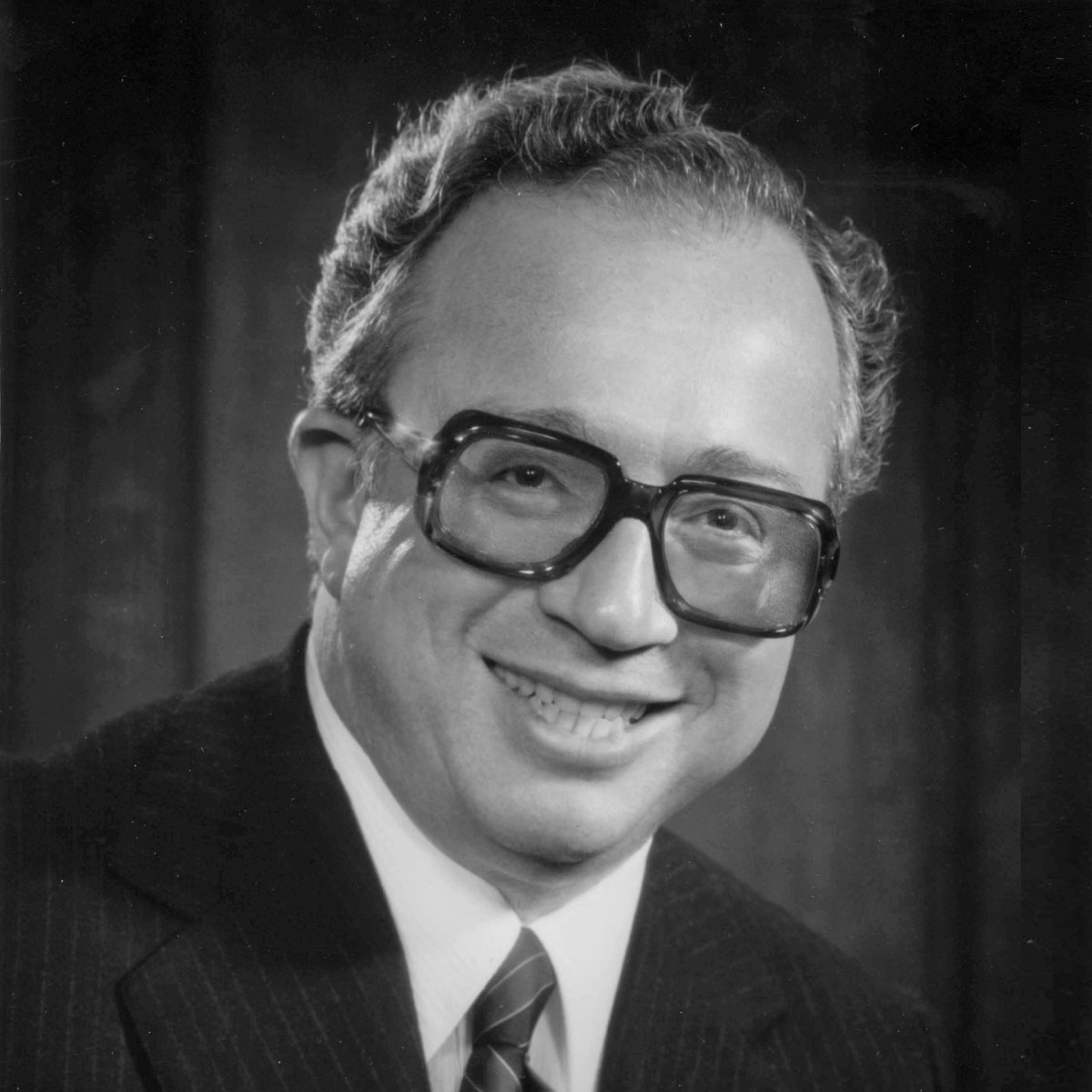

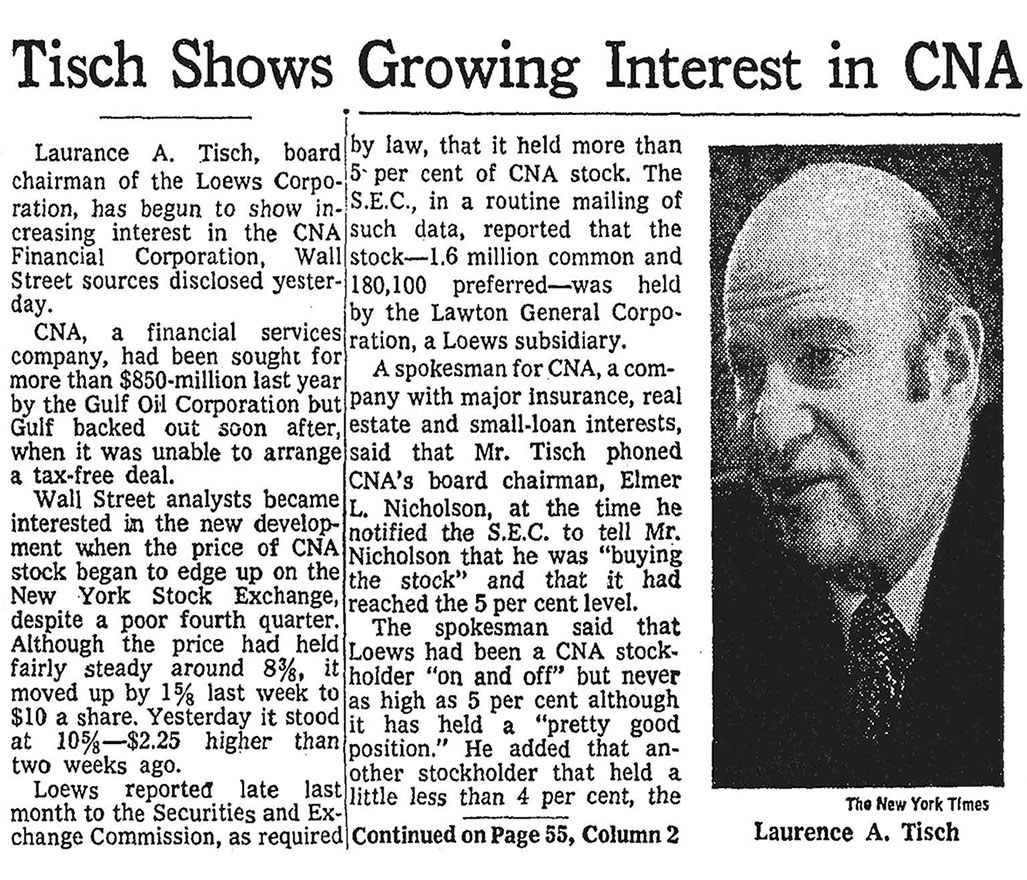

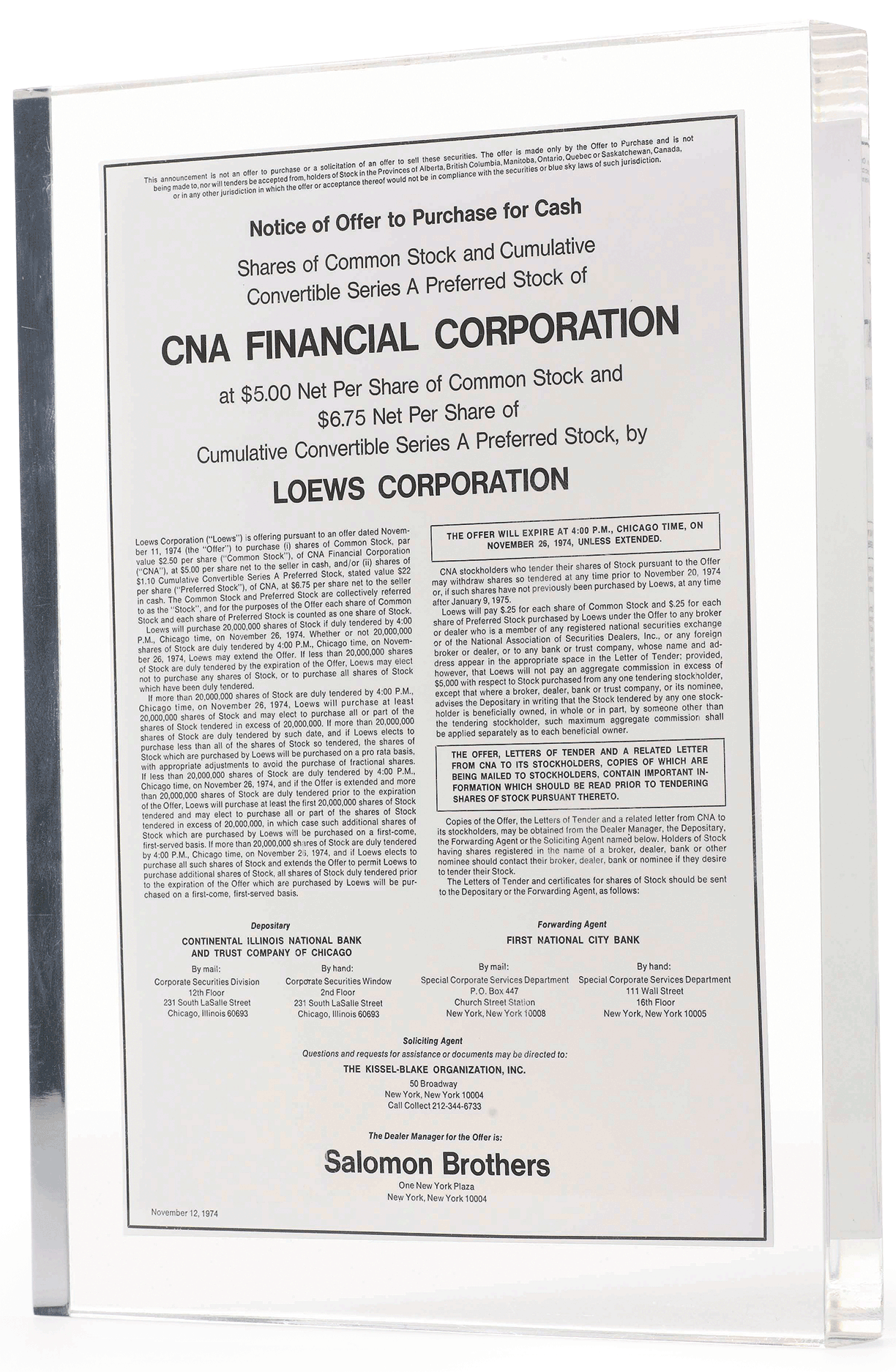

Larry Tisch’s hostile bid for CNA drew attention from Wall Street and the media. Most observers believed the Loews tender offer would fail.

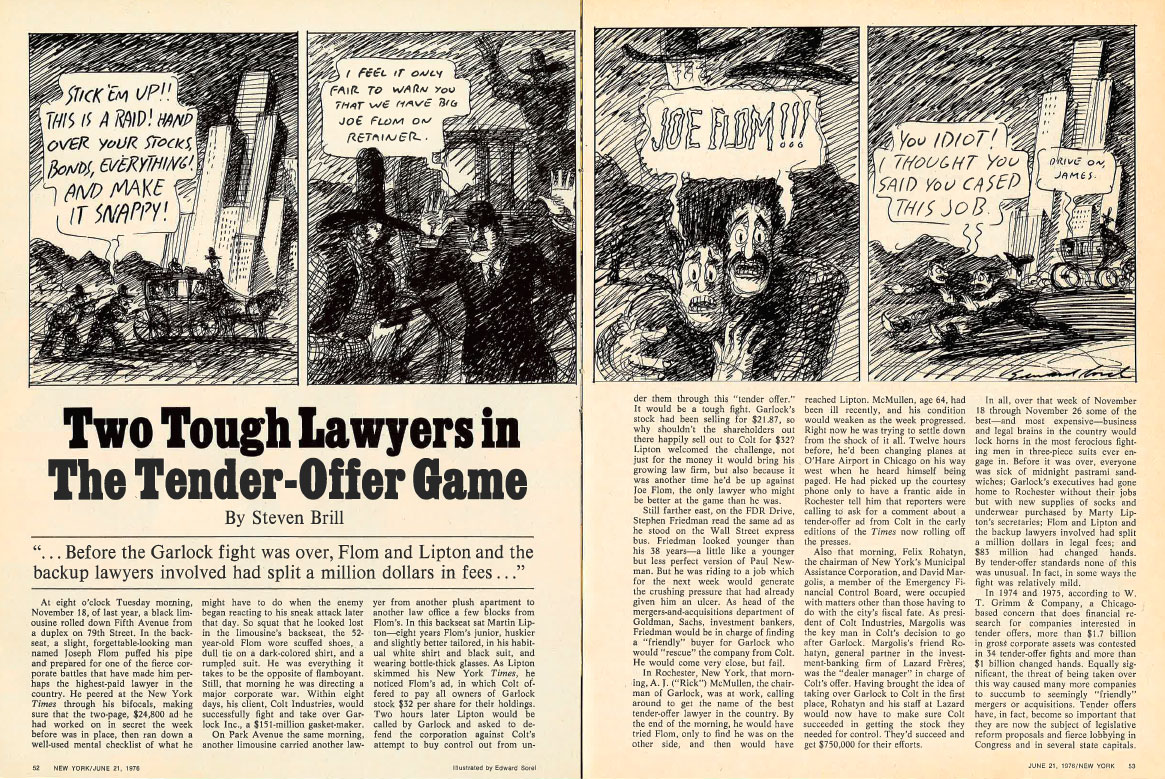

That expansion was also fueled by the close relationship that Lipton and Wachtell Lipton developed with Salomon Brothers, and in particular Ira Harris, a partner at that investment bank, in helping it with its arbitrage practice. That work helped get the firm involved in helping clients run and defend proxy fights, the technique by which contests for corporate control tended to occur in the 1970s. In that space, Wachtell Lipton shared a niche with another emerging firm, Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher, & Flom, whose key partner Joe Flom was then considered the pre-eminent lawyer in contests for corporate control. Like Skadden, Wachtell Lipton was willing to help clients, either on the defense or insurgent front, in these contests, at a time when more venerable New York firms were not.

The intent of [Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom] was to advance a sound and well-grounded argument for target boards responding to takeovers to protect not just stockholders, but the company’s full range of stakeholders.

Although Lipton later became primarily known for his work defending against corporate takeovers — with Flom being more associated with bidders — it was Lipton’s work for a hostile bidder, Loews Corporation, that he credits with markedly increasing Wachtell Lipton’s profile and in the field of mergers and acquisitions. Working with Ira Harris of Salomon Brothers, Wachtell Lipton helped Loews and its CEO, Laurence Tisch, prevail in a year-long struggle to acquire CNA Insurance Company, which was represented by Joe Flom. This was in an era when such struggles were rare. The contest received high-profile media coverage, and resulted in major companies and investment banks looking to Lipton and his firm for advice on takeover matters. As a 1976 New York magazine article, “Two Tough Lawyers in the Tender-Offer Game,” about Flom and Lipton put it:

Lipton and his law firm of Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz are newer to the tender game, having taken the plunge in 1973. Beyond its reputation for being overwhelmingly partial to NYU students, Wachtell is also known at top law schools as one of the few firms that pay starting lawyers more than the “going rate” paid by the Wall Street firms. (This year, the rate is $22,500.) Wachtell Lipton is far less dependent than Skadden, Arps is on tender offers for its income. Its general litigation, securities, and antitrust departments are highly respected and kept busy, and Lipton himself is so highly regarded in all areas of securities work that he’s frequently been talked about as a future SEC chairman. Nonetheless, Lipton has been increasingly involved in tender fights and enjoys the distinction of having won the most grueling fight of all — in which Loews finally took over CNA in a battle that lasted nine months and was complicated by six state insurance statutes and a bitter political and publicity fight waged by a CNA management that simply wouldn’t let go.13

Over a nine-month period in 1974, Wachtell Lipton successfully represented Loews Corporation in its tender offer for CNA, establishing the firm in the takeover arena.

Throughout most of the 1970s, Wachtell Lipton was as likely to represent those making hostile tender offers as those resisting them. Lipton himself used his firm memos, articles, speeches, and testimony before regulators to express concern about impediments to tender offers, and put out guidance for bidders explaining the techniques most likely to help them successfully acquire their targets.14 In fact, Lipton’s view at this early time was that if the federal government took action, along the lines of the rules in the London City Takeover Code — which required all-shares bids and equal treatment of all investors — then takeover defenses under state law should be preempted as interfering with the right to make a tender offer under the Williams Act, and that corporate boards and management should be chary about opposing offers to their stockholders without a strong reason to do so.15 In general, Lipton was skeptical in this period about management efforts to impede all-shares tenders offers, believing that with the help of arbitrageurs, who he had been representing for several years, and other market players, ordinary stockholders could make good decisions and that arbitrageurs would take the worst risks.16 Building on his deep M&A experience, in 1976, Lipton co-authored a detailed treatise on M&A law for the American Bar Association’s National Institute on Takeovers, a work that was eventually published as Takeovers and Freezeouts in 1978.17

At the same time, because Flom was becoming the lawyer of choice for the most common bidders for control — and the most assertive investment bank, Morgan Stanley, then pushing hostile tender offers — Lipton and Wachtell Lipton continued to get defense-side representations. That feature of the practice grew even more as Wachtell Lipton’s relationship with Goldman Sachs, the leading M&A defense investment bank, deepened. One of these engagements was to change his practice, and his thinking about takeover law, in a profound way.

The McGraw-Hill Takeover Defense and Its Effect On Lipton’s Embrace of Stakeholder Corporate Governance

At the end of 1978, Lipton and Wachtell Lipton then took on a matter that would profoundly change his perspective on hostile takeovers, and corporate law more broadly. The CEO of McGraw-Hill, and descendant of the founders, Harold McGraw, begged Lipton to defend his company against a hostile bid from American Express. Lipton was reluctant because his small firm of lawyers was exhausted and had even scheduled two weeks of time off for everyone at the firm. But McGraw impressed upon Lipton how serious the threat was to his company’s employees and its tradition of excellence, and Lipton relented. Wachtell Lipton then embarked on a wide-ranging defense strategy, which involved using the media to cast American Express’s motives in a bad light and to make plain what the bid’s implications were for McGraw-Hill’s employees and customers. The firm filed regulatory complaints to block the deal, and sued in the New York Supreme Court. Eventually, American Express, which had been advised by Joe Flom and Morgan Stanley, gave up without purchasing any shares.

In June 1976, New York magazine depicted Lipton and fellow attorney Joe Flom as bitter rivals in corporate takeover battles.

This experience with Harold McGraw to defend the company his family had created was transformative for Lipton, as Lipton explained:

Harold thought that the company was worth far more than [the] $34 per share [Amex offered] and would achieve that value in just a few years. But even more important than the money, Harold spoke about the culture and integrity of McGraw-Hill, its independence, and its leadership role in publishing and media. He thought all of these critical attributes would be lost by an American Express takeover . . . The board of directors agreed . . . For Harold it was not about money. It was about the employees and the independence and integrity of the publications; it was about credibility and morality. McGraw-Hill must not lose its independence.18

Harold McGraw (pictured above) convinced the firm to take on the defense of the company that bore his family’s name.

As a result of his experience working to defend McGraw-Hill, Lipton came to see the larger implications of takeovers more clearly. In the course of developing arguments to help McGraw defend the company he created, Lipton began to embrace them as a personal belief system. That was especially so in terms of the idea that corporations’ value to society could not be reduced solely to how much profit they delivered to their stockholders. Protecting employees who had had given years to the company, preserving a legacy of quality for consumers, and honoring commitments to corporate communities struck Lipton as entirely proper goals when responding to a takeover. This experience defending McGraw was inspirational in another key way. Because so much of the law of takeover defense was undecided, Wachtell Lipton had given opinions to and made arguments for McGraw-Hill with less than ideal support in traditional statutory and case law. To fill that gap for his burgeoning defense practice,19 Lipton then wrote his now-iconic 1979 article, “Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom,”20 using the firm’s legal opinions to the McGraw-Hill board as the first draft.21 The intent of the article was to advance a sound and well-grounded argument for target boards responding to takeovers to protect not just stockholders, but the company’s full range of stakeholders. And as an important practical matter, the article served to encourage courts to embrace its arguments, and create a body of case law that followed it and could be used to defend takeover targets. But, unlike the typical article, this one caused a firestorm among legal practitioners, and business and law school professors. As Lipton recalled its origins:

[When we were defending the AMEX takeover bid,] the McGraw-Hill board of directors really pressed us on the business judgment rule. When a client presses you on a legal opinion, you really want to research it carefully. And we had been researching this issue for years. But we had really failed to find a case directly on point. Most of the academic writing up to that point was that this was something the shareholders should decide, not management, not the board of directors. But we gave an opinion, an absolute opinion. And I used the opinion in that case to write an article called ‘Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom.’”22

McGraw-Hill would shock the business world for spurning American Express’s initial offer of $830 million and calling it “illegal, unsolicited, and improper.

Lipton Creates An Intellectual Framework Justifying Takeover Defense: Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom

Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom, 35 Bus. Law. 101 (1979), was a ground-breaking statement of the case for takeover defense by target company boards of directors. In it, Lipton marshaled the legal and policy arguments in favor of the authority of boards of directors to reject and actively oppose unsolicited takeover bids. Writing at a point in time when takeover activity was accelerating but judicial treatment of the proper role of target directors was nascent, Lipton framed the subject in elemental terms:

It would not be unfair to pose the policy issue as: Whether the long-term interests of the nation’s corporate system and economy should be jeopardized in order to benefit speculators interested not in the vitality and continued existence of the business enterprise in which they have bought shares, but only in a quick profit on the sale of those shares? The overall health of the economy should not in the slightest degree be made subservient to the interests of certain shareholders in realizing a profit on a takeover. Even if there were no empirical evidence that refuted the argument that shareholders almost always benefit from a takeover (as noted below, the empirical evidence is to the contrary) and even if there were no real evidence, but only suspicion, that proscribing the ability of companies to defend against takeovers would adversely affect long-term planning and thereby jeopardize the economy, the policy considerations in favor of not jeopardizing the economy are so strong that not even a remote risk is acceptable.23

Lipton’s conclusions were crisply stated:

- Directors should not be forced to accept any takeover bid that is at a substantial premium and the usual rule that directors may accept or reject a takeover bid if they act on a reasonable basis and in good faith should continue.

- Takeover bids are not so different from other major business decisions as to warrant a unique sterilization of the directors in favor of direct action by the shareholders.24

The overall health of the economy should not in the slightest degree be made subservient to the interests of certain shareholders in realizing a profit on a takeover.

Lipton’s advocacy for takeover defense rested on several pillars. Perhaps most fundamental was the then-bold claim that the directors’ statutory authority to manage the corporation’s “business and affairs” encompassed takeover bid decision-making.25 This was bold because under federal law, tender offers were directed solely to stockholders, and the target board had no approval right. Lipton argued that any transaction that could change control of a corporation was a proper subject for board action, and that boards had to step up and protect the corporation if a tender offer threatened the bests interests of the corporation and all of its stakeholders, not just the stockholders. Otherwise, “Executives, employees, customers, suppliers and others dependent on doing business with the company would have no assurance of continuity.”26

Lipton also relied on real world data to attempt to buttress his argument. Citing to the 36 unsolicited tender offers defeated by the target company in the 1973-1979 period, Lipton noted that the shares of over 50 percent of the targets were either trading at a higher market price than the rejected offer price or were acquired after defeat of the tender by another company at a higher price.27 Going further, Lipton posited (a) that “[t]he proper comparison is not between the price of the stock in the market at the rejected offer price, but between the rejected offer price and the amount that could be obtained otherwise upon the sale of the entire company”; (b) by the same token, that stockholders were never damaged by rejection of a takeover bid since the “true value” of the target remained undamaged by rejection of a takeover bid; and (c) citing an unpublished Goldman Sachs study, that in 95 percent of the cases where a company was acquired after an initial resistance to a takeover bid, the stockholders received a higher price than the original offer.28

This is how the first page of Lipton’s influential article, Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom, appeared when it came out in the Business Lawyer in 1979.

Takeover Bids also treated, and rejected, the view that stockholder acceptance of a tender offer was a reliable barometer of the offer’s merits, owing to “the special dynamics of a tender offer”:29

In sum, an unsolicited tender offer is often successful not because a majority of the shareholders of the target determine that it is a good acquisition, but because the dynamics of a tender offer trigger motivations by different minority segments of the shareholder body, such as those who:

- believe that once the raider gets control it will probably move to obtain 100% ownership and it is unlikely that they will be able to realize any more for their shares than the takeover price;

- need to show performance;

- desire to avoid a loss of market liquidity;

- believe that the raider is not a good manager;

- desire not to be a minority shareholder in a controlled company;

- have a tax incentive to sell;

- fear poor treatment on a second step freeze out by the raider;

that in aggregate creates an ad hoc consortium of sellers of a majority of the shares of the target.30

Lipton’s argument that tender offers had an intrinsically coercive effect in comparison to stockholder votes on a merger — where a stockholder can freely vote no understanding she can receive the merger premium if the other stockholders vote yes in sufficient numbers — was one later adopted by some scholars, like Lucian Bebchuk,31 who otherwise differed from Lipton’s view that boards of directors, rather than stockholders, should ultimately decide on whether a takeover should occur.

That point made, the case for takeover defense was based on the more fundamental level of the “necessity” of long-term planning and consideration of all the corporation’s constituencies:

Even in the face of such an ad hoc consortium, the necessity from technological, social and economic standpoints for long-term planning by business requires a policy decision in favor of not mandating decisions that ignore or penalize long-term planning. Rather than forcing directors to consider only the short-term interests of certain shareholders, national policy requires that directors also consider the long-term interests of the shareholders and the company as a business enterprise with all of its constituencies in addition to the short-term and institutional shareholders.32

In what would be an issue he would have to confront more directly in coming years, Lipton was equivocal, if indeed not skeptical, that a corporate board could block a takeover bid solely because the board thought the price was too low and not because there was some other threat to a corporate stakeholders, such as its workers or consumers, stating:

Where the only issue in a tender offer is price, our present legal structure permits a raider, after compliance with the applicable federal and state laws, to short-circuit acceptance by the directors of the target and to make its offer directly to the shareholders of the target. The shareholders then have the power, independent of the directors, to determine whether or not to accept the offer. Even under the most far-reaching of the state takeover statutes, no tender offer has been blocked on the question of price. The decisions are uniform that where there is a cash tender offer, the state will not determine what is a fair premium but will leave that determination to the shareholders. If that is the law and that is what happened, why the issue? Primarily, because price is rarely the only issue.33

Recognizing the potential for conflicts between management’s self-interest in preserving the independence of a target company and the directors’ decision to accept or reject a takeover bid, Lipton advocated the following best practices:

- Management (usually with the help of investment bankers and outside legal counsel) should make a full presentation of all of the factors relevant to the consideration by the directors of the takeover bid, including:

- historical financial results and present financial condition;

- projections for the next two to five years and the ability to fund related capital expenditures;

- business plans, status of research and development and new product prospects;

- market or replacement value of the assets;

- management depth and succession;

- can a better price be obtained now;

- timing of a sale; can a better price be obtained later;

- stock market information such as historical and comparative price earnings ratios, historical market prices and relationship to the overall market, and comparative premiums for sale of control;

- impact on employees, customers, suppliers and others that have a relationship with the target;

- any antitrust and other legal and regulatory issues that are raised by the offer; and

- an analysis of the raider and its management and in the case of a partial offer or an exchange offer pro forma financial statements and a comparative qualitative analysis of the business and securities of both companies.

- An independent investment banker or other expert should opine as to the adequacy of the price offered and management’s presentation.

- Outside legal counsel should opine as to the antitrust and other legal and regulatory issues in the takeover and as to whether the directors have received adequate information on which to base a reasonable decision.

- If a majority of the directors are officers or otherwise might be deemed to be personally interested, other than as shareholders, a committee of independent directors, although not in theory necessary, from a litigation strategy standpoint may be desirable. The exigencies and pressures of a takeover battle are such that it is desirable to avoid proliferation of committees, counsel and investment bankers. The target will be best served if it is advised by one investment banker and one outside law firm.

- It is reasonable for the directors of a target to reject a takeover on any one of the following grounds:

- inadequate price;

- wrong time to sell;

- illegality;

- adverse impact on constituencies other than the shareholders;

- risk of nonconsummation;

- failure to provide equally for all shareholders; and

- doubt as to quality of the raider’s securities in an exchange offer.34

In this section of the article, Lipton began to embrace a more assertive role for independent directors and advisors. At this stage, he argued that takeovers did not present a direct conflict of interest requiring the recusal of the management directors — especially given that he was writing before the advent of management buy-outs — but he referred frequently to the independent directors and ensuring that they had financial and legal advice independent of management, and that the board as a whole, and not management in isolation, was the instrument that would determine how the company reacted to the takeover offer.

One year after Takeover Bids, Lipton published an update, Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom: An Update After One Year, 36 Bus. Law. 1017 (Apr. 1981). Lipton there catalogued the judicial authorities and commentators that had aligned with the Takeover Bids position:

- Panter v. Marshall Field & Co., 646 F.2d 271 (7th Cir. 1981).

- Johnson v. Trueblood, 629 F.2d 287 (3d Cir. 1980).

- Treadway Co., Inc. v. Care Corp., 638 F.2d 357 (2d Cir. 1980).

- Crouse-Hinds Co. v. InterNorth, Inc., 518 F. Supp. 416 (N.D.N.Y. 1980).

- Arthur Fleischer, Tender Offers: Defenses, Responses and Planning (1980).

- Harold M. Williams, Chairman of the S.E.C., Tender Offers and the Corporate Directors (Jan. 17, 1980) (albeit requiring a special committee of directors in every case)35

As doubtless expected, Takeover Bids drew considerable critique — both promptly and in the debate of its core ideas that has continued unrelentingly. Perhaps the most notable early voices on the opposite side of the debate were then-Professors Frank Easterbrook and Daniel Fischel, who argued in response to Lipton that “current legal rules allowing the target’s management to engage in defensive tactics in response to a tender offer decrease shareholders’ welfare.”36 Easterbrook and Fischel urged that the proper management response to an unsolicited tender offer was passivity: “management should not propose antitakeover charter or bylaw amendments, file suits against the offeror, acquire a competitor of the offeror in order to create an antitrust obstacle to the tender offer,37 buy or sell shares in order to make the offer more costly, give away to some potential ‘white knight’ valuable corporate information that might call forth a competing bid, or initiate any other defensive tactic to defeat a tender offer.” Their conclusion: “shareholders’ welfare is maximized by an externally imposed legal rule severely limiting the ability of managers to resist a tender offer even if the purpose of resistance is to trigger a bidding contest.”38 Responding directly to some of the points advanced in Takeover Bids, Easterbrook and Fischel argued that Lipton was “simply wrong in concluding that takeovers injure the long-term interests of the corporate system and economy” since (they asserted) a successful long-term plan “will be reflected in higher share prices that discourage takeovers.”39 More fundamentally, they challenged Lipton’s premise of a target’s duty to consider the interests of “noninvestor groups such as employees, customers, creditors, and the community in general” as “deeply flawed” — contending that because “[t]akeovers improve economic efficiency” and “that improvement usually enhances the position of those who deal with the firm.”40 Lipton’s approach, the then-professors argued, “amounts to rejection of the idea that agents (managers) are accountable to their principals (shareholders)”; and by allowing management to sacrifice shareholder interest to those of noninvestor groups, “far more than the separation of ownership and control or any other characteristic of the modern corporation, would greatly prejudice shareholders by decreasing the incentive of management to act in their best interest.”41

In a follow-up writing in the Business Lawyer, Easterbrook and Fischel elaborated on their critique of Lipton’s position.42 There they identify the source of their differences as springing from “the treatment of fundamental economic issues” — namely, their views that Lipton was wrong in contending that his approach was in the shareholders’ interests. In support of that critique, the then-professors argued that it was “implausible” to suggest that stock is priced in the market at less than its “true value,” since they “assume that markets are indeed efficient”; that it is “futile” to expect that shareholders could monitor managers’ performance; that shareholders are “unambiguously worse off” if defensive tactics preserve corporate independence.43 On a doctrinal level, their argument against application of the business judgment rule to defensive tactics was rested on the premise that managers have “acute conflicts of interests” in resisting takeovers, and their view that “shareholder’s welfare is maximized by a binding legal rule requiring managers to acquiesce when confronted with a tender offer.” Lipton’s recommendation that target company boards consult with legal and financial experts in determining whether to oppose a takeover bid was derided as “sheer waste” while “no doubt lucrative for the various outside professionals involved”; under the then-professors’ view, the target’s board “should relax, not consult any experts, and let the shareholders decide.”44

I felt I was involved in a process…that was not good for the economy, not good for the people involved, and I developed a very, very strong bias against doing bust-up deals.

This debate was featured not only in academic journals, but also in the New York Times. In response to Easterbrook and Fischel’s article “When Shareholders Become the Victim,”45 Lipton wrote back with “Boards Must Resist.”46 Lipton noted that the Easterbrook and Fischel model of passivity was a “drastic change from the current law,” and cited academic research to suggest that short-termism by management “may lead to an unwillingness to assume the risks inherent in planning for long-term profits, which ultimately is socially and economically damaging.” Lipton concluded that it was in the shareholders’ best interests that the board of directors assess a takeover offer on its merits and reject it if deemed insufficient, rather than acquiescing to all takeover offers.

Professor Ronald Gilson also joined the debate in May 1981 with his article A Structural Approach to Corporations: The Case against Defensive Tactics in Tender Offers.47 Gilson argued for a more limited role for management in blocking a tender offer, asserting that the market “is the best unbiased estimate of the value of a corporation’s stock. If target management prevents shareholders from responding to an offer, that valuation process is bypassed.” 48 In contrast to Lipton’s view of the primary role of the board of directors in accepting or blocking a tender offer, Gilson saw the board of directors as aiding the shareholders in making the decision through providing the shareholders with information or bargaining on behalf of the shareholders which may involve looking for a white knight. The “obvious and inherent conflict of interest between management and shareholders,” Gilson posited, led to corporate law’s resolution of the conflict by focusing on management’s motive in defeating the tender offer; that approach (he argued) is inadequate not only because of the uncertainties of motivational analysis, but because it fails to address the “structural” question of whether management should be able to act “at all.”49 Gilson’s construct was that as a general “principle” “shareholders must make tender offer decisions.”50 In Gilson’s view, the tender offer was “the critical mechanism through which the corporate structure imposes constraints on certain forms of managerial self-dealing,” while management-adopted defensive tactics could make tender offers impossible — which (in his view) was “flatly inconsistent with the structure of the corporation.”51 Gilson’s conclusion: “Defensive tactics, because they alter the allocation of tender offer responsibility between management and shareholders contemplated by [the structure of the modern corporation], are inappropriate.”52

As to Takeover Bids’ claim that target shareholders benefit from management discretion to block takeover bids, Gilson responded that Lipton’s analysis failed to account for general price movements or to discount future value to present values, and that other “more careful empirical studies” were “flatly inconsistent with Lipton’s conclusions.”53 But more importantly, Gilson’s rejoinder was that “[c]apital market theory” teaches that the market is “the best unbiased estimate of the value of a corporation’s stock.”54 And as to the contrary argument justifying defensive tactics by responsiveness to “nonshareholder constituencies,” Gilson argued that “social responsibility” actions are “a specialized class of suboptimization” by management that courts cannot effectively regulate and which “the structure of the corporation relies upon the tender offer process to control.”55 In short: “there is nothing about management’s social judgments which renders them more sacrosanct than management’s business judgments.”56 Management’s proper function, in Gilson’s construct, would be limited to aiding the shareholders in making the tender offer decision — passing information, and also a “bargaining role” in looking for a white knight (a departure from the total passivity role advocated by Easterbrook and Fischel). In his concluding section, Gilson argued that courts deciding takeover cases should look to something like the system then prevailing in the U.K. Under the City Takeover Code (which was not even official government policy but which all participants in the U.K. adhered to). Under that system, a fully funded, unconditional, all-shares bid could not be “frustrated” by the target’s board.57 Gilson viewed that as a good system.

But that thesis, as succeeding years would show, ignored a problem with that analogy. Under U.S. law as of that time, a tender offer did not have to be for all shares, and a tender offer could offer different prices for the initial bloc of shares tendered, and lower or different consideration for shares acquired in the second tier. For the reasons Lipton had explained, this placed stockholders in the position of being coerced into tendering into the front-end, to avoid receiving only the lower, back-end consideration. As of this time in the American public markets, no protection against this sort of coercion existed under the securities laws. Lipton, as will be seen, used this developing bidder tactic as additional ballast for his argument that boards of directors not only had the duty to make sure that other opportunities that could provide higher value were explored (a duty that Gilson accepted as valuable to stockholders), but to protect stockholders against structurally coercive tender offers.

Not surprisingly, the controversy ignited by Lipton’s Takeover Bids over the proper scope of defensive tactics, and the proper legal and judicial response, continued for years — as it was not until 1985 that the question came to decision by the Delaware Supreme Court in the trio of Unocal, Moran, and Revlon. The additional leading commentary during the interim included:

- Leo Herzel, John R. Schmidt & Scott J. Davis, Why Corporate Directors Have a Right to Resist Tender Offers, 3 Corp. L. Rev. 107 (1980);

- Martin Lipton, Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom: A Response to Professors Easterbrook and Fischel, 55 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1231 (1980);

- Frank H. Easterbrook & Daniel R. Fischel, Takeover Bids, Defensive Tactics, and Shareholders’ Welfare, 36 Bus. Law. 1733, 1733 (1981);

- Lucian A. Bebchuk, The Case for Facilitating Competing Tender Offers, 95 Harv. L. Rev. 1028, 1029, 1054 (1982);

- Lucian A. Bebchuk, The Case for Facilitating Competing Tender Offers: A Reply and Extension, 35 Stan. L. Rev. 23 (1982);

- Frank H. Easterbrook & Daniel R. Fischel, Auctions and Sunk Costs in Tender Offers, 35 Stan. L. Rev. 1 (1982) (opposing auctions as well as outright defense);

- Ronald J. Gilson, Seeking Competitive Bids Versus Pure Passivity in Tender Offer Defense, 35 Stan. L. Rev. 51 (1982);

- David P. Baron, Tender Offers and Management Resistance, 38 J. Fin. Econ. 331, 342 (1983);

- Louis Lowenstein, Pruning Deadwood in Hostile Takeovers: A Proposal for Legislation, 83 Colum. L. Rev. 249 (1983);

- Karoly Sziklas Gutman, Tender Offer Defensive Tactics and the Business Judgment Rule, 58 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 621 (1983);

- S.E.C. Advisory Committee on Tender Offers, Report of Recommendations, 70-106 (July 8, 1983) (statement of Easterbrook and Jarrell); and

- Frank H. Easterbrook & Gregg A. Jarrell, Do Targets Gain From Defeating Tender Offers, 59 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 277 (1984).

Back to the Boardroom: Lipton Puts His Ideas About Takeover Practice Into Practice

After Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom, Lipton and Wachtell Lipton found themselves literally on the defense. For one thing, Joe Flom and Skadden had the best stable of the new breed of corporate takeover bidders. For another, the article led to Lipton and Wachtell Lipton having to respond to critics of the article’s position. This made it more difficult for Wachtell Lipton to credibly represent bidders who might want to take a position contrary to the article’s basic arguments.58 More pragmatically, the reality of a hostile bid is that there are at least two sides, and Wachtell Lipton was flooded with requests for help from corporations targeted by raiders. As Wachtell Lipton became intensively involved in coming up with creative techniques for addressing legally novel situations, the firm viewed it as unwise to take on matters where loyalty to the bidder-client might require arguing that actions the firm had recommended might be invalid under statute or be found a breach of fiduciary duty. As a personal matter, Lipton viewed the type of hostile offers of the period — which often involved an implicit willingness of the bidder to go away for a payment to itself, so-called “green mail,” a coercive two-tiered front-end loaded bid stampeding stockholders into acceptance, partial offers for only a majority of the shares, and plans to dismantle and leverage up the target — as harmful to society. “I felt I was involved in a process…that was not good for the economy, not good for the people involved, and I developed a very, very strong bias against doing bust-up deals.”59

Joseph Flom (left) and Martin Lipton (Right). The “rivals,” in fact, were friends and met periodically for many years to have breakfast together.

In the early 1980s, Lipton was successful in persuading courts that boards could actively resist takeovers that they opposed. But he and his target-side clients had a more market-based problem. The defensive arsenal available to targets was limited, and unattractive. Many of the available tools that targets deployed had a “we had to burn the village to save it” quality, in which the target would engage in some different form of leveraging or busting up the company than the original bidder proposed, or simply sold the company to another higher bidder. Defensive strategies of this kind were naturally seen as unsatisfying and ultimately unsuccessful by Lipton and those who embraced his views. These realities, and the undeniable and unrelenting desire of institutional investors to tender into premium bids, led Lipton to think creatively about a defensive measure that would allow directors to effectively resist hostile bids in a way that did not inflict harm on the company.60

1 Robert Slater, Mercenaries of the Takeover Game: Joseph Flom & Martin Lipton, in The Titans of Takeover 145, 151 (1987).

2 Dan Slater, Partner for Life, N.Y.U. L. Mag., Fall 2013, at 30.

3 Slater, Partner for Life, at 30. For a recent recollection of Lipton about this time in his life,see Jessica C. Pearlman, Interview with Marty Lipton, 75 Bus. Law. 1709, 1709-11 (2020).

4 Slater, Partner for Life, at 29.

5 Martin Lipton, My 64 Years at NYU – 1952-2016 1 (2016).

6 Martin Lipton, Collected Quotations (2021).

7 Hoffer Kaback, Martin Lipton: For the Defense, Directors & Boards, Summer 1999.

8 Martin Lipton, Collected Quotations (2021).

9 Timothy Harper, A Boardroom Lawyer, Super Law. Mag. – N.Y. Metro, 2013, at 20.

10 Slater, The Titans of Takeover, at 152.

11 Slater, The Titans of Takeover, at 153.

12 Slater, The Titans of Takeover, at 152.

13 Steven Brill, Two Tough Lawyers in the Tender-Offer Game, N.Y. Mag. (June 21, 1976), 52-61; see also, Pearlman, 75 Bus. Law. at 1723.

14 See, e.g., Beneficial Ownership, Takeover and Acquisitions by Foreign and Domestic Persons: Proceedings Before the Securities & Exchange Commission 151-52 (Nov. 14, 1974) (statement of Martin Lipton) (opens by arguing that tender offers should not be impeded, that they provide valuable liquidity, and that they are the only “practical way that has evolved for changing control . . . Essentially what we are talking about is if the management of a corporation is not doing a good job, the company is under valued at the market or the assets of the company are not being profitably employed, the company becomes vulnerable to takeover by tender offer… [I]t is quite obvious from the current popularity of cash tender offers that this is a means of acquisition of control of other companies that is acceptable.”). See also Memo: Untitled (Mar. 11, 1974).

15 Beneficial Ownership, Takeover and Acquisitions by Foreign and Domestic Persons, at 151-62, 206; see also Martin Lipton, Recent Books, 72 Mich. L. Rev. 358, 360 (1973-1974) (review of a book on tender offers in which Lipton refers to decisions under the Williams Act that have made it an “almost impossible barrier to contested takeovers.” This article also refers to “one member of the New York Bar who has become so renowned for his successful defense against takeovers that the first question on Wall Street is which side has him.” Lipton, Recent Books, at 360.(Lipton is not referring to himself, but Joe Flom.))

16 Beneficial Ownership, Takeover and Acquisitions by Foreign and Domestic Persons, at 183. In fact, before Lipton developed guidance for takeover targets, he developed a checklist for those making a hostile tender offer for control. Martin Lipton & Erica H. Steinberger, Cash Tender Offers, in Takeovers & Takeouts 9, 9-107 (1976); see also Martin Lipton & Erica H. Steinberger, Introduction, 23 N.Y. L. Sch. L. Rev. 375 (1978), (introduction in which the authors discuss the fact that state takeover laws have been impinging on the ability to use tender offers for acquisitions and look favorably on the possibility they will be struck down as unconstitutional); see also,The Southwestern Legal Foundation,Symposium Securities Regulation Corporate & Tax Aspects of Securities Transactions (Apr. 28, 1977) (providing similar perspectives).

17 Martin Lipton & Erica H. Steinberger, Takeovers & Freezeouts (1978).

18 Martin Lipton, Remarks at the Memorial Service for Harold W. McGraw, Jr. 4-5 (Apr. 16, 2010).

19 Pearlman, 75 Bus. Law. at 1713 (“By 1979, I was – if not 100 percent, 99.9 percent involved in defending against hostile takeovers.”).

20 Martin Lipton, Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom, 35 Bus. Law. 101 (1979).

21 Lipton, Remarks at the Memorial Service for Harold W. McGraw, Jr., at 6; Slater, The Titans of Takeover, at 157; Living Legends: Martin Lipton Meets Andrew Ross Sorkin (Introduced by Chancellor Leo Strine), 14 M&A J. 8, 11 (Apr. 20, 2014); Pearlman, 75 Bus. Law. at 1712-13.

22 The Deal Staff, Martin Lipton and the Dark Arts of Defense, The Deal Pipeline (Apr. 8, 2016); see also Pearlman, 75 Bus. Law. at 1714; Lipton, Remarks at the Memorial Service for Harold W. McGraw, Jr., at 6.

23 Lipton, 35 Bus. Law. at 105.

24 Lipton, 35 Bus. Law. at 103-04.

25 Lipton, 35 Bus. Law. at 104 n.10.

26 Lipton, 35 Bus. Law. at 110.

27 Lipton, 35 Bus. Law. at 106-09.

28 Lipton, 35 Bus. Law. at 108.

29 Lipton, 35 Bus. Law. at 113.

30 Lipton, 35 Bus. Law. at 115.

31 Lucian A. Bebchuk, Toward Undistorted Choice & Equal Treatment in Corporate Takeovers, 98 Harv. L. Rev. 1693 (1985).

32 Lipton, 35 Bus. Law. at 115.

33 Lipton, 35 Bus. Law. at 116-17.

34 Lipton, 35 Bus. Law. at 121-23.

35 Lipton, 36 Bus. Law. at 1017-23.

36 Frank H. Easterbrook & Daniel R. Fischel, The Proper Role of a Target’s Management in Responding to a Tender Offer, 94 Harv. L. Rev. 1161, 1164 (1981).

37 Easterbrook & Fischel, 94 Harv. L. Rev. at 1201.

38 Easterbrook & Fischel, 94 Harv. L. Rev. at 1164; see also 94 Harv. L. Rev. at 1181 n.51 (referring to the template form of target company board minutes included in Takeover Bids as an “elaborate script for camouflaging the target’s reasons for resisting an offer”).

39 Easterbrook & Fischel, 94 Harv. L. Rev. at 1183-84.

40 Easterbrook & Fischel, 94 Harv. L. Rev. at 1190.

41 Easterbrook & Fischel, 94 Harv. L. Rev. at 1191-92.

42 Frank H. Easterbrook & Daniel R. Fischel, Takeover Bids, Defensive Tactics, & Shareholders’ Welfare, 36 Bus. Law. 1733 (1981).

43 Easterbrook & Fischel, 36 Bus. Law. at 1734-35, 1736, 1737.

44 Easterbrook & Fischel, 36 Bus. Law. at 1749-50.

45 Frank H. Easterbrook & Daniel R. Fischel, When Shareholders Become the Victims, N.Y. Times, July 12, 1981, https://www.nytimes.com/1981/07/12/business/business-forum-when-shareholders-become-the-victims.html.

46 Martin Lipton, Boards Must Resist, N.Y. Times, Aug. 9, 1981.

47 Ronald J. Gilson, A Structural Approach to Corporations: The Case Against Defensive Tactics in Tender Offers, 33 Stan. L. Rev. 819 (1981).

48 Gilson, 33 Stan. L. Rev. at 858.

49 Gilson, 33 Stan. L. Rev. at 819-20.

50 Gilson, 33 Stan. L. Rev. at 876.

51 Gilson, 33 Stan. L. Rev. at 845.

52 Gilson, 33 Stan. L. Rev. at 848.

53 Gilson, 33 Stan. L. Rev. at 857.

54 Gilson, 33 Stan. L. Rev. at 858.

55 Gilson, 33 Stan. L. Rev. at 864.

56 Gilson, 33 Stan. L. Rev. at 865.

57 Gilson, 33 Stan. L. Rev. at 865.

58 Hoffer Kaback, Martin Lipton: For the Defense, Directors & Boards, Summer 1999.

59 Robert Slater, Mercenaries of the Takeover Game: Joseph Flom & Martin Lipton, in The Titans of Takeover 145, 157 (1987).

60 The Deal Staff, Martin Lipton and the Dark Arts of Defense, The Deal Pipeline (Apr. 8, 2016).