The 1980s Takeover Era and Lipton’s Stockholder Rights Plan

Short-Termism and the Takeover Era

The principles espoused in Takeover Bids formed the foundation for the takeover battles of the 1980s, and the most important defensive innovation in that era, the stockholder rights plan (colloquially known as the “poison pill”), which was invented by Lipton with colleagues at Wachtell Lipton. The need for the stockholder rights plan and other takeover defenses was inspired by Lipton’s belief that the takeover practices of financial raiders during this period had become abusive and needed to be curbed. But, despite the fame of the poison pill and other defensive tactics, Lipton was not against all takeover activity:

I believe in the free market. I believe that there should be a free market in corporate control. I do not think that all mergers should be banned. I do not think that bigness is bad. I do not think that our economic and political systems are threatened by concentration of corporate power through takeovers. I do think that very serious corporate takeover abuses have developed in recent years.61

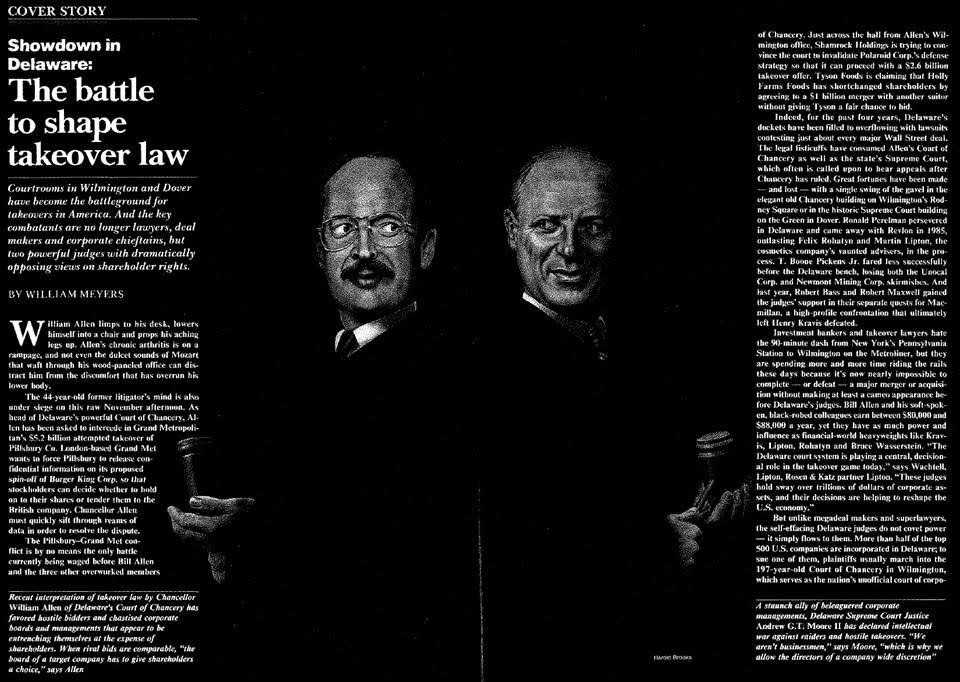

The debate surrounding increasingly widespread use of the pill in takeover defenses of the 1980s inspired this illustration from the Legal Times in 1983.

These takeover abuses arose out of the financialization of takeover activity, as the more traditional friendly strategic merger, which were in fact themselves rare before the 1990s, were replaced by hostile takeovers foisted on target companies involuntarily. These takeovers often involved financial buyers, who used “bootstrap” debt financing to acquire companies, using the target companies’ assets as the security, to pay themselves out lucrative immediate returns, and either dismantling the target companies through sales or leaving them with so much debt that they had to cut their future investment plans, and cut jobs and close plants and other facilities. As Lipton observed, “[s]ignificant changes [had] occurred in the takeover environment in recent months. Prior to 1981 the billion-dollar hostile tender offer was hard to imagine. Now multi-billion dollar bids can readily be financed. Prior to 1981 most bids were any and all cash offers; now the two-tier, front-end loaded offer is the most popular (and the most powerful).”62 The ready availability of multi-billion dollar financing meant that, for the first time, “the size of a company cannot, in and of itself, be considered a defense against a takeover.”63

Lipton warned in Congressional testimony in 1985 that supporting financialized takeovers was “a policy that favors the present at the expense of the future.” But, as Lipton observed, “[u]nfortunately, the future has no political constituency”64:

The situation can be analogized to a farmer who does not rotate his crops, does not periodically let his land lie fallow, does not fertilize his land and does not protect his land by building fences, planting cover, and creating windbreaks. In the early years our farmer will maximize his return from the land. It is a very profitable short-term use. But inevitably it leads to a dust bowl and economic disaster.65

Lipton warned of the dangers of short-termism and saw irony in the failure of government to regulate takeovers despite those dangers:

Long-term planning by business corporations is essential to the future health of our economy, yet in the one area of corporate takeovers, we suffer the strange anomaly of the Government through the SEC arguing that all that counts is immediate profits to shareholders, that corporations should be subject to bootstrap raids through front-end loaded tender offers, and that corporate directors who seek to do long-term planning and serve the long-term interests of all corporate constituencies should not be protected by the business judgment rule.66

The results of those policies were companies that were highly leveraged and myopic in focus, “which comes at the expense of employees, customers, suppliers, communities in which the companies operate and in the long run the nation’s economy as a whole.”67

Long-term planning by business corporations is essential to the future health of our economy.

Beyond their negative economic effects on the specific target companies and their stakeholders, allowing hostile takeovers motivated by financial engineering, not long-term business considerations, also had a larger systemic effect in Lipton’s view. As Lipton warned in Takeover Bids, if corporate boards faced the constant possibility of being forced to sell, it disrupted their ability to invest and implement business plans focusing on sustainable, socially responsible growth.68 As Lipton observed five years later in 1984, hostile acquisitions “preempt[ed] the ability of the target’s board of directors to determine the desirability, price, form, and timing of a merger of the company, a matter which every state corporation law commits to the hands of the company’s board of directors.”69

By the end of the decade, crafty evolutions of the pill were required to fend off increasingly sophisticated attacks.

In view of these dangers, Lipton advocated throughout the 1980s for legislation, building on the U.K. Takeover Code, to reform what he viewed as abusive takeover tactics.70 But, recognizing the unlikelihood of congressional legislation, Lipton worked to develop a defensive arsenal for boards of directors to deploy themselves to protect their companies. The most powerful form of defensive self-help was to become the stockholder rights plan, later also known more commonly as the “poison pill.”

Origins of the Rights Plan

The stockholder rights plan is the single most important tool developed to make real Lipton’s philosophy that the elected board of a company should control the company’s destiny even when facing a takeover bid. Where Takeover Bids set forth the principles underlying Lipton’s conclusion that boards should remain active decision-makers in the face of a takeover, the stockholder rights plan provided an effective instrument for them to do so.

Although the stockholder rights plan had previously been discussed in internal memoranda, Lipton first put the rights plan on display in a memo to clients dated June 20, 1983.71 Lipton began by reaffirming the values espoused in Takeover Bids in no uncertain terms:

We believe that a corporation has the absolute right to

- have a policy of remaining an independent entity,

- have a policy of refusing to entertain takeover proposals,

- reject a takeover bid,

- take action to remain an independent entity, and

- guarantee its shareholders a right to retain an equity interest in the corporation even if someone is successful in obtaining control and forcing a second-step merger.72

Lipton then identified the core problem: The financialization of takeover activity had created a fundamental disconnect between the corporation’s right to remain independent and resist takeover bids, and its practical ability to do so when faced with the coercive power of a hostile tender offer. Lipton noted that it had “become virtually impossible to defend against the stampeding effect of partial and front-end loaded tender offers and assure all shareholders of fair treatment,” and that the SEC “has not recommended new rules which would redress the imbalance” between independent companies and hostile acquirors.73 Lipton noted that litigation, charter amendments, legislation, counter tender offers, and capitalization changes had been successful to some degree, but that “none of these means has proven to be generally applicable and effective.”74 Lipton also recognized that defensive measures like self-tenders that required companies to leverage up and cut future investment were unsatisfying because they compromised company focus on sustainable growth in similar ways to the bids they were developed to defeat. What was needed was a defense that would do no harm to the company’s value and allow it to proceed with its long-term strategy to create value.

Lipton presented the rights plan as a solution to these problems, and as a way of defending against a bid while doing no harm to the company’s business strategy and balance sheet. From the outset, however, he was clear that the rights plan “does not prevent tender offers and does not prevent a second-step merger after a raider has seized control. All it does is assure fair treatment of all shareholders and the right of those who so desire to continue their equity interest following a takeover.”75 In other words, the right plan fit with Lipton’s belief that the threat to be addressed was not takeovers themselves, but takeover abuses.

“The Plan is simple.”76 Though its effects were powerful, its mechanics were straightforward, reflecting an innovative application of existing corporate finance techniques. The first iteration of the Plan, known as a “flip-over” plan, would distribute a dividend of convertible preferred stock (and later, of purchase rights) to all common stockholders, convertible into “the same (or larger) number of shares of common as are outstanding.” The rights were issued when the bidder, having obtained control of the target, took steps to cash out the remaining stockholders or to otherwise engage in another merger, and would dilute the acquirer substantially in comparison to the other stockholders. Lipton counted the “flip-over” provision as among the “normal boilerplate provisions protecting the conversion rights in the event of a merger or other business combination.”77 When such a merger occurred, “the conversion rights would flip-over to the common stock of the raider and the preferred would be convertible into the common stock of the raider.”78 The dilutive flip-over provision formed the “essence of the Plan” by presenting “a difficult problem to a raider contemplating a hostile tender offer. A raider must think twice about the economics of being faced with the issuance of a significant number of shares of its own common stock.”79 The reason is simple: the flip-over when triggered would seriously dilute the acquirer, and thus strip it of much or all of the value it thought it was purchasing.

The Plan is simple.

Importantly, the original pill did not include a so-called “flip-in” trigger. A flip-in prevented a bidder who wished to acquire a company from exceeding a certain toe-hold (later to be commonly set between 10% and 20%) of the target’s shares without triggering the rights to be issued to other common stockholders, and massive dilution of the bidder. A flip-in, if upheld in court, prevented an acquisition of control in the first instance and blocked even a so-called “creeping” acquisition that might be the first step in a control change. Initially, Lipton was dubious about the validity of a flip-in and did not include it in his first rights plans, a decision that was to be useful later when the validity of the pill faced its most important initial test in the Delaware Supreme Court.80

Sample of a client memo regarding “Poison Pills”.

Recognizing that other defensive tactics had amounted to half-measures at most, Lipton placed great weight on this solution and staked his and Wachtell Lipton’s reputation on its validity, stating that “[w]e have no doubts about the legality of the plan. More important, we are convinced of its efficacy in achieving the objectives referred to above.”81 Two months later, Lipton further emphasized the general applicability of the pill, encouraging companies to consider “implementing the Plan before a takeover situation arises,”82 and providing a “suggested model form” for the plan.83 Lipton also noted that the Plan had been used by three companies trading on the NYSE — Bell & Howell, ENSTAR, and Lenox. Those three pioneer plans had been adopted under “special circumstances,” but Lipton began advocating for companies to adopt plans under ordinary circumstances, before any takeover attempt had begun, foreseeing that business-judgment arguments would be more persuasive if the adoption of the rights plan had been made by the board on a clear day.84

Although Lipton had expressed confidence in the legality of the rights plan, as an innovation, he understood it would be the subject of rigorous testing in court. For example, Bell & Howell’s plan was challenged in the Delaware Court of Chancery in 1983, but the court refused to enjoin (on 48 hours’ notice) the issuance of preferred stock under the plan, noting that it was impossible to sufficiently consider the parties’ arguments, and that the merits would need to be considered at a later time, after the issuance, while recognizing that at that point “it may be difficult to fashion an appropriate remedy.”85 The validity of Bell & Howell’s pill was not further litigated. Having noted that the court’s decision would be “a major factor in determining whether to implement the Plan,”86 the court’s refusal to enjoin the pill paved the way for further adoptions of rights plans.

In February 1985, The Economist helped readers understand takeover defense tactics, describing T. Boone Pickens’s and Carl Icahn’s separate attempts on Phillips Petroleum.

It was in the context of the Lenox takeover fight that the rights plan achieved its notorious nickname, with the Wall Street Journal noting in June 1983 that the strategy being used in Lenox’s takeover battle “is being referred to on Wall Street as ‘the poison-pill defense.’”87 Lipton would later lament the name as “a most unfortunate misnomer. It is neither a pill nor poisonous. It is merely a compact between a company and its shareholders designed to protect against takeover abuses and assure the shareholders of a fair price and fair treatment.”88 Nevertheless, perhaps owing to the evocative language and its increasingly common usage, Lipton frequently embraced the usage of the “poison pill” name, including in the titles of his own memos.89

The validity of Lenox’s and ENSTAR’s pills were likewise never decided on the merits, although in considering Lenox’s pill, the Court of Chancery noted that “the ‘poison pill’ amendments measure, enacted by the Board when ‘takeover’ fever gripped the industry, could be considered legitimate exercises of Board discretion designed to protect the stockholders against a less than arms-length sale.”90 That early reference to the pill as a matter of board discretion would form the precursor to the most important case upholding the validity of the pill, Moran v. Household International, Inc.,91 discussed in the next section.

Takeover Defense Comes To Delaware: Unocal – Moran – Revlon

It was not until 1985 that Lipton’s position on takeover defense and tactics, and the rights plan (or poison pill) of his creation, were directly addressed by the Delaware courts. Then, in the space of nine months, the Delaware Supreme Court issued three opinions that per force took the measure of Lipton’s views, and have long remained the cornerstone of Delaware’s takeover jurisprudence.

Unocal.92 On June 10, 1985, in Unocal Corp. v. Mesa Petroleum Co., 493 A.2d 946 (Del. 1985), the Delaware Supreme Court for the first time considered the proper role of directors of a corporation faced with an unsolicited takeover bid and the nature of judicial review to be employed when that director’s conduct is challenged as a breach of fiduciary duty. The decision came in the context of what the Court called “an issue of first impression in Delaware — the validity of a corporation’s self-tender for its own shares which excludes from participation a stockholder making a hostile tender offer for the company’s stock.”93 Reversing the Court of Chancery, the Court stated:

The factual findings of the Vice Chancellor, fully supported by the record, establish that Unocal’s board, consisting of a majority of independent directors, acted in good faith, and after reasonable investigation found that Mesa’s tender offer was both inadequate and coercive. Under the circumstances the board had both the power and duty to oppose a bid it perceived to be harmful to the corporate enterprise. On this record we are satisfied that the device Unocal adopted is reasonable in relation to the threat posed, and that the board acted in the proper exercise of sound business judgment. We will not substitute our views for those of the board if the latter’s decision can be “attributed to any rational business purpose.”94

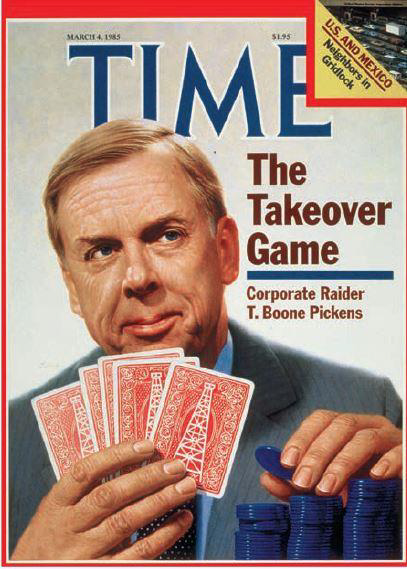

Raider T. Boone Pickens, CEO of Mesa Petroleum, made a bid for Unocal in 1985. The Delaware Supreme Court’s decision on the matter helped cement the legal rationale behind the pill.

The Court’s analysis relied in significant respects on Lipton’s Takeover Bids article and other related writings. Addressing first “the basic issue of the power of a board of directors of a Delaware corporation to adopt a defensive measure of this type,” the Court echoed Lipton’s argument that such power derived from the directors’ power to manage the corporation’s “business and affairs” under DGCL § 141(a), as well as the board’s “fundamental duty and obligation to protect the corporate enterprise, which includes stockholders, from harm reasonably perceived, irrespective of its source.”95 Pointedly rejecting the position of Lipton’s antagonists, the Court declared that “in the broad context of corporate governance, including issues of fundamental corporate change, a board of directors is not a passive instrumentality.”96 And, specifically in this regard, the Court repeated one of Lipton’s key points that under the corporate statute, director action is a “prerequisite to the ultimate disposition of such matters” as mergers, charter amendments, sales of assets and dissolution.97

Turning to the question of judicial review, the Court referenced the “intense debate among practicing members of the bar,” citing to Lipton’s Takeover Bids and the contrary writings of Easterbrook and Fischel.98 As a first principle, the Court held that in responding to a takeover bid, “a board’s duty is no different from any other responsibility it shoulders, and its decisions should be no less entitled to the respect they otherwise would be accorded in the realm of business judgment.”99 That said, the Court identified “an enhanced duty” of “judicial examination at the threshold” owing to the “omnipresent specter that a board may be acting primarily in its own interests.”100 That “inherent conflict,” the Court held, required directors to show that “reasonable grounds for believing that a danger to corporate policy and effectiveness,” and that any defensive measure be “reasonable in relation to the threat posed.”101 Thus, the Court embraced Lipton’s basic views but with an important distinction. It innovated a new intermediate standard of review that was more intensive than the business judgment rule’s bare rationality standard, and that required a showing of reasonable care and loyalty, and a reasonable fit between the threat the corporation faced and the means selected to defend it. But that standard was a manageable one for boards to meet if they used the approach Lipton recommended in Takeover Bids, and was meaningfully less intrusive than “entire fairness” review.

In elaborating on that new intermediate standard of review, the Court noted the important role of independent directors on the target board, a topic Lipton had long highlighted, and indicated that when a majority of independent directors decided to take defensive action, that gave enhanced credibility to the board’s ability to meet its burden of reasonableness under the new test the decision articulated.102 Notably, the Unocal board used techniques Lipton had outlined in Takeover Bids, such as separate meetings of the independent directors, extensive presentations by independent advisors, and truly deliberative meetings, the failure of which had been a principal focus of the Delaware Supreme Court’s decision earlier in the year in Smith v. Van Gorkom, 488 A.2d 858 (Del. 1985). The use of these techniques led to the Supreme Court crediting the Unocal board’s good faith and diligence.

The Court also relied directly on Lipton’s stakeholder position and views on the coerciveness of partial two-tier tender offers, citing again to Takeover Bids and a related paper based on it:

This entails an analysis by the directors of the nature of the takeover bid and its effect on the corporate enterprise. Examples of such concerns may include: inadequacy of the price offered, nature and timing of the offer, questions of illegality, the impact on “constituencies” other than shareholders (i.e., creditors, customers, employees, and perhaps even the community generally), the risk of nonconsummation, and the quality of securities being offered in the exchange. See Lipton and Brownstein, Takeover Responses and Directors’ Responsibilities: An Update, p. 7, ABA National Institute on the Dynamics of Corporate Control (December 8, 1983). While not a controlling factor, it also seems to us that a board may reasonably consider the basic stockholder interests at stake, including those of short term speculators, whose actions may have fueled the coercive aspect of the offer at the expense of the long term investor.11 Here, the threat posed was viewed by the Unocal board as a grossly inadequate two-tier coercive tender offer coupled with the threat of greenmail.

11There has been much debate respecting such stockholder interests. One rather impressive study indicates that the stock of over 50 percent of target companies, who resisted hostile takeovers, later traded at higher market prices than the rejected offer price, or were acquired after the tender offer was defeated by another company at a price higher than the offer price. [Citing Takeover Bids.] Moreover, an update by Kidder Peabody & Company of this study, involving the stock prices of target companies that have defeated hostile tender offers during the period from 1973 to 1982 demonstrates that in a majority of cases the target’s shareholders benefited from the defeat. The stock of 81% of the targets studied has, since the tender offer, sold at prices higher than the tender offer price. When adjusted for the time value of money, the figure is 64%. See Lipton & Brownstein, supra ABA Institute at 10. The thesis being that this strongly supports application of the business judgment rule in response to takeover threats. There is, however, a rather vehement contrary view. See Easterbrook & Fischel, supra 36 Bus. Law. at 1739-45.

Specifically, the Unocal directors had concluded that the value of Unocal was substantially above the $54 per share offered in cash at the front end. Furthermore, they determined that the subordinated securities to be exchanged in Mesa’s announced squeeze out of the remaining shareholders in the “back-end” merger were “junk bonds” worth far less than $54. It is now well recognized that such offers are a classic coercive measure designed to stampede shareholders into tendering at the first tier, even if the price is inadequate, out of fear of what they will receive at the back end of the transaction.103

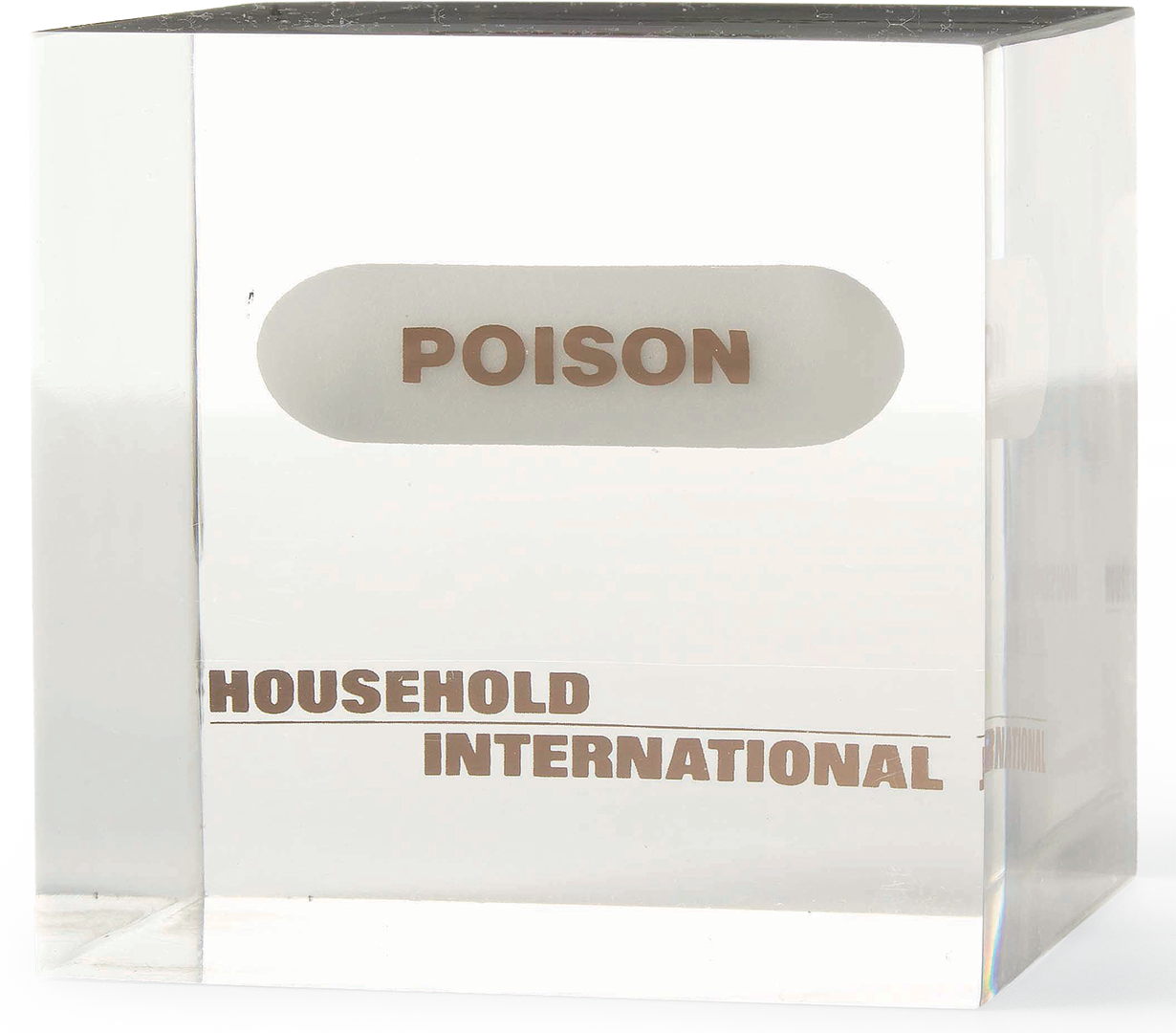

The leading corporate law judge of the era, Chancellor Allen, depicted with the member of the Supreme Court most interested in corporate law in that era, Justice Andrew G.T. Moore, II, in a photo that illustrates the sometimes tense relationship between Chancery and the Supreme Court in this high-stakes era.

At the same time as the decision in Unocal vindicated Lipton’s basic view of the law of takeover defense, it also highlighted a frustration that was largely resolved by his development of the pill. Although the Unocal board prevailed, the tactics it used in many ways mirrored that of the hostile bidder itself (Pickens’ Mesa Petroleum) because Unocal stockholders were presented by management with a coercive, partial self-tender offer into which they had to tender or risk being left on the back end of a more levered company in which debt holders with a high coupon rate had high priority, and a company that was less well positioned to investment in new ventures. Thus, on both a doctrinal and practical level, Lipton’s twin views that boards had the legal authority to defend, but could use a tool that would be less harmful to the target corporations and their stakeholders, were advanced by the doctrinal and practical outcome of Unocal.

Moran.104 Serendipitously, the validity of Lipton’s Rights Plan came before the Delaware Supreme Court while the Unocal case was under submission. The pill case, Moran v. Household International, Inc., 500 A.2d 1346 (Del. 1985), was submitted in the Supreme Court on May 21, 1985 — five days after Unocal was submitted — and decided on November 19, 1985, some five months after the Unocal decision.

This high-stakes drama was unusual in a couple of respects. First, the challenge to the pill was not in the context of a pending bid, but rather in the form of what was essentially an action for a declaratory judgment that Lipton’s creation was invalid in all conceivable circumstances. A director of Household, who was also the chairman of Household’s largest single stockholder (Dyson-Kissner-Moran Corporation) that reportedly had some interest in possibly making a future offer, was Skadden’s client. No bid was pending. The pill that had been adopted was the first generation “flip-over” pill, that entitled the Household stockholders, in the event of a merger with the Rights not having been redeemed by the board of directors, to purchase $200 of the common stock of the tender offeror for $100. Notably, the Rights in the Household pill provided for the stockholders to receive a non-trivial payment for redemption ($.50 per Right) — a feature that would change in later pills so that the price of redemption was essentially costless to the company. Most importantly, the pill had no flip-in feature. Thus, a bidder could acquire control and live with a minority, if it was willing to forego a merger or other consolidation.

Second, Lipton’s longtime friend and the leading lawyer for hostile bidders, Joe Flom and his Skadden firm had helped inspire the litigation, and put a full team into the battle to have the pill declared invalid under Delaware corporate law. Lipton fielded an “A Team” of his own at Wachtell Lipton, led by his fellow founding partner, George A. Katz.

Wachtell Lipton founder George Katz played a leading role in helping Lipton in key takeover battles, and as a close friend and colleague. It was not by coincidence that when the pill’s validity was at issue in Moran, Katz was chosen to lead the Wachtell Lipton team.

Reflecting the high stakes, the trial involved prominent expert witnesses from business and academia testifying about the practical and legal consequences of the pill. For example, to defend the pill, the Wachtell Lipton litigation team put on Jay Higgins, head of the M&A department at Solomon Bros., and Raymond Troubh, a former partner of Lazard Freres with extensive firsthand experience in merger and acquisition deals. To advance its position that the pill was a show-stopper that would improperly interfere with the rights of stockholders under Delaware law, and with their rights under the Williams Act to accept tender offers, Skadden put on Harvard Business School Professor Michael Jensen and University of Michigan Business School Professor Michael Bradley, along with Alan Greenberg, then CEO of Bear Stearns and considered by many to be the dean of arbitrageur practice. The context of the case was helpful to Lipton and his team. Given the prevalence of coercive, two-tiered tender offers and the need of the trial court to consider all the possible circumstances in which the pill could be used, the Skadden team found it more difficult to prove its case because without director action, there was no way to prevent coercion of stockholders by these offers, which were permissible under federal law. Not only that, because there was no pending bid and because Skadden was attacking the validity of the pill in general and not its use in a particular situation, Skadden bore the difficult burden of showing that the pill could not be lawfully used in any circumstance.

In holding for the Household board and refusing to strike down their adoption of the pill, the Court of Chancery pointed to the bidder practices then prevalent, finding that the board had ample basis for considering Household vulnerable to a “two-tier” takeover via that coercive practice in which stockholders were forced to tender lest they be “frozen out” of any premium once the bidder acquired control. The Court of Chancery also rejected Skadden’s arguments that the pill was impermissible because it treated the bidder, as a stockholder, differently from other stockholders, and the Rights were “sham” securities impermissible under the Delaware corporation statute.105

When the decision in Unocal came down, that boded ill for the appeal of that decision. In Unocal, it had been argued that exempting Pickens from the company’s own offer was improperly discriminatory, but the Delaware Supreme Court rejected that argument, citing with some irony to past cases permitting greenmail payments to raiders like Pickens. Thus, the reality that once the flip-over rights were triggered, the rights plan would dilute the acquirer by granting a large amount of equity to all the other stockholders was rendered of little utility to the opponents of the pill.

Unocal presaged the outcome in the Moran appeal in an even clearer way. In Unocal, it had been argued that the board’s defense twisted powers given to them under the Delaware General Corporation Law beyond their intended purpose. The Supreme Court rejected that argument in Unocal, stating: “[O]ur corporate law is not static. It must grow and develop in response to, indeed in anticipation of, evolving concepts and needs.”106 That elemental idea well served the defenders of the pill, who argued for the acceptance of a clearly innovative interpretation of Delaware law in response to the then-prevalent, coercive tactic of the “two-tier” tender offer.

In Moran, one of the principal arguments against the poison pill was that the provisions of Delaware law that authorized boards to issue rights to stockholders was designed to permit the issuance to stockholders of rights to purchase shares of their own corporation and for financing purposes, not to give them “rights” that were only designed to thwart their ability to receive a tender offer. The Supreme Court rejected this argument, noting that the rights issued were authorized by the plain language of the statute, and quoting its recent Unocal decision, that statutes should not be confined in their application, but be applied in accord with their language to address evolving business circumstances.107 In its analysis, the Court thus held that board power to adopt a Rights Plan existed under the Delaware General Corporation Law, including by accepting that the plan was “analogous to ‘anti-destruction’ or ‘anti-dilution’ provisions which are customary features of a wide variety of corporate securities” — the very origin for the idea of the pill that Lipton has often pointed to.108

Moran also applied the new Unocal intermediate standard of review in considering whether Household’s adoption of the pills was, as Chancery had found, a “legitimate exercise of business judgment.”109 In affirming that finding, the Court’s opinion noted Lipton’s role in advising the Household board:

The minutes reflect that Mr. Lipton explained to the Board that his recommendation of the Plan was based on his understanding that the Board was concerned about the increasing frequency of “bust-up” takeovers, the increasing takeover activity in the financial service industry, such as Leucadia’s attempt to take over Arco, and the possible adverse effect this type of activity could have on employees and others concerned with and vital to the continuing successful operation of Household even in the absence of any actual bust-up takeover attempt. Against this factual background, the Plan was approved.110

Responding to the challenge that the Rights Plan “usurped stockholders’ rights to receive trade offers,” the Court — again accepting key parts of Lipton’s pill advocacy — concluded “that the Rights Plan does not prevent stockholders from receiving tender offers” and “that the change of Household’s structure was less than that which results from the implementation of other defensive mechanisms upheld by various courts.” Serendipity again helped Lipton and his pill defenders. In a high-profile situation, Sir James Goldsmith had acquired control of Crown Zellerbach, which also had a flip-over pill. Thus, the Supreme Court found that the flip-over pill was not a “show stopper” but could be gotten “around” by that and other methods by which Household could still be acquired by a hostile bidder (the Court listed tender offers conditioned on redemption of the Rights, tenders with high minimums, soliciting consents or running a proxy contest to remove the board and redeem the pill).111

The odd procedural context also led to another important feature of the Moran decision. In addition to citing the stockholders’ ability to elect a new board that could lift the pill as a way around it, the Court made clear that neither its ruling that the pill was not invalid in all circumstances nor that the pill’s initial adoption by the Household board was proper, gave the Household board a blank check to use that pill indefinitely against a specific future bid. Rather, when that happened the new Unocal standard would be applied to the directors’ decision to whether to redeem (or “pull”) the pill in the heat of an actual bid with specific terms:

When the Household Board of Directors is faced with a tender offer and a request to redeem the Rights, they will not be able to arbitrarily reject the offer. They will be held to the same fiduciary standards any other board of directors would be held to in deciding to adopt a defensive mechanism, the same standard as they were held to in originally approving the Rights Plan. See Unocal, 493 A.2d at 954–55, 958.

The Rights Plan will result in no more of a structural change than any other defensive mechanism adopted by a board of directors. The Rights Plan does not destroy the assets of the corporation. The implementation of the Plan neither results in any outflow of money from the corporation nor impairs its financial flexibility. It does not dilute earnings per share and does not have any adverse tax consequences for the corporation or its stockholders. The Plan has not adversely affected the market price of Household’s stock.

Comparing the Rights Plan with other defensive mechanisms, it does less harm to the value structure of the corporation than do the other mechanisms. . . . .

There is little change in the governance structure as a result of the adoption of the Rights Plan. The Board does not now have unfettered discretion in refusing to redeem the Rights. The Board has no more discretion in refusing to redeem the Rights than it does in enacting any defensive mechanism. . . . .

We conclude that there was sufficient evidence at trial to support the Vice-Chancellor’s finding that the effect upon proxy contests will be minimal. Evidence at trial established that many proxy contests are won with an insurgent ownership of less than 20%, and that very large holdings are no guarantee of success. There was also testimony that the key variable in proxy contest success in the merit of an insurgent’s issues, not the size of his holdings. . . . .

The Directors adopted the Plan in the good faith belief that it was necessary to protect Household from coercive acquisition techniques. The Board was informed as to the details of the Plan. In addition, Household has demonstrated that the Plan is reasonable in relation to the threat posed. Appellants, on the other hand, have failed to convince us that the Directors breached any fiduciary duty in their adoption of the Rights Plan.

While we conclude for present purposes that the Household Directors are protected by the business judgment rule, that does not end the matter. The ultimate response to an actual takeover bid must be judged by the Directors’ actions at that time, and nothing we say here relieves them of their basic fundamental duties to the corporation and its stockholders. [Citations omitted.] Their use of the Plan will be evaluated when and if the issue arises.112

Delaware’s validation of the Rights Plan as a legitimate defensive mechanism was, like Unocal, an emphatic validation of the approach to takeovers advocated by Lipton. Two days after the Supreme Court’s decision, Lipton reaffirmed that “[a] Rights Plan is legal. A Rights Plan is within the business judgment of the board of directors.”113 Once again, he reminded clients that a “Rights Plan should be adopted before a company becomes a target.”114

At the same time, Lipton attacked the Wall Street Journal’s anti-Moran editorial (“Et Tu, Delaware”),115 and noting that “takeover entrepreneurs and speculators hate Rights Plans and are continuing their campaign to outlaw them”:

While Rights Plans do not prevent all take overs, they do protect against abusive takeover tactics and they do deter bust-up, bootstrap, two-tier, junk bond takeovers. Naturally those who profit from these takeovers at the expense of American business, workers and communities, and whose wildly speculative activities threaten our entire economic system, oppose anything that restricts their activities. There is no stronger argument for implementing a Rights Plan now.116

Revlon.117 The third of the 1985-86 trilogy in Delaware turned primarily not on a takeover defense in isolation, but a “lock-up option” agreed to by a target board of directors to secure a higher-priced LBO takeover bid to block an initial hostile suitor. In Revlon, Inc. v. MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings, Inc., 506 A.2d 173 (Del. 1986), the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed an injunction against a “crown jewel” lock-up option granted by the Revlon board to Forstmann Little & Co., the financial sponsor of an LBO, as part of the company’s response to the unsolicited efforts of a Ronald Perelman company (Pantry Pride, Inc.) to acquire Revlon.

[I]t would be very helpful if statutes permitting directors to consider constituencies other than shareholders were adopted in Delaware and the other states.

Previously, in response to Perelman’s hostile bid, the Revlon board had approved — on Lipton’s advice — a Note Purchase Rights Plan under which Revlon stockholders received as a dividend one Note Purchase Right to acquire a $65 principal Revlon one-year note at 12% interest in exchange for one common share, triggered by anyone acquiring 20% or more of Revlon’s shares unless that person acquired all shares at $65 cash per share or more; as in a pill, the Rights were not available to the acquiror and could be redeemed by the board prior to a 20% triggering event. In addition, Revlon had responded to Perelman’s $47.50 per share offer with a self-tender for up to 10 million shares, in exchange for $47.50 principal Notes and preferred stock — which was fully accepted by the Revlon stockholders. After further bidding by Perelman, the Revlon board agreed to a $56 per share cash deal with Forstmann, with management participating in the new company, and Forstmann assuming Revlon’s debt incurred by the issuance of the Notes; as part of the deal, Revlon would redeem the Rights. After Perelman raised to $56.25/share conditioned on the board’s removal of the Rights (and announced that he would top any Forstmann offer by a slightly higher one), Forstmann countered with a $57.25 per share offer, conditioned on receiving a lock-up option to acquire Revlon’s vision and health divisions for $525 million — which was $100.175 million below value; management would not participate, and Forstmann committed to support the par value of the Notes, which had fallen in the market, by an exchange of new notes. The Revlon board agreed to the option, because the Forstmann bid was higher than Perelman’s and it protected the Noteholders (who had only just recently been solely stockholders of Revlon and had received the Notes in exchange for some of their Revlon shares as part of a defensive self-tender). In response, Perelman raised to $58/share conditioned on nullification of the Rights and an injunction against the Forstmann lock-up.

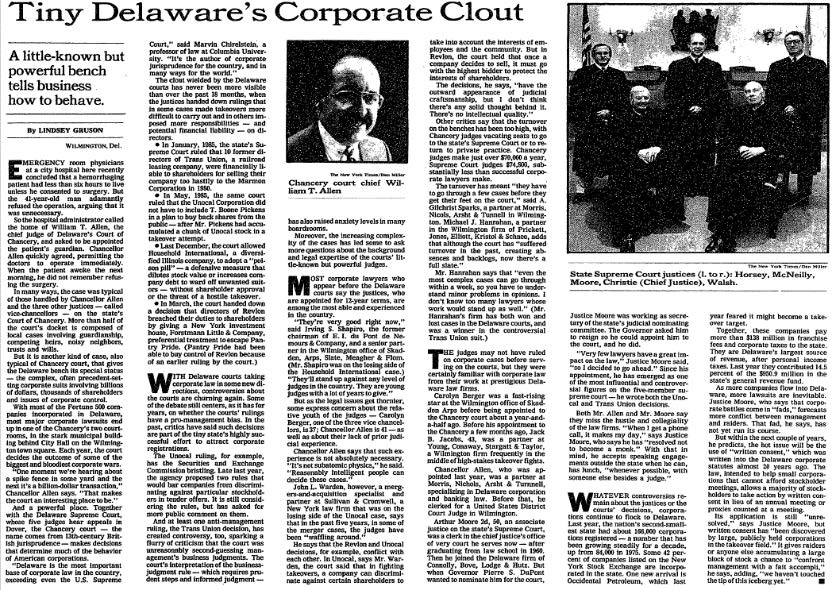

The New York Times: Tiny Delaware’s Corporate Clout June 1, 1986

In its opinion, the Supreme Court framed the issue before it as requiring decision “for the first time the extent to which a corporation may consider the impact of a takeover threat on constituencies other than shareholders,” citing Unocal.118 The Court approved the Revlon board’s adoption of the Note Purchase Rights Plan as “protect[ing] the shareholders from a hostile takeover at a price below the company’s intrinsic value [at that point, Perelman’s $45 bid], while retaining sufficient flexibility to address any proposal deemed to be in the stockholders’ best interests.”119 The Court, however, held that the “usefulness” of the Rights had become moot once the Revlon board agreed to their redemption in favor of the Forstmann white-knight transaction, thereby “moot[ing] any question of their propriety under Moran or Unocal.”120 The Court also approved Revlon’s defensive self-tender in which its board encouraged stockholders to exchange some of their shares of Revlon for the Notes. Nonetheless, the Court held that the Revlon board’s responsibilities changed once it authorized the negotiation of the sale of the company to Forstmann:

The Revlon board’s authorization permitting management to negotiate a merger or buyout with a third party was a recognition that the company was for sale. The duty of the board had thus changed from the preservation of Revlon as a corporate entity to the maximization of the company’s value at a sale for the stockholders’ benefit. This significantly altered the board’s responsibilities under the Unocal standards. It no longer faced threats to corporate policy and effectiveness, or to the stockholders’ interests, from a grossly inadequate bid. The whole question of defensive measures became moot. The directors’ role changed from defenders of the corporate bastion to auctioneers charged with getting the best price for the stockholders at a sale of the company.121

Going further, the Court rejected the Revlon board’s position that it was entitled to protect the Noteholders — as only the Forstmann bid then did — under the constituency concept of the Unocal opinion:

Such a focus was inconsistent with the changed concept of the directors’ responsibilities at this stage of the developments. The impending waiver of the Notes covenants had caused the value of the Notes to fall, and the board was aware of the noteholders’ ire as well as their subsequent threats of suit. The directors thus made support of the Notes an integral part of the company’s dealings with Forstmann, even though their primary responsibility at this stage was to the equity owners.

The original threat posed by Pantry Pride — the break-up of the company — had become a reality which even the directors embraced. Selective dealing to fend off a hostile but determined bidder was no longer a proper objective. Instead, obtaining the highest price for the benefit of the stockholders should have been the central theme guiding director action. Thus, the Revlon board could not make the requisite showing of good faith by preferring the noteholders and ignoring its duty of loyalty to the shareholders. The rights of the former already were fixed by contract. [Citations omitted.] The noteholders required no further protection, and when the Revlon board entered into an auction-ending lock-up agreement with Forstmann on the basis of impermissible considerations at the expense of the shareholders, the directors breached their primary duty of loyalty.The Revlon board argued that it acted in good faith in protecting the noteholders because Unocal permits consideration of other corporate constituencies. Although such considerations may be permissible, there are fundamental limitations upon that prerogative. A board may have regard for various constituencies in discharging its responsibilities, provided there are rationally related benefits accruing to the stockholders. Unocal, 493 A.2d at 955. However, such concern for non-stockholder interests is inappropriate when an auction among active bidders is in progress, and the object no longer is to protect or maintain the corporate enterprise but to sell it to the highest bidder.122

The Supreme Court’s decision that the Noteholders’ interests could not be considered was important and striking. Not only was it directly in conflict with its statement in Unocal, the ruling addressed Noteholders who were also likely still Revlon stockholders and had received their Notes for some of their shares just weeks before at the urging of the Revlon board and with the promise that the independent directors would protect their value. Thus, the best deal for them would depend on the combined value of what they received for their stock and their Notes. Put simply, no group of stakeholders could be closer to being stockholders than the Revlon Noteholders. But, when Revlon’s lawyer on appeal raised this argument at the beginning of his presentation, citing to Unocal, the Justice who authored Unocal cut him off and said that Unocal had not meant what it said in its dictum about other constituencies.123 In its decision, the Supreme Court seemed most disturbed by Revlon’s refusal to put Perelman on a level playing field with Forstmann and it is impossible to determine whether if it had given Perelman a chance to bid on equal terms so long as he provided comparable note protection, how the case and contest itself might have come out. But, as a matter of reality and doctrine, Revlon resulted in a holding that sharply limited the ability of boards to protect stakeholders once they had decided to sell the company.

Revlon thus opened the door to eschewing the Lipton-style consideration of corporate constituencies that some had thought to be a centerpiece of Unocal — at least once the target board itself had decided to sell the company, and thereby moved from “defenders of the corporate bastion to auctioneers charged with getting the best price for the stockholders at a sale of the company.”124 The nature of that new role, and the question of what triggers it, became the centerpiece of continued debate and litigation in the years, and decades, that followed, and that is still central in the current debates over corporate purpose.

Even though the Revlon opinion did not pull back on the propriety of takeover defenses (and indeed approved the Revlon board’s initial, aggressive defensive tactics), Lipton viewed the opinion as creating “confusion” and as seeming “to retreat somewhat” from Unocal; he urged that “it would be very helpful if statutes permitting directors to consider constituencies other than shareholders were adopted in Delaware and the other states.”125 Lipton then fueled that movement, in which a majority of American states, but not Delaware, adopted statutes that rejected Revlon and allowed boards to consider all stakeholders when addressing takeovers and M&A more generally.126

As to the injunction against the Forstmann lock-up option, Lipton concluded that “it is difficult to draw clear guidelines” about lock-ups, and that although Revlon said that “not all lockups are illegal,” “the trend in the courts is unfavorable.”127 A few years later, Lipton was quoted as labeling the Revlon decision “a horrendous mistake” that was “dead wrong to second-guess a competent board of directors.”128 But, coming out of Revlon, the most immediate challenge to the cause of takeover defense championed by Lipton was how the nascent Unocal standard would be applied in cases before the Court of Chancery, especially as bidders were beginning to present all-shares, all-cash bids that could not readily be characterized as structurally coercive. Unocal itself signaled more deference to boards than Revlon did, and Moran’s admonition that boards’ use of pills would be reviewed in light of the specific bid presented set the stage for another period in which Lipton’s perspective on takeovers would be tested in the market and court.

The Validity of Flip-In Pills Is Tested and Established

In June 1986, Lipton wrote that “the poison pill has been adopted by about 200 major corporations and has proved to be effective.”129 By October, “[w]ell over 300 companies have adopted rights plans.”130 And in his memo commemorating the first anniversary of Household, Lipton noted that 29% of Fortune 500 companies and 36% of Fortune 200 companies had adopted rights plans.131 By July 1987, the rights plan had been adopted by over 400 companies.132 And by November 1988, that figure had grown to more than 800.133

By the end of the decade, crafty evolutions of the pill were required to fend off increasingly sophisticated attacks.

Although Lipton had staked his own reputation on the validity of the flip-over rights plan, he continued to strike a cautious tone as to its more aggressive sibling — a pill that combined a flip-over provision as in Lipton’s original pill with a more assertive flip-in provision. Flip-in provisions “give the shareholders the right to buy additional shares at a bargain price whenever a raider crosses a threshold that varies from plan to plan.”134 Because of the substantial dilution that would be imposed upon the raider that crosses the plan’s threshold, Lipton saw a flip-in as “a major deterrent to open-market accumulations, partial tender offers and tenders where the raider would purchase 50% or more and not undertake a second-step merger and thereby avoid triggering the basic flip-over provision.”135 Lipton acknowledged that “including a flip-in provision would, of course, strengthen our rights plan,” but refrained from doing so “out of fear that a court would find that it was illegal and that it tainted the validity of the whole rights plan.” 136

In Europe and other regions of the world, acquirers would obtain control of public companies and not merge out the remaining stockholders. American takeover bidders began to adapt to this approach in the face of the flip-over pill. For that reason, many companies and other law firms began adopting versions of the pill with a flip-in feature that would be triggered by any acquisition of shares above a certain percentage, such as 15 percent, and could thus block a change in control from happening at all. Lipton was aware of these developments, but was conservative in moving toward the flip-in pill. While remaining focused on curbing not takeovers, but takeover abuses, Lipton began to endorse some measured provisions that had flip-in aspects but would be triggered only in the case of potential abuse and not simply because a bidder crossed a certain ownership threshold without board approval (i.e., a “status flip-in”):

The Rights Plan also provides protection against self-dealing transactions by a 20% shareholder. If a 20% shareholder were to effect an acquisition of the issuing company by means of a reverse merger in which the company and its stock survive, or engage in certain self-dealing transactions with the issuing company (such as sales of assets to the company or obtaining certain financial benefits from the company), each right not owned by such shareholder would become exercisable for that number of shares of the issuing company’s common stock which at the time of such transaction would have a market value of two times the exercise price of the right. Thus, although an acquiror may acquire a controlling block without effecting a second step, he will be penalized if he uses his control position to treat the issuing company’s shareholders unfairly.137

Consistent with his focus on abuses not blocking all changes of control, Lipton reiterated that this self-dealing-triggered flip-in provision “does not prevent takeovers” and “has no effect on an acquiror who is willing to acquire control and not obtain 100% ownership through a merger until after the rights have expired provided that the acquiror does not engage in self-dealing transactions with the issuing company.”138

Lipton’s early caution regarding flip-in provisions turned out to be warranted. As the judicial waters were tested, courts distinguished flip-in provisions from flip-over provisions, finding in certain instances that flip-in provisions were invalid. Even flip-in-provisions triggered only by self-dealing, such as the one endorsed by Lipton, were invalidated in the NL Industries case, in which the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York found the flip-in provision invalid under New Jersey law:

[T]he rights plan, and in particular the flip-in provision of that plan . . . is ultra vires as a matter of New Jersey Business Corporation law. The flip-in effects a discrimination among shareholders of the same class or series. Under the plan the voting rights and the equity of an acquiring shareholder are diluted upon a triggering event. . . . New Jersey law clearly does not allow discrimination among shareholders of the same class and series.139

The court expressly distinguished Household on the ground that Household contained “only a flip-over,” and because the Court in Household found that the rights plan in question did not impede the tender offer process, while the court found that the plan in NL Industries “does prevent stockholders from receiving tender offers.”140

Having endorsed the validity of flip-in provisions triggered only upon instances of self-dealing, Lipton responded to the NL decision in no uncertain terms:

[W]e believe that the NL decision is wrong. We believe it is an erroneous interpretation of New Jersey corporate law and an erroneous view of the effect of Rights Plans. . . . We continue to believe that Rights Plans of the Household type (flip-over) and NL type (flip-over and flip-in for protection against self-dealing) are valid and legal and are highly desirable in this era of coercive, bust-up, junk-bond, boot-strap takeovers.141

Despite NL Industries, Lipton remained optimistic regarding stockholder rights plans generally, writing that occasional adverse rulings “will not stop the movement” toward rights plans. “At most, they will eliminate the flip-in provisions contained in some plans and bring home the message that the best time to adopt a plan is before an attack.”142 Lipton viewed the challenges to rights plans as “demonstrat[ing] that Rights Plans in fact are a very effective counter to today’s coercive takeover techniques”143 that “have proved to be very effective in curbing abusive takeover tactics and increasing the negotiating strength of the target’s board.”144 Confident that judicial momentum would continue trending toward Delaware’s rulings, Lipton wrote: “We continue to believe that the decisions of the Delaware Supreme [C]ourt in the Household and Revlon cases are the correct view as to Rights Plans and we continue to recommend the adoption of Rights Plans.”145

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit’s 1986 opinion in CTS,146 authored by Judge, and former Chicago Law School Professor, Richard Posner, marked a milestone in the endorsement of the validity of the flip-in rights plan. Lipton viewed the decision as having “great significance, particularly in light of Judge Posner’s express distaste for poison pills.”147 Judge Posner’s background in law and economics deriving from his important and prominent work148 while at the University of Chicago (alongside takeover defense opponents Frank Easterbrook (later a Judge of the 7th Circuit himself) and Dan Fischel) made the victory for the rights plan especially satisfying for Lipton. Stemming back to the intellectual debate over Takeover Bids, Lipton had long observed that the stock market-oriented Chicago school was antithetical to takeover defenses. To Lipton, Chicago school economists, “[w]ith their efficient market theories, they point to stock markets’ favorable reactions to takeovers as proof that takeovers are good for the economy,”149 while the deleterious effects of takeovers “are well-nigh invisible to those economists of the Chicago school (and their special friends among law professors) who are in love with takeovers.”150 Thus, as Lipton wrote, “[t]he Pill is an anathema to the Chicago School,”151 making Judge Posner’s decision to uphold the district court’s refusal to enjoin the rights plan all the more important. Lipton considered the opinion “an extremely important reaffirmation of the basic legality of poison pills established by the Supreme Court of Delaware” and hoped that it would be “instructive to other federal courts which have taken a more restrictive view.”152 That said, it should be noted that Judge Posner’s view of rights plans remained lukewarm at best. As the opinion notes, CTS’s first attempt at creating a rights plan that could withstand enhanced scrutiny under Unocal “clearly flunked the test,” and in upholding its second rights plan, Judge Posner expressed his continued “skepticism concerning the propriety of poison pills.”153

Though a less noteworthy decision, the federal district court decision in Gelco Corp. v. Coniston Partners likewise allowed Lipton to applaud the court’s validation of “both a flip-over and a 20% flip-in” as “a correct statement of the law with respect to poison pills,” noting that the court “specifically rejected the questionable reading of New Jersey law in the NL case.”154 Thus, a year after Household and after a number of subsequent court victories, Lipton’s assessment of the judicial landscape was optimistic, even with respect to flip-in provisions:

On balance, it appears that most courts will follow Household and today there is relatively little doubt as to legality, even with respect to the flip-in provision that has caused the most difficulty in the courts.155

Institutional Investors and the Rights Plan

Outside the courtroom, the most significant debate over the rights plan occurred between Lipton and institutional investors, which had risen to power and become key participants in the 1980s takeover era. Lipton’s engagement with the rising influence of institutional investors was initiated in his Takeover Bids article, and would continue, to this date, to be a principal focus of his concerns over whether the American corporate governance system is appropriately oriented toward sustainable wealth creation and the fair treatment of employees and other company stakeholders.

In the 1980s, Lipton viewed institutional investors as responsible for much of the focus on short-term financial results that had fueled the financialization of takeovers. Lipton viewed the nation as having entered the “the age of finance corporatism, which is dominated by the institutional investor and the professional investment manager. The existence of large pools of capital managed to maximize short-term performance has fueled a wave of highly leveraged takeovers that threatens a variety of constituencies, including shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, and communities, as well as the economy as a whole.”156 Of institutional investors, Lipton observed: “Never in the history of our modern economic development has so much economic power been held by so few.”157

Never in the history of our modern economic development has so much economic power been held by so few.

Institutional investors’ focus on short-term financial results at the expense of society was antithetical to Lipton’s beliefs, arising from his studies under Adolph Berle, in the “enterprise theory — the concept that corporations should be managed not just in the interests of the shareholders, but in the interests of the enterprise as a whole, which includes, of course, the employees, customers, suppliers, and the community in which a corporation lives.”158 As Lipton observed, “the shareholders-only view ignores the reality that other constituencies both share the risk and are vital to the success of corporate activity.”159 Lipton wrote that “management historically pursued socially beneficial objectives such as expanding the enterprise, improving productivity, and cultivating planning, research, and development. In contrast, the new control persons — the institutional investors — share none of these social goals.”160 As to institutional investors’ support for takeovers, Lipton did not mince words in sounding the alarm, writing that institutional investors “are using their power to force corporations to focus on short-term profits rather than long-term growth” and “forcing massive reductions in research and development and capital investment.”161 As a result, “institutional investors are not just insisting on a takeover premium when a company is put in play, they are actively promoting takeovers.”162 He regarded institutional investors as agents that “have gained control of virtually every major company” and “show no restraint and no regard for the public good,” and cautioned that they “must be policed. . . . We must mandate that they be long-term investors not short-term speculators and promoters of takeovers.”163

[T]he shareholders-only view ignores the reality that other constituencies both share the risk and are vital to the success of corporate activity.

As to the deteriorating relationship between management and institutional investors, Lipton’s view was bleak:

Despite their protestations against the charge that they sell out good management that has good long-term prospects, institutional investors continue to do so and continue to discourage the long-term investments that are essential for American business to remain competitive in the world market.164

Lipton described the susceptibility of management to takeovers resulting from the pressures imposed by institutional investors:

American management has lost confidence in institutional investors. Management views institutional investors as effectively controlling the price of securities through their market activity with no regard for the long term needs of corporations and their managements. Long term profitability may require measures that will reduce earnings in the short term, but institutional investors are too concerned with quarter-to-quarter performance of their managed assets . . . This depresses the value of a farsighted company’s securities and makes the company an attractive takeover target. Thus, management may be forced to choose between prudent management and avoiding a takeover battle.165

Underlying the short-term pressures imposed by institutional investors lay an important question — why were these investors so susceptible to the temptations of short-termism and takeovers? Quoting Warren Buffett, Lipton noted the irony that institutional investors, “which should have the longest investment perspective, have been transformed by the competitive race on Wall Street into some of the most speculative players around.”166 As Lipton noted, “competitive pressures also drove many of the fiduciaries that hold most of the country’s private capital, including pension funds, into the [takeover] game.”167

Lipton observed that these competitive pressures were driven by the short-term pressures placed on fund managers, whose interests were not necessarily aligned with the institutional investor, much less the companies in which they were invested:

Institutional investors also exacerbate the situation by preferring short-term gains to long-term growth. Institutions will accept any premium over the current stock market price rather than hold a portfolio investment for appreciation. Competitive necessity mandates this investment policy: To survive, institutional investment managers must perform better than the market as a whole. Their profession forces investment managers to not only accept usual takeover premiums but also to join ranks with takeover entrepreneurs to pressure companies into new deals that will produce a premium over the current market. Takeover entrepreneurs have gained the active support of major institutional investors.168

Despite his pessimistic appraisal of the short-term philosophy of institutional investors, Lipton recognized that, if their incentive problems could be corrected, the rising prominence of institutional investors could present “a unique opportunity to bridge the corporate governance gap between ownership and control”:

Most corporations now have shareholders who are sufficiently large to have a real stake in corporate governance and sufficiently professional to possess the skills necessary to bring their influence to bear. As such, shareholder democracy, which heretofore has been viewed as inherently unworkable because small, diversified shareholders generally lack the interest to become involved in corporate governance, can become a reality.

Self-interest motivates institutional investors to actively seek — including by promoting or encouraging hostile takeovers — short-term investment profits. The full benefits of shareholder democracy cannot be achieved until the short-term focus of investment managers and the competitive pressures they face are rectified.169

If these fund managers’ incentive problems could be cured, Lipton saw institutional investors as potentially being recalibrated “to provide ‘patient’ capital to permit management to make the long-term investments that are essential for a strong economy. We must develop long-term relationships between companies and their institutional investors, with the investors being committed to support management’s long-term business plans.”170 Doing so would allow institutional investors to support long-term economic growth:

Institutions will best serve their beneficiaries by shifting their focus from short-term trading strategies to policies that encourage corporations to seek long-term growth. This is the only way in which all investors and citizens benefit.

As the total assets under control of institutional investors become larger, their returns must tend towards the market averages by default if not by design. Their future is tied less to a selective portfolio and more to the general economic health of the country. From the standpoint of the market as a whole, stock investing is a zero sum game. Institutions will best serve their beneficiaries by shifting their focus from short-term trading strategies to policies that encourage corporations to seek long-term growth. This is the only way in which all investors and citizens benefit.171

Lipton advocated for solving the institutional incentives problem by encouraging long-term investment through “a tax on institutional investors which takes away all profit on stock held less than one year and most of the profit on stock held less than five years.”172 But although he noted that “the need for legislation is clear,” Lipton recognized that congressional action and tax policy change was not likely, and therefore reiterated that “it is essential that the poison pill — which is the only effective brake on the takeover frenzy — be sustained.”173 It is against this backdrop that institutional investors mounted their campaigns against the rights plan.

The Anti-Pill Campaign

Having largely failed in the courts, the opponents of the rights plan sought to “destroy its effectiveness by proposing sponsoring restrictive SEC rules and presenting proxy statement proposals to subject the Pill to a form of shareholder referendum.”174 Institutional investors were leaders in those attacks. Lipton observed that “institutional investors are joining with corporate raiders to attempt to eliminate defenses against takeover abuses.”175 The aforementioned incentive problems were acutely displayed when institutional investors attacked the stockholder rights plan:

In evaluating these attacks, the self-interest of the managers of these institutions should be noted. They are not investors. They are speculators. They are compensated on the basis of how much quick profit they produce each quarter. They do not invest. They buy and sell. They do not have any long-term interest in the companies whose securities they trade in. . . . They are self-interested promoters of takeovers for their own benefit. They are fueling the takeover frenzy. They encourage raiders, buy billions of dollars of junk bonds to finance bust-up takeovers and act in concert to defeat efforts to protect against takeover abuses.176

Lipton provided companies with a model response to requests to include a shareholder referendum on rights plans at the annual meeting. That model response featured much of Lipton’s cautionary language concerning takeover activities, noting that “bidders have engaged in abusive tactics” and have “little or no regard for the interests of the stockholders of the target company. . . . Our Rights Plan helps to level the playing field between the Company and such bidders.”177 In keeping with his message that rights plans allow for negotiation of superior offers, and do not prevent takeovers outright, Lipton wrote that the rights plan will “allow the board to perform its traditional role of responding to, and negotiating with, a prospective acquiror on behalf of the Company and its diverse body of stockholders.”178 Lipton’s model response reminded stockholders that “[t]he Rights Plan does not prevent the making of an acquisition proposal or the acceptance of an acquisition proposal that the Board finds to be in the interests of stockholders.”179 And in all events, “[i]n determining whether to redeem our Rights Plan in the context of a specific proposal, your Board has an obligation to meet its fiduciary duties and exercise its business judgment.”180

As Lipton observed: “One manifestation of increased activism on the part of institutional investors has been the formation of institutional investor organizations to oppose takeover defenses.”181 One such manifestation was the Council of Institutional Investors, which led a widespread anti-rights plan campaign, supported by the California Public Employees Retirement System and the College Retirement Equity Fund. Of the Council of Institutional Investors, Lipton observed that it “was formed for the stated purpose of getting involved in corporate governance,” yet its endeavors resulted in causing companies to enter into leveraged recapitalizations and focused on attacking defenses against abusive takeover tactics, including the poison pill, and to oppose takeover reform. “In other words, in the guise of a program to improve corporate governance the Council and its members are attempting to determine the outcome of takeover battles and to exercise control over the major American business corporations.”182

In January 1985, the New York Times Magazine ran this article on the “national scandal” of junk-bond takeovers, quoting Marty Lipton.

In 1987, Lipton was invited by Penn ILE Director Professor Michael Wachter and Dean Robert Mundheim to give one of the ILE’s first lectures, which became the basis for an important article published by the Penn Law Review.

This proxy campaign played out in both 1987 and 1988 annual meeting seasons. Lipton followed the campaign closely and updated clients on the “score” as it unfolded, as the referendum was an important indicator of whether the poison pill had reached acceptance not only by the courts, but by stockholders. Lipton warned:

By their campaign against the poison pill, [College Retirement Equity Fund] and the California Retirement System are demonstrating that their self-interest comes before the public interest. If a large number of institutional investors join in this campaign, it will be clear that we cannot rely on self-restraint in the exercise of their power over American corporations and that corrective legislation is the only solution.183

Institutional investors’ resolutions to abolish rights plans were largely voted down in 1987, marking a victory for the rights plan in the court of public opinion. Stockholders of International Paper Co. rejected an anti-right plan resolution, with less than 20% of shares voting in favor, which Lipton noted was a demonstration of “what can be accomplished when corporate management takes the opportunity to present its case to the shareholders.”184 That was the first of many victories for the rights plan in the 1987 proxy season. In the end, Lipton counted a total of 31 companies targeted with anti-rights plan campaigns — not one was successful. As Lipton thus reported, “the Council of Institutional Investors has suffered a stunning defeat in its proxy campaign against the poison pill.”185

In the 1988 annual meeting season, institutional investors returned with another campaign against the rights plan. Lipton predicted that the second generation pill’s inclusion of a stockholder vote (as discussed below) would “enable the large number of pension fund managers who do recognize the dangers of the junk-bond, bust-up takeover frenzy, to vote against the anti-pill resolution.”186 Thus, Lipton began to bolster the second generation rights plan against the next proxy season and against the institutional investors who had “become activists in opposing takeover defenses, voting for corporate raiders in proxy fights and forcing companies to auction themselves to the high bidder.”187 Once again, the institutional investors’ campaigns failed at the ballot box, a result that Lipton attributed to “shareholders recogniz[ing] that the pill is an important protection against abusive takeover tactics.”188 Thus, despite what Lipton characterized as an “intensified anti-pill campaign by CREF, Calpers and their cohorts,”189 a study of the 1988 proxy season found that “voting statistics do not reveal a trend of growing shareholder support for these proposals.”190 Lipton celebrated this result, noting that “despite great effort and special targeting this year, the opponents of Rights Plans failed to achieve greater support this year than they did last year.”191

As time would tell, however, these initial institutional investor attempts to reduce the prevalence of poison pills were but the first wave of such efforts in coming decades.

In the Wake of CTS, Lipton Embraces the Flip-In and Recommends It to Clients

With the rights plan having proved successful both in the courts and at annual meetings, Lipton wrote a memo in July 1987 that introduced a new and more powerful “second-generation” rights plan. Lipton surveyed the effects of and challenges to pills over the previous years, noting that it “has proved to be the most effective protection against abusive takeover tactics,” “has been upheld by most courts that have considered it,” and “has been adopted by over 400 companies.”192 At the same time, Lipton noted that the takeover frenzy had continued, with a litany of takeover abuses from the corporate raider’s “extensive arsenal of powerful takeover weapons,” including, among other abuses, the raider’s ability to “ignore moral obligations to employees, customers, suppliers and communities and bust up a target,” and to “take over a target through a creeping or partial tender offer and then take advantage of the public minority shareholders through self-dealing and conflict transactions,” to “mobilize institutional shareholders to attack any attempt by a target to defeat a takeover and remain an independent company,” and to “usurp the traditional functions of a board of directors to act and negotiate on behalf of the shareholders in a merger.”193 In other words, despite the initial success of the first-generation rights plan, takeover proponents continued to threaten both the enterprise theory of the corporation and the model of board-centric determinism Lipton endorsed in Takeover Bids.

Recognizing both the success of the original pill and the continued effectiveness of the weapons of hostile acquirors, Lipton proposed that “this is clearly an appropriate time to reexamine the pill.” In his second-generation rights plan, Lipton finally advocated for “a flip-in at the 20% acquisition threshold,”194 whether or not there was a threat of self-dealing. That provision would thereby “give[] shareholders of the target, other than the raider, the right to cause unacceptable dilution of the raider’s holdings in the target.”195 It would prevent raiders from acquiring a controlling position through open market purchases, regardless of their subsequent intentions, and would protect shareholders from the possibility that a raider would “avoid[] the effect of the flip-over by not doing a second-step merger after acquiring control.”196

Cognizant of the potential for judicial skepticism over such a potent flip-in provision, and in order to maintain a balance between preventing takeover abuses and allowing shareholders to consider acquisition proposals, Lipton tempered the new proposal by “providing for a shareholder vote if a non-abusive takeover is proposed.”197 The second-generation pill would include a new provision:

[I]f a bidder (who does not hold more than 1% of the shares of the company and therefore is not a greenmailer or a free rider seeking to profit by putting the company in play) proposes to acquire all of the shares of the company for cash at a fair price and has financing or financing commitments, then the company will, if requested by the bidder, hold a special shareholder meeting to vote on a resolution requesting the board of directors to accept the bidder’s proposal. A prospective bidder who holds more than 1% could not avail itself of this provision unless it sold down to 1% before making the request. The bidder would have to furnish an investment banker’s opinion addressed to the shareholders of the company that the price proposed by the bidder is fair.198